Evergrande: End Game

December 7th, 2021

End Game

Evergrande finally died last night, though you would be hard pressed to find a media report on the topic willing to use the word bankruptcy.

For review, the largest property company in the world failed to pay an interest payment on one subsidiary bond (Scenery Journey), blew through the 30 days grace period which expired midnight on the 6th of December, refused to make good on a guarantee of another ‘sub’ (Jumbo Fortune), published a statement warning holders of their financial securities to expect loss, and announced they are in the process of forming a creditor committee.

S&P said a default is ‘inevitable’ and yet no one will come out and say it’s already happened.

For the first time we have an answer, there is no private company in China that is too-big-to-fail. The narrative is the failure will be managed. Bankruptcy with Chinese characteristics. US stocks are up 2% since midnight.

At Oxford, we talked a lot about ‘backward induction’.

The idea that if you know how the game ends, you know the middle.

If you know the middle, you know the opening.

And if everyone knows all the optimal openings, and this is common information then:

Game Over.

With certain games, once you know the end state, it’s not even worth playing.

The 100-year success of the “Mutually Assured Destruction” policy between the Soviets and the West provides good example here.

Another example is tic-tac-toe; once you know the basics, it’s either entirely solved or entirely up to chance.

With the great game that is investing in the Chinese financial bubble, we don’t yet know how it ends, but this week, we may have gotten to the end of at least one of the chapters:

End game for Evergrande.

Their bonds are trading at ~$20, the Hopson bailout failed (because Hopson could not secure financing from quasi-state lenders); they liquidated what assets they could, and the CEO has been asked to prop up the company’s liquidity position, and in doing so, take some exposure to the liability side of the balance sheet.

Yesterday, the grace period expired on a sub-debt they have guaranteed. They did not pay.

We have a word for this in finance:

Bankruptcy. Game over. Do not pass go, do not collect $200.

So, what happens now and how much does contagion demand further stimulus?

The Next Chapter

In the west at least, we have a playbook for the next step. Resolution, restructuring, bankruptcy. All velvet words for the process by which those that lent the company money in the form of debt, take assets and control away from those that ‘own’ the equity in the company (usually some assortment of management and strategic & public investors).

Thinking back to the classic lemonade stand business model, if the lemonade stand goes under, it’s usually easy to work out what the bank gets. The reality of most corporate bankruptcies, in spite of decades of well-fed lawyers, is that it’s usually not clear from the balance sheet who gets what, when. This is doubly true for large, international conglomerates with highly levered and financialized balance sheets.

As opposed to the lemonade stand and the local bank that lent money for lemons, Evergrande has thousands of different creditors, spanning tens of countries, across various regulatory environments. Investors range from professionals to individuals, spanning local suppliers, workers, pension funds, households, and other property companies. In some cases, Evergrande had recognized pre-payments for yet to be delivered real estate or worse, wealth management products (WMPs). They look like deposits for the lender but act like equity.

When I first heard about WMPs, I thought a Rubicon had been crossed: allowing lower-tier banks to package the worst debt in the system and sell it to mom-and-pop investors (in the form of quasi-guaranteed financial products 1 ) went above and beyond anything that Lehman and Wachovia were allowed to do in the runup to 2008.

It turns out I had underestimated the extent of the innovation at play in these opaque products: not only did banks issue trillions of RMB of them, but so too did over-levered corporations (like Evergrande). We are now left with households who expect Evergrande to deliver a dream home in the future, along with an 8% return on a side investment product; with those claims now trapped in a restructuring process that has never really been tested.

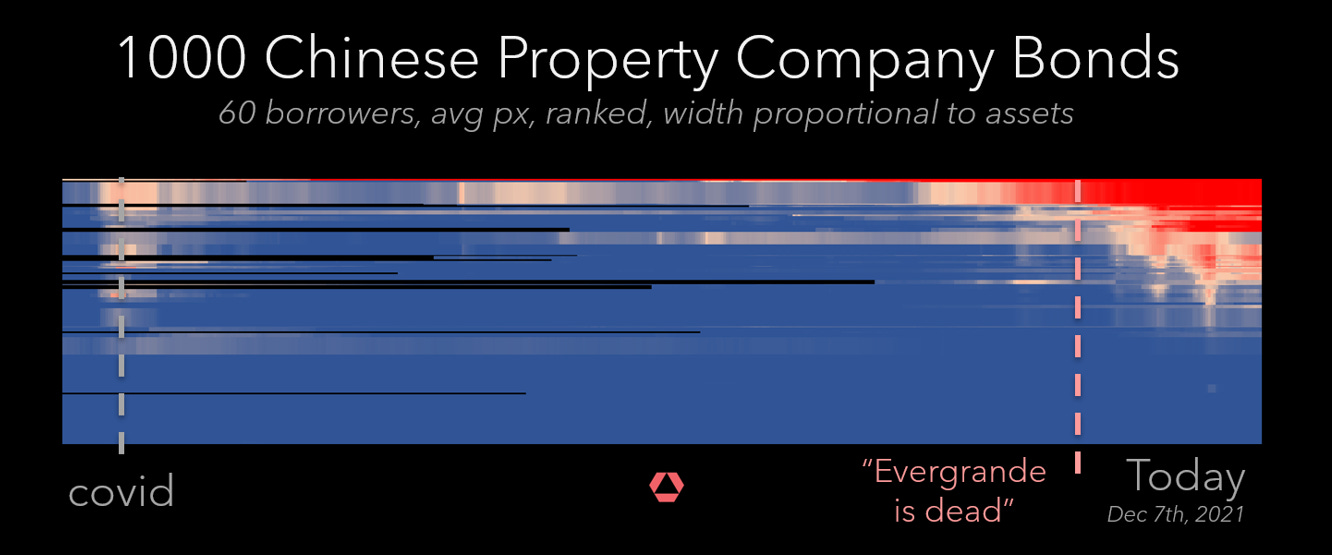

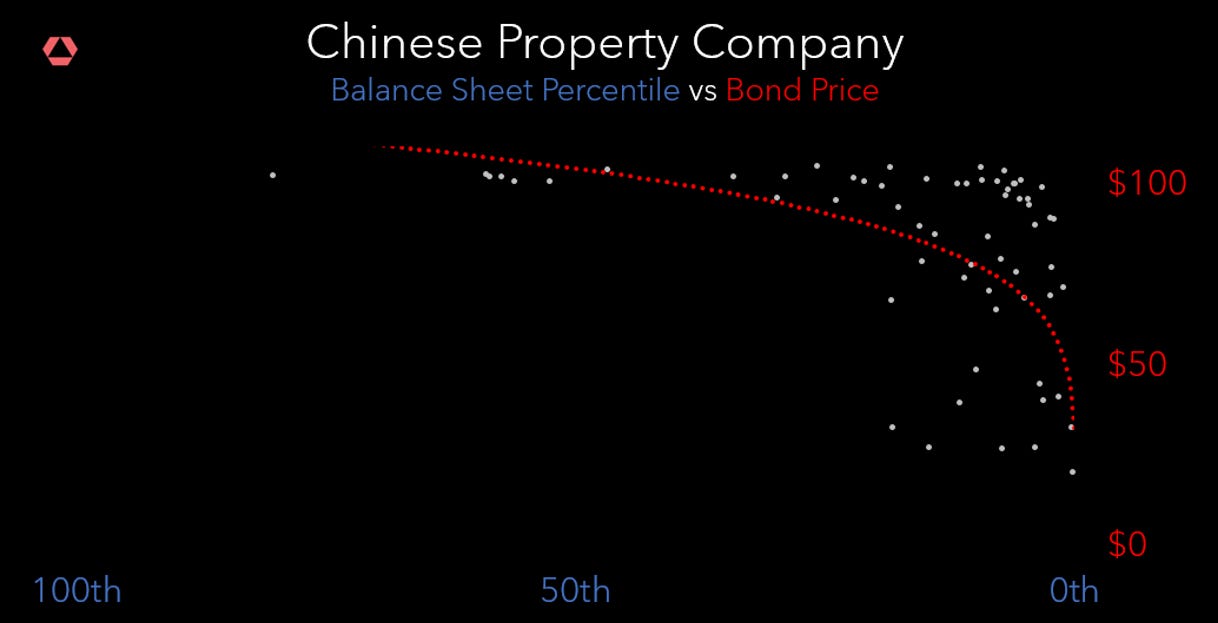

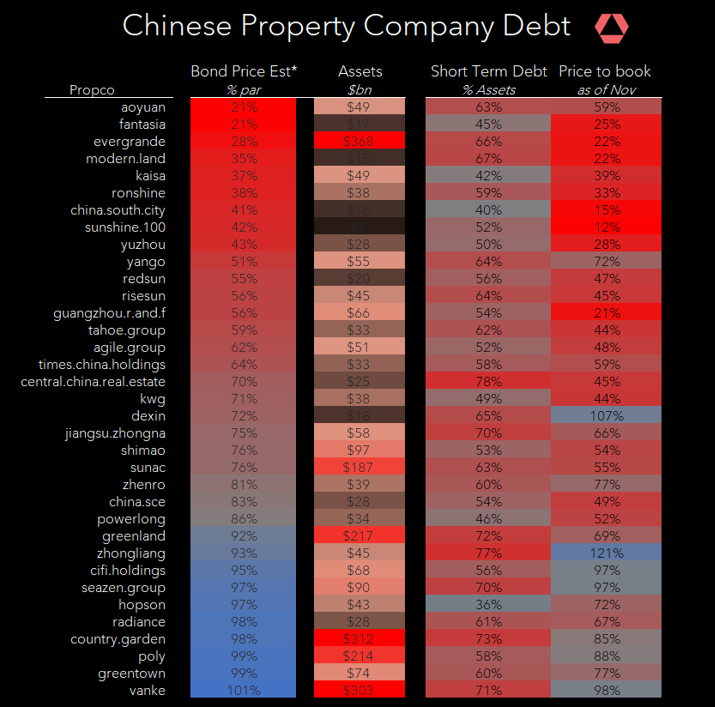

Below we show recent bond prices for the sector against our rankings of their balance sheet health2. Not only do we know there will be actual losses here, but it looks like the credit markets are beginning to be able to differentiate quality. Aka, in a land where no one is too-big-to-fail, it pays to start to be stingy with lending to the riskiest developers!

Chaos to Come or Business as Usual?

Why this all matters: we have never seen a public bankruptcy of this size in China. Nor a payment failure with the current dynamics of global institutional lending, and international investors and local households competing for shares of a fixed pie (i.e. whatever value is remaining).

This is where things get interesting: now, more or less for the first time, we get to see the process in action. Who wins, who loses, and who ponies up to smooth things out?

Remember this is just one gigantic company, but there are 20 more just like it, with worse smaller balance sheets and political connections, but debt trading in the 20s-40s. Now that we know the end game for Evergrande (no bailout), investors can start to do similar math on Kaisa, or Sunac, or even Country Garden - developers with $50-200bn of assets which have looked vulnerable just in the past month. So while this sorting process gets underway, the market is conducting its own stress test. As liquidity and credit slowly leave the space, the most aggressive, uncreditworthy borrowers are now clearly identified - we know who’s next.

The next step now must mean policy easing: easing on rates, easing on bank reserve ratios, and an attempt to direct some of the money flow from the bad companies to the good. The problem though is that the good companies will now face systemic pressure resulting from the clear failure of Evergrande. Foreign investors and local banks alike will have to crystalize their losses, likely forcing tighter risk and liquidity conditions on the rest of the names in their portfolios.

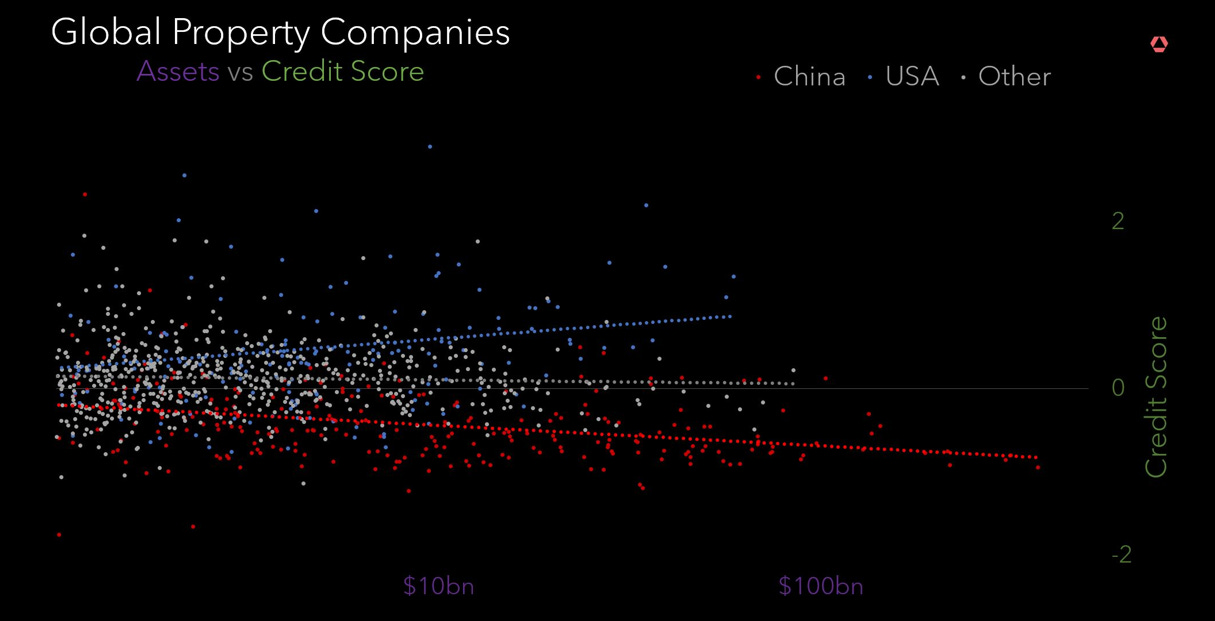

In the rest of the world, developers with the best underlying economic models have tended to scale fastest. In China, due to the inherent nature of the ‘too big to fail logic’ there has been no real constraint on the pace and magnitude of leverage in the sector. The chart below shows this by plotting the size of the developer against our scoring of their balance sheet health.3 As you can see, in the US bigger is usually better. In the rest of the world this relationship is relatively flat, and in China, bigger is usually worse. Which makes sense in the old world, where big could never fail. This is no longer true.

Suppliers of everything from workers to concrete, to copper wire will now have to write down their exposure to Evergrande, and in the process, re-apprise their appetite for lending money to customers.

Meaning they can’t grow their business by lending to their customers anymore, implicitly creating credit as trade payables balloon to hundreds of billions 4.

That financing flow from the private sector suppliers will now stop, and more purchases will be paid in cash and not credit.

Meanwhile, we are likely to witness a relative wave of real estate supply, as properties good and bad flood the market, seeking a bid to make creditors happy; in turn imposing downward pressure on real estate values, the very collateral backing the entire chain of leverage.

Were this to turn systemic, we would expect the weakest banks in China[5] to materially underperform the rest of the sector, as losses in property begin to put pressure on their business model and funding structure.

Against this, the PBoC is easing.

Amidst this, the Fed is tightening.

This could get bumpy.

Disclaimers

This presentation is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy securities in any fund Rose Technology manages. An offering will be made only by the confidential offering memorandum, subscription agreement and other relevant documentation of any such fund (the “Fund Documents”), which should be read in their entirety. No offer to purchase securities in a Rose fund will be accepted prior to receipt by the offeree of the Fund Documents and the completion of all appropriate documentation. None of the interests or shares will be registered under the United States Securities Act of 1933, as amended. Funds managed by Rose will not be registered under the United States Investment Company Act of 1940, as amended. Neither the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission nor any State Securities Administrator has passed on, or endorsed, the merits of any such securities. Registration of an Investment Adviser does not imply any certain level of skill or training. This commentary has been provided to you in a private and confidential manner. It is not an advertisement and is not intended for public use or distribution. It is not to be reproduced or transmitted, in whole or in part, without the prior consent of Rose Technology.

Charts and graphs included in these materials are intended for educational purposes only and should not function as the sole basis for any investment decision.

Rose research is based off information and data from public, private and internal sources. External sources include the Federal Reserve, National Bureau of Economic Research, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Monetary Fund, International Energy Agency, US Department of Commerce, US Department of Agriculture, US Geological Survey, FDIC, Bank of International Settlements, United Nations, Bank of England, PBoC, as well as information companies such as Bloomberg Finance L.P., Global Financial Data, Macrobond, Haver Analytics, Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, Thomson Reuters / Refinitiv, Preqin Analytics, Crunchbase, MStack, Yahoo Finance and Rose Technology. We do not assume responsibility for the quality of this information.

THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT ROSE TECHNOLOGY INVESTMENT OBJECTIVES WILL BE ACHIEVED OR THE INVESTMENT STRATEGIES WILL BE SUCCESSFUL. PAST RESULTS ARE NOT NECESSARILY INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. AN INVESTMENT IN A FUND MANAGED BY ROSE INVOLVES A HIGH DEGREE OF RISK, INCLUDING THE RISK THAT THE ENTIRE AMOUNT INVESTED IS LOST. INTERESTED PROSPECTS MUST REFER TO A FUND’S CONFIDENTIAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM FOR A DISCUSSION OF ‘CERTAIN RISK FACTORS’ AND OTHER IMPORTANT INFORMATION.

In the form of quasi-guaranteed financial products with an alphabet soup of acronyms (WMPs, DAMPs, Structured Deposits, Trust Products, Entrusted Loans etc. etc.)

As always, details available upon request to those interested in methodology.

Again, methods and data available upon request.

Which then find their way via aforementioned ‘channeling’ pipes into financial products sold to corporates and households as wealth management products (WMPs)Again, methods and data available upon request.

As defined by our earlier work “The Worst Banks in China” (2018)