A Depression with Chinese Characteristics

Welcome to the Ugly Deleveraging

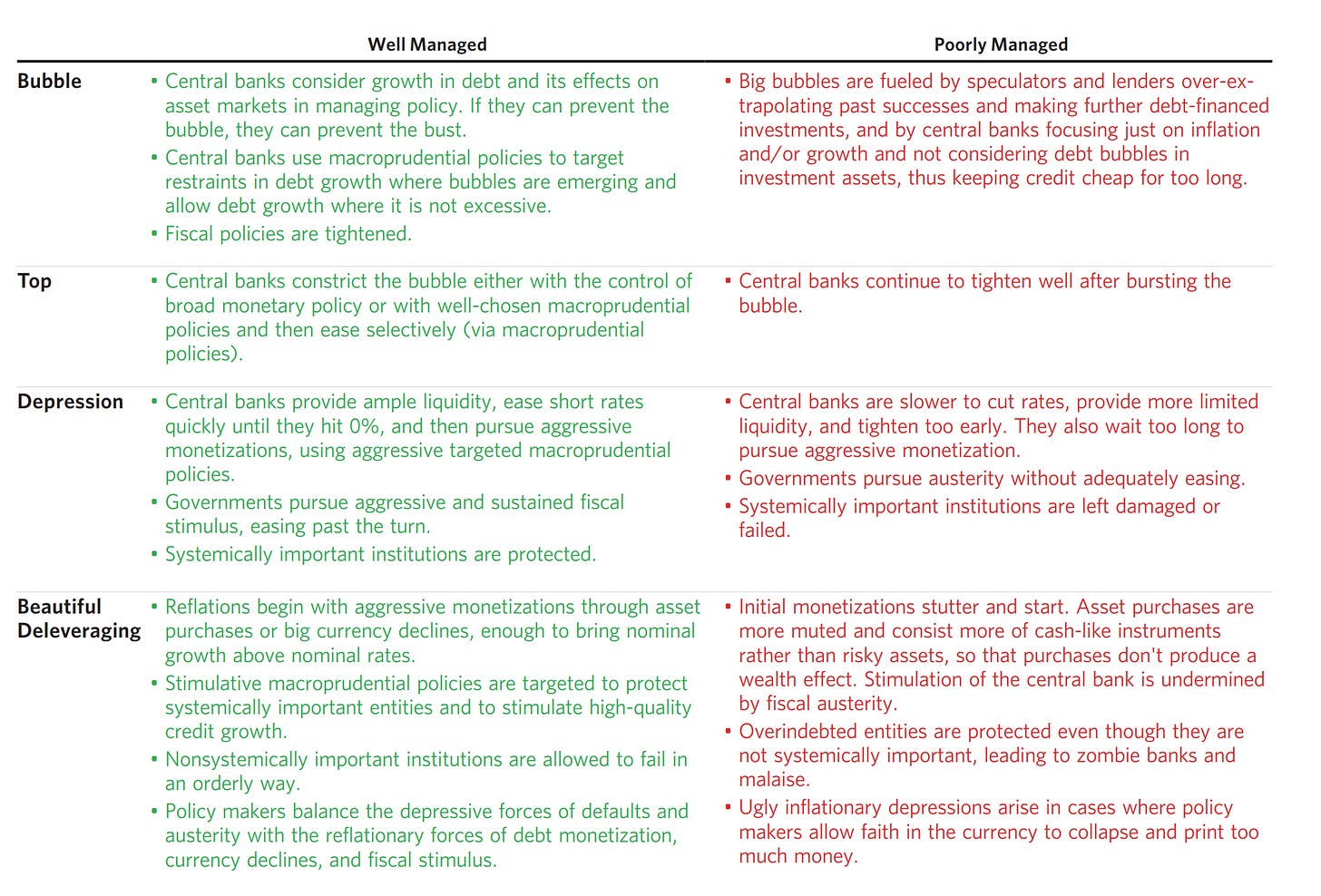

Almost a year ago, my former boss and mentor Ray Dalio put out an article called “China Needs to Engineer a Beautiful Deleveraging.” It was a follow up to the book he, Bob Elliot and the team over at Bridgewater put together called Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises. It’s only 480 pages, we’ll wait here while you take a gander. Worth it.

Today we’re going to apply this framework to China to argue that we are entering the Depression phase. The second, slightly more controversial conclusion is that the length and depth of this Depression will be a function of how long policymakers continue to prioritize maintaining appearances (regarding both their quasi-currency peg to the dollar, as well as the ‘extend and pretend’ solution of dealing with failed firms) at the expense of diagnosing the following questions:

How big are the losses?

Who will take them?

How will failed entities be resolved (borrowers and lenders)?

Where will policymakers draw the “bailout line”?

What tools will they use to write down and recap the banks?

How long will they prioritize the quasi-peg at the expense of export led growth?

This last question calling out the inherent tension between prioritizing maintaining appearances and the process of identifying the problems, diagnosing and implementing the solutions. The inevitable solution being to ‘let the currency go.’ Which then puts the surge of investment in gold in China into perspective.

What is a Deleveraging?

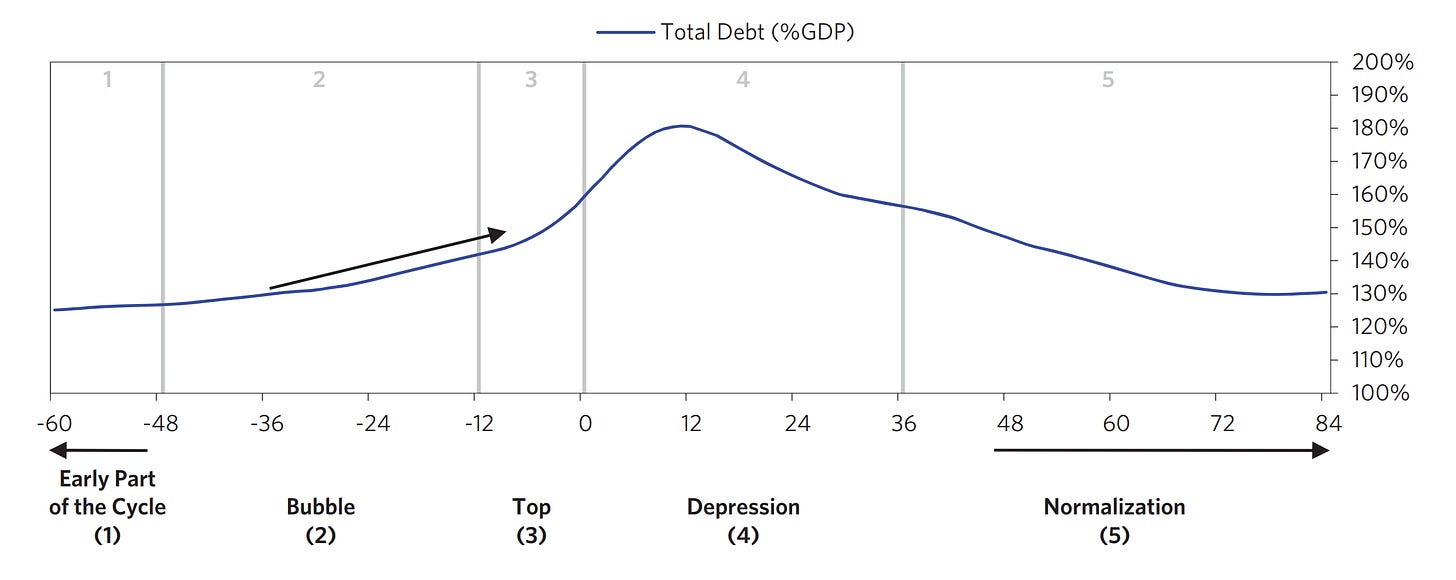

The most important part of the book is the introduction of the concept of a “deleveraging” as a model for how countries navigate big debt crises. The idea that it is the relationship between credit creation to economic activity that drives this process. The pain starts when the ratio between debt and GDP stops growing.

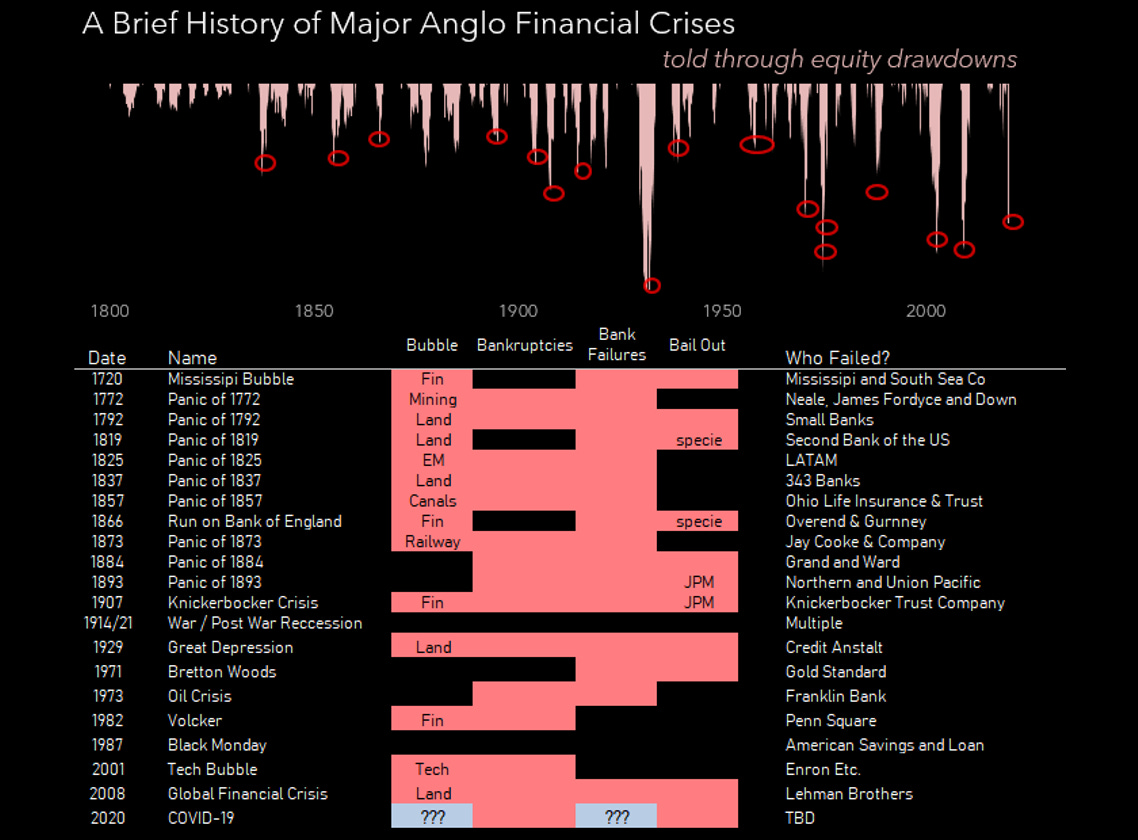

What I find so valuable about this framework is that it not only tells you why financial crises happen, but when. As a Lehman orphan, I’ve always been fascinated with the notion of financial crises, or what they used to call ‘panics.’ A while back my team and I pulled together a list of all the panics we could find in the Anglo world, going back to 1700.

What we saw was that there were clean patterns across these panics. Most panics tended to follow what we jokingly labeled the “Five B Process”:

Boom ~> Bubble ~> Bankruptcies ~> Bank Failures ~> Bailout

Interestingly, most of the biggest bubbles were around legitimate good ideas. Booms that got out of hand when connected to the credit creation machine (canals, railroads, emerging markets, radio, energy, tech) and turned into bubbles. Tightening - even on the margin - then brings expectations and liquidity down, which pops the debt-fueled bubble. This pop creates negative pressure on related players, asset prices and liquidity. This is where you start seeing bankruptcies, which in turn put stress on the credit pipes and balance sheets that financed them. Leading to bank failures (and failures of other levered financial intermediaries). These failures start at the periphery but expand rapidly and in a self-reinforcing way such that it soon threatens the ‘core’ financial system. Forcing policymakers to make a call on what parts of the system get a bailout and what parts are allowed to fail.

We then record these events in collective memory by the biggest name that went bust:

South Sea Company (1720), Ohio Life Insurance & Trust (1857), Overend Gurney (1866), Jay Cooke & Co (1873), Northern and Union Pacific (1893), Knickerbocker Trust (1907), Credit Anstalt (1929), Franklin Bank (1974), Penn Square (1982), Enron (2001), Lehman (2008).

Anyway, my five B framework may tell you the steps in the machine, but doesn’t tell you why it works that way or when it will happen. This is where the ‘deleveraging’ framework comes in.

When the financial system is creating a lot more money and credit than economic growth (“leveraging”) that liquidity goes into two channels: the economy and the financial market.

The economic channel is the spending that the credit creation finances in that period, the support to GDP that comes from a company investing in a new factory or a household buying a new car.

The second channel is the way leverage not only supports this direct economic spending, but it also indirectly supports financial assets as well. So when financial systems create heaps of money and credit, a lot of it leaks back into the equity and debt markets which are financing this borrowing to begin with.

This is the mechanism by which booms become self-reinforcing and turn into bubbles. Given many financial assets are priced on expectations of future cash flows, you can get bubbles when the either the expectations or the discounting gets out of whack:

Excess credit creation thus inflates assets in two ways: the first by pushing up reported (backward looking) economic activity which then flows through into expectations for forward looking cash flows.

The second is the compression of risk premiums associated with those assets, and assets in general. This is a self-reinforcing process, which is why it’s so easy for credit booms to become unsustainable. It feels so good.

Deleveragings are so painful as a mirror of the way in which leveragings feel good: because the interruption of the credit machine bites both of these two dimensions simultaneously. Risk premiums explode as levered players start blowing up, pulling liquidity out of the system and forcing asset sales.

This gets compounded as all of the economic activity financed by borrowing comes to a screeching halt, collapsing current spending and with it expectations of future spending.

This downward cycle is then self-reinforcing, as the collapse in spending makes nominal incomes (and GDP) decline, at the very moment where uneconomic borrowers can least afford an increase in the cost of borrowing!

Worst part of this stage, the notional debt burden (Debt/GDP) continues to rise.

This is Ray calls the “Ugly Deleveraging” (or “Depression”) part of the cycle. The initial period when credit creation has peaked, and contractionary forces start biting nominal incomes but before any of the inevitable restructuring or stimulation has hit the market. Usually kicked off by a huge drawdown in stocks or bubble-related assets.

Most depressions kick off in earnest when this process becomes deflationary. When the collapse in demand just from the slowdown in credit creation is sufficient to put downward pressure on prices.

This last step is particularly difficult insofar as deflation leads to further contraction of nominal incomes just via prices, while the vast majority of debts are held constant in nominal terms. Further increasing the real debt burden (!) while decreasing in debt affordability. All in the midst of a contraction in economic activity. Ouch.

This process becomes outright deadly when the contraction in prices and asset prices is sufficient to push the private sector out of risk investments that fuel economic activity like stocks and bonds, and back into ‘safe’ investments like bank deposits and gold. Which begin to yield positive real returns as interest rates hit 0 amidst falling prices. Typically the depression ends when policymakers…

Watch out for inflationary deleveragings

On the contrary, for economies dependent on foreign capital, this last step occasionally kicks off a ‘inflationary ugly deleveraging’ where the capital flight out of the economy is so devastating that the currency is trashed and this process turns inflationary.

The classic examples here being the Latin American and Asian financial crises towards the end of the 20th century (and to some extent Weimar Germany). In these examples the foreign debt dynamics lead to much more dramatic increases in the indebtedness during the Depression stage.

Note for later that this doesn’t sound very much like China, with it’s domestically financed debt and current account surpluses. To some extent China doesn’t look like a country vulnerable to an inflationary deleveraging, but policymakers continue to operate as if this was their primary concern. We’ll come back to this later.

The Beautiful Deleveraging Requires Tough Choices

Eventually we hit the beautiful deleveraging part of this cycle. This occurs when policymakers have navigated the right balance of a) writing down the debt, b) bailing out the borrowers, and c) stimulating via fiscal and monetary policy sufficient to get nominal incomes growing faster than nominal debts.

Usually accompanied by some form of currency depreciation (vs gold or other major currencies).

Leading to positive growth, positive inflation, and declining debt burdens. Beautiful.

China’s Ugly Deleveraging

In the rest of this piece, we’ll apply this framework of a beautiful vs ugly deleveraging to the current situation in China. With that throat clearing out of the way, the implications are clear:

China’s debt bubble has popped, and they appear headed straight into what we might call a balance sheet or real estate Depression, with no clear path out.

Households and Corporations are already over-indebted, leaving the central government as the only possible remaining sector capable of levering up. Local governments are likely to be a source of liquidity tightness going forward, as much of their revenue derived from land sales, and many failed local real estate projects financed in “LGFVs” will need to be brought on balance sheet as implicit guarantees get tested. Meaning more pain ahead.

The current mix of ‘support the peg’ and ‘extend and pretend’ is primarily responsible for this deflationary outcome.

We are rapidly approaching the point where policymakers will have to make the Sophie’s choice: Maintain appearances, or take the pain, write down the assets, recap the banks, and then try to grow your way out of the depreciation with cheap exports and the worst behind you. Otherwise risk a ‘poorly managed’ deleveraging, where Depressionary period drags on forever due to unresolved bad debts, general apprehension, and a self-reinforcing downward spiral of expectations and liquidity.

Where in the D-process is China?

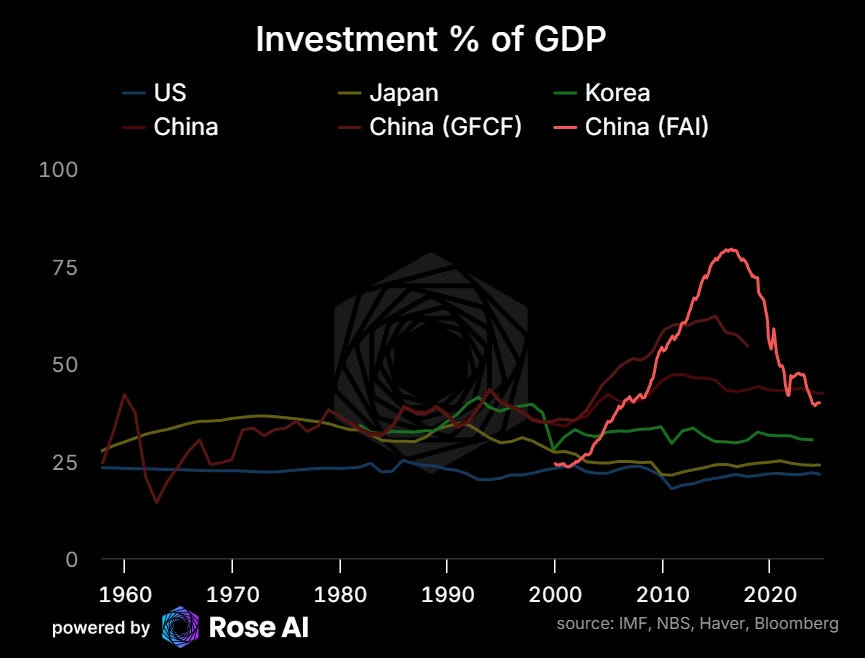

Let’s review. There was a credit-fueled investment bubble in China.

Hard to believe the numbers, but it’s clearly post-peak.

Real estate was at the heart of that bubble. Real estate in China remains the least affordable in the world, even after a couple of years of ~flat prices.

This bubble has now popped. Under the strain from regulatory tightening (“three red lines”), shadow bank tightening (trust products, WMPs, etc), and the impact from Fed tightening on global liquidity.

IEvergrande, Fantasia, Sinic, Modern Land, Kaisa, Shimao, Sunac, Logan, Country Garden. Roughly a trillion of assets sitting in firms trading dead in the water. Not surprisingly the developers with the most foreign debt were the first to go.

Real estate is now a significant drag on growth.

Home prices are now in decline.

Evergrande and co went under with around 100bn of sector wide floor space still under construction. By way of context, all of US residential floor space is around 300bn square feet. Meaning there is somewhere between $5 and $20tr of real estate currently under construction, depending on how you want to value those 100bn sqft! Keep in prices in tier 1 cities are around $750 a square foot, a bit more than 3x the US average.

Meanwhile money creation has collapsed.

Broader prices are as weak as any time since 2008 and falling.

And real time reads of the economy continue to deteriorate.

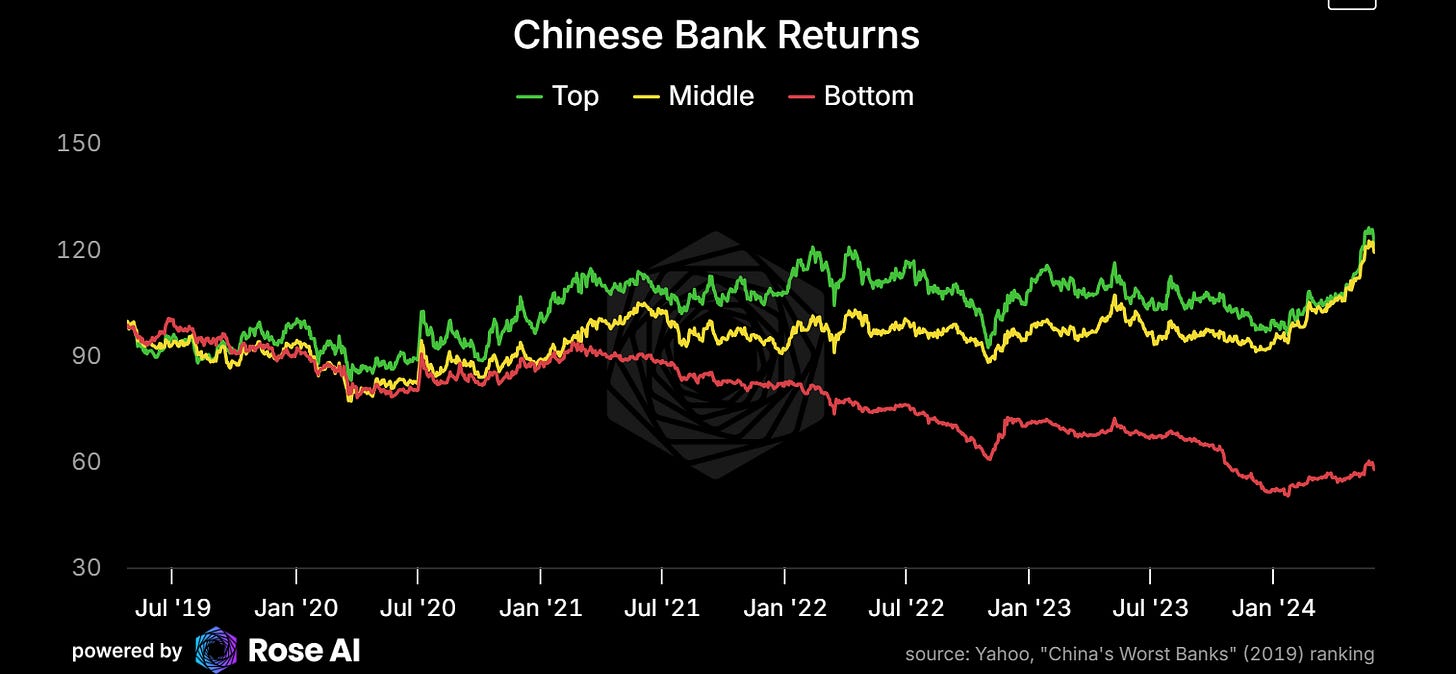

Thus far, the government has pretty successfully built a firewall between the problems in the real estate sector and the broader financial system. Outside of some small failures, and a general appreciation that many of the small rural banks need to be ‘rolled up’ (aka resolved and brought on balance sheet by a larger firm, likely one of the big five).

This policy of ‘extend and pretend’ has thus far been successful, owing to the fact that most of the debt is domestic. While the most vulnerable and risky banks have indeed suffered, the broader banking system has performed reasonably well. Though it’s hard to tell how much of the recent strength in these stocks is as a result of buying by the ‘national team’ in response to the weakness in the A share market a couple of months ago.

The usual argument is that China can just follow Japan and Korea down the east asian deleveraging model. Levering up the government and suffering through extended deflation. What’s interest to us is the way this narrative relies on assuming that China will fall into this pattern when it’s so clear that Chinese policymakers continue to demonstrate real fear of an unmanaged deleveraging leading to capital flight and a return to the inflationary deleveragings of generations ago. China’s commitment to maintaining the stability and strength of the currency has come at the expense of dealing with the debt issue. Directly by consuming some of the literal reserves they have on hand to deal with the problem (which are looking less and less robust everyday), and indirectly insofar as it takes valuable state capacity to deal with what is going to be the mother of all local bank roll ups.

Meanwhile domestic capital continues to flee risky assets like stocks and bonds for the safety of government bonds to such a degree that last month the government had to name and shame the local bank buyers.

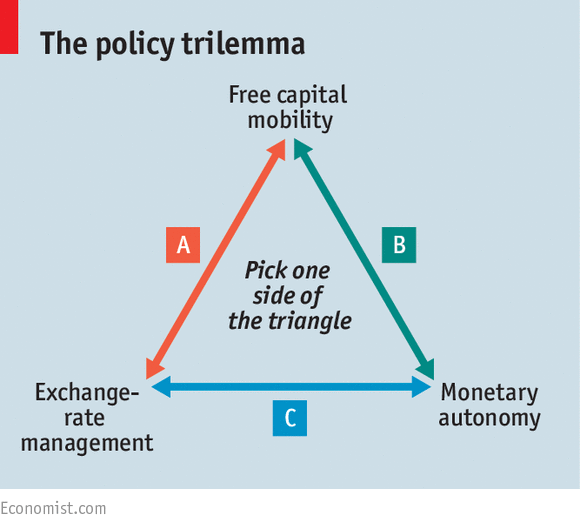

Finally, as policymakers turn back to the pre-real estate bubble model of a closed capital account and an export led economy, the commitment to a strong yuan works directly against the objective to stimulate. The desire to have a steady, strong and controlled CNY come directly in conflict with the idea of growing your way out via exports. Particularly in periods of Fed tightening. Yes, China is the world’s leading manufacturing power, but they are losing valuable time.

Time wasted while the losses accrue and the uneconomic behavior continues. Meanwhile western powers threaten higher tariffs, threatened by the rise of a more belligerent China. Implicitly turning their back on the liberal, post-war WTO-era, “Washington Consensus” in the process.

China’s pivot then to the global south as a source of demand for exports is not only wise but timely.

However, the question remains whether those countries can grow domestic demand fast enough to continue to soak up Chinese’ exports, without seeing commensurate demand growth from China for imports of their own products..

Particularly in an a world where China’s depression means less investment abroad.

At this point, China has had almost 10 years to think through how they want this process to go, yet seems paralyzed between two goals previously out of conflict: protecting domestic asset prices and protecting the value of the currency.

These delays causing further losses and entrenching deflationary expectations. Which in turn lower asset prices, which in turn add deflationary pressure to the depression pressure. Giving us a classic case of bringing about the very fragility you hope to prevent with efforts to control an inherently chaotic system.

The fact that China faces any tradeoff at this point somewhat surprising, given they have openly flouted the holy “policy trilemma” for going on twenty years. Somehow managing monetary autonomy, a closed capital account and the ability to manage their exchange rate. At least on paper.

This system is now an albatross around policymakers’ neck, as they spend more and more energy keeping up appearances, and less and less energy fixing the underlying problems. Every $10bn of bonds spent defending the peg and the appearance of normalcy is another $10bn of USD liquidity they don’t have to act as collateral to recap their failing banks, property developers, and provinces. The more you deny the emperor has no clothes, the less clothes he has on. Or something.

While many claim that the adjustment in the Chinese economy has already occurred, and that the evidence is in the form of the massive investment in green energy and high tech manufacturing, a closer look at the underlying system reveals pretty much nothing has changed. Chinese policymakers, unable to wrangle the internal interest groups, have basically abandoned the possibility of working through the debt problem in a transparent, accountable, and effective way. Preferring to double down on not only old economic principles, but old economic narratives. The idea that they can simply grow their way out by getting really good at the next big thing is naive, given the scope of the bubble.

Were the problem localized to a particular industry or region it might be possible to get away with it, but the debt problems in China are pervasive across balance sheets and regions, and centered in real estate. The single biggest and most important asset class not only in China, but for historical credit bubbles. $10tr is a LOT of unfinished real estate, even if you do happen to have $3tr lying around.

Were it possible to extract enough demand from the rest of the world it might be possible to fill in the balance sheet hole in the Chinese banking system with legitimate growth and earnings. However, there does not appear to be enough demand for Chinese exports to grow at such a pace, and so what we see is the opposite. Not only slowing credit creation (from financial institutions furiously trying to avoid realizing/crystallizing losses), but low and falling prices. A deflationary deleveraging. A depression.

Meaning in their pursuit of extend and pretend, Chinese policymakers have locked in the very set of deflationary expectations that ensure a depression. Putting further pressure on debt affordability, as nominal debts continue to escalate relative to nominal incomes

In the meantime, we’ve seen a significant effort by policymakers not only to support their existing narrative, but to obscure and hide not only the magnitude of the losses, but the magnitude of the capital flight emanating from China. Adding up just the Errors and Omissions from the balance of payments implies more than a trillion of previously under-reported capital flight.

Leading us to believe that the capital flight problem is worse than reported, meaning that when they inevitably do let the currency go in response to intolerable domestic credit pain, the move likely be faster and more dramatic than many appreciate. Bringing us back to our original framework for how this all plays out:

If they protect domestic asset prices, they have to let the currency go, and the CNY will depreciate.

If they keep policy tight in order to protect the currency, the banks end up going, pushing households (and officials) to shift their marginal savings into gold (and silver).

Putting those two legs together gets you our preferred way for hedging the different ways the depression in China can play out. Long Gold in China (aka selling CNY to buy gold). Where you make money on the currency leg if and when they eventually stimulate, and make money on the gold leg in the duration as the credit pain spreads to the banks.

Until next time.

Disclaimers

Charts and graphs included in these materials are intended for educational purposes only and should not function as the sole basis for any investment decision.

This is not my full time job and I do not promise the data included is accurate or up to date. There are innumerable small logical and mathematical decision inherent in making these charts, and mistakes do happen. Please consult me on anything contained herein before making an investment decision on the basis of this work. We are happy to provide the source and business/transformation logic where appropriate.

THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT ROSE TECHNOLOGY INVESTMENT OBJECTIVES WILL BE ACHIEVED OR THE INVESTMENT STRATEGIES WILL BE SUCCESSFUL. PAST RESULTS ARE NOT NECESSARILY INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. AN INVESTMENT IN A FUND MANAGED BY ROSE INVOLVES A HIGH DEGREE OF RISK, INCLUDING THE RISK THAT THE ENTIRE AMOUNT INVESTED IS LOST. INTERESTED PROSPECTS MUST REFER TO A FUND’S CONFIDENTIAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM FOR A DISCUSSION OF ‘CERTAIN RISK FACTORS’ AND OTHER IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Appendix: Prior Work in Chronological Order (2018-2024)

LINKS

Economist - Miraculous Conversion, Day of Reckoning for China Trusts, NBER Working Paper, Ugly Deleveraging Notebook, Credit Update Notebook, China Credit Dashboard, Land Sales Tracker Notebook, China Bank Balance Sheet Notebook, Good vs Bad Banks Notebook

Great piece

Very interesting, great analysis.