What Evergrande Means to an Old China Bear

September 17th, 2021

Six years ago, I left the world’s biggest hedge fund to short China.

A couple years later, I was out of my non-compete and open for business.

In 2018 we started shorting the worst banks we could find.

We also shorted Evergrande.

The biggest debtor, in the most heavily leveraged sector, in the biggest ponzi scheme in the world.

What if you built a hedge fund to short China, and nobody cared?

A year later the worst bank in our short book died, and got bailed out by Evergrande herself.

The worst bank from our work, getting bailed out by the bad property company.

You couldn’t make it up.

We went on TV, tried to explain the complex shadow banking system underpinning it all.

Why?

At this point, you’d be fair to ask, “Why would you do such a thing, China is the biggest growth engine the world has ever seen?”

Which is what we thought. Before we saw the chart below.

If the Fed money printer goes ‘brrr’ the banks in China go “$Trrrrrrrr.”

Where’s all this money going?

Well first to debt.

Then to investment.

It’s easy to forget but the asset you and I call money is the bank’s liability.

When JP Morgan extends you a mortgage, they don’t give you gold bars. They give you ‘money’, in their bank, in the form of a deposit, to pay for a home.

A liability we call your asset. An asset we call your liability.

In most cases, the expansion of money in the bank is a direct consequence of an extension of credit. Aka more loans, aka more debt.

What are people borrowing for? Well, to invest of course.

You have the privatization and industrialization of the world’s biggest population center as a secular trend. On face, this is a terrific, phenomenal even, place to deploy capital.

And indeed, over the past ten years, China has engaged in an investment boom the likes of which the world has never seen. I will say this again, with emphasis, in the history of recorded economics (100~250 years) no country has ever had an economy so dependent on investment as China.

Keep in mind, finding data in China is always a bit of an art. You may have to deal with Soviet-era year to date accounting that beggar’s belief.

For example, Here’s the official National Bureau of Statistics data on “Fixed Asset Investment” which at its peak in 2017, was reported at more than 70% of GDP!

Ok so the financial system in China has created a lot of debt, to finance a lot of investment in real estate, so what?

Well, investing in real estate itself is not a problem. The problem comes in when all that printed money and credit goes into buying real estate that people either don’t need, can’t afford, or is too expensive. In China, we now have all three.

Real estate in China, in price per square foot terms, is now about as expensive as real estate in America. And the incomes of the borrowers in China are 1/3rd of those in the west, still.

Printed money and credit, going into investment, primarily in real estate, infrastructure, and development, at valuations that nobody really believes.

“Find the Bad Debt. Find the Trade”

But what do you do? Well, we tried what any good macro investor would do. We started digging into data.

“Find the bad debt, find the trade” – mentor at the old shop used to say. Voice ringing in the back.

Well, we did that, starting with the provinces.

Finding a story as old as time. A prosperous, growing and rapidly industrializing coast financing internal infrastructure investments in the hinterlands.

Sounds familiar! The history of US didn’t develop so differently.

So you go and track those down. Try to find how this usually goes.

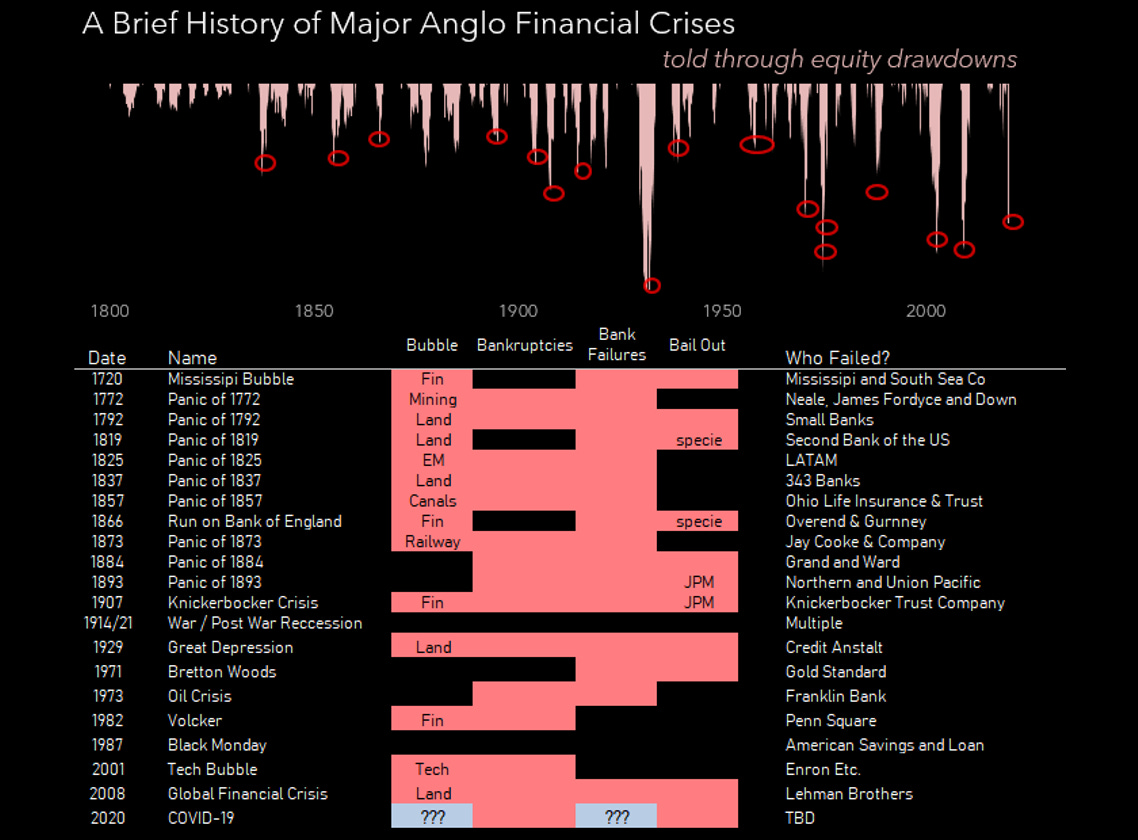

Boom->Bubble –> Bankruptcy –> Bank Failures –> Bailouts

Every time. The same machine in different guises.

The credit problems usually starting with a boom, at the periphery of the old and the new. The value derived creates good collateral for an explosion in money, which is where you get the most intense bubbles. Eventually promises outstrip fundamentals, and people start going bankrupt. If those bankruptcies are big enough, or the banking system was sufficiently exposed in a levered way, it becomes systemic. Bank failures begin, and the self-fulfilling spiral of asset sales forces policymakers to contemplate a bailout.

While today there’s problems in Liaoning, or Gansu or Shenzhen, just a couple generations ago, the Erie canal connected the great lakes to the Hudson, and by association, to the ocean and the world. Setting off a canal boom which would collapse in 1857 amidst bankruptcies and the failure of Ohio Life Insurance and Trust. Years before it was turnpikes. Years later, the radio and the internet has their moment in the sun. Each advancement in infrastructure, bringing the periphery closer into the orbit of the core by reducing barriers in transportation and communication.

This process (usually) completes when policymakers decide who gets bailed out and at what price.

Find the “Bad Banks“

So, you use this knowledge about *where* the problem is to narrow down *who* is likely to need help.

Look for the classic signs. Too much leverage.

Too much risk-fueled greed. Too little liquidity to weather bad times.

Find the bad debt. Find the trade.

Which is a lot of tables of data, like the one below. Combing through financial indicators like leverage, liquidity, and asset quality. Finding esoteric and opaque balance sheet item called an “investment receivables,” where the most profligate banks hide their non-loan assets. Another manufactured term for a financial product which doesn’t fall under the traditional deposits->loans relationship, which regulators use to monitor financial risk.

Pulling that together, you rank the banks, which gives you a set of bellwethers to gauge the conditions facing the most over-levered and under-capitalized.

Applying the classic template of periphery-core contagion, that ranking of financial vulnerability becomes a potential waterfall of pain.

Giving us a signposts to the three ~trillion-dollar banks big enough to represent an existential threat (Industrial, Minsheng, Merchants) , and the five big banks that will be called into “national service” to bail them out in the end (ICBC, Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Ag Bank of China, Bank of Communications).

Weapons of Mass Ponzi

Along the way you learn *how* the wheel turns.

How the Evergrande’s of the Chinese financial system ‘channel’ their short-term liabilities into quasi-deposits called “Wealth Management Products”. Short term debt that in many cases is off-balance sheet for the sponsor banks that package them and sell them to households as quasi-deposits.

Safe as sugar with an 8%+ yield, no FDIC, and daily withdrawals.

What could possibly go wrong?

No surprise, it turns out now that Evergrande was jamming these down employee throats. Making payroll by paying in WMP paper. Paper that they are now trying to swap back into property.

Like the over-levered farmer, paying his mortgage in wheat and pigs.

When paper fails, the return of barter.

As an aside. anyone else think Tether stablecoin holders are going to be excited to accept physical delivery of Chinese property in exchange for all the CP in their ‘USD reserves”?

Which brings us to today, and the slow-motion train wreck that is the Evergrande quasi-default and the questions that it raises.

But how big is the problem?

$5tr of Assets in Plain Sight

You would be forgiven for not knowing that there are $5tr of Chinese property assets in the top 100 global firms, dominating the rankings. Until we made this chart, we had no idea either.

At this point in the story, you’d also be forgiven for not knowing that, over the past decade, these companies have basically quadrupled their leverage.

Levering up their equity to load up on (relatively) illiquid inventories

Financed primarily not with equity or even traditional debt, but a toxic combination of short-term paper, payables, and other current liabilities. Given the size of the sector, these liabilities now approach the magnitude of the PBoC’s reserves.

You might think, this isn’t limited to China, there must be similar companies abroad. But when you compare other countries to China, the system looks more unsustainable in the long run than anywhere else. Because when you have structural incentive for the biggest financial players to also be the most aggressively leveraged and poorly capitalized, it means those incentives don’t just bind at the top, they flow all the way down.

An entire $5tr asset class (and one of many sectors in China with similar leverage models) with everyone all running as fast as they can to grow grow grow, borrow borrow borrow, sell sell sell. And what happens when the music stops, and we need to start paying back investors with 50% discounted parking lots and half-finished apartments?

But how to size the loss or gauge the problem? Well, try repeating the ranking process, this time for the biggest property debtors. Ranking them by liquidity, leverage, and the volatility of their equity and debt. Giving you another ranking, by which to order an investigation into the age-old questions: Who will take the loss, how big will the losses be, and what’s the process by which this all goes down?

Looking at this list, it’s clear that while liquidity is absolutely tightening, and the worst of the worst look almost mortally broken (R&F, Fortune, Greenland, Sunac, Aoyuan, Kaisa, Central China will need intervention soon), the pain has yet to really kick in in a broad and deep way.

It also doesn’t hurt that Evergrande hasn’t *yet* technically kicked-the-bucket.

Until it does, investors can play the waiting game, moving deck chairs on the Titanic, before the credit event crystalizes the loss. A classic strategy to extend and pretend, let the Twitter mob move onto its next target of vitriol.

But there isn’t infinite time. Markets are re-opening. Interest and principal are coming due. Debt needs to be restructured, and it looks like there will be some court cases down the line. These things take time for one developer, let alone the process, pain and politics that will be required if the entire sector needs a full-scale deleveraging.

Which after all, is what is sounds like Xi wants.

Implications for Markets and Investing

While that restructuring process takes place, no more borrowing.

No more borrowing means no more building, at least for now.

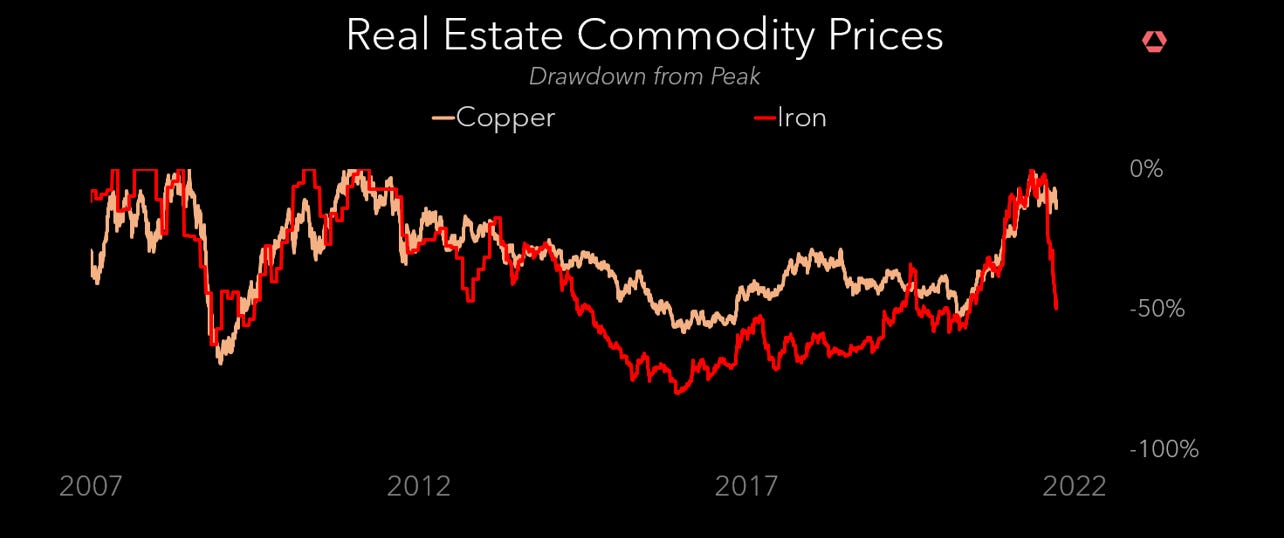

Iron, the homebuilder’s primary food, has promptly taken a dirtnap. Copper a little slower to take note.

Now if we had to guess, based on a combination of history, and reading the Chinese regulatory tea leaves, we think policymakers in China draw the line at the developers outside Beijing’s "three red lines." Letting the worst fail, and then bailing out the debt and (perhaps more important) WMP holders when it starts to look like it might spiral into panic in the banking system.

In a move different than in US and UK historical crises, we think they prioritize domestic (aka RMB-based) creditors at the expense of those that handed over USD to Evergrande for paper.

The foreigners take the loss, etc.

And this probably works! Outside of moves in commodity markets like iron, market conditions appear relatively benign.

Credit spreads in China and the US outside Chinese HY/Prop Cos, have barely moved. Looking at the banks, according to our 2019 ranking, we can see that the ‘bad banks’ in China are indeed underperforming the ‘good banks’ but not in a way out of line with history, or indicative of a real credit crisis. This will be the real tell if things become systemic.

Meaning as of now, the problem appears contained. Whether that continues as debt comes due, management teams get put away for life, and investors and creditors scramble for bailouts, is as of now unknown. Whether this spills over into either an unmanaged deleveraging or an impetus for capital flight, also remains to be seen.

For the time being, and until we get firm resolution on the following questions…

1. Who will take the loss?

2. How big a loss with it be?

3. What’s the process by which all the debt will get restructured?

…the investment implications are relatively straightforward:

1. Near Term: Short Copper (relative to the move in Iron)

2. Medium Term: Short the ‘bad banks’ and (when possible) hedge by going long the ‘good banks’

3. Longer Term: Gold denominated (or funded) in Chinese RMB. To protect against the potential for a broader contagion and a possible devaluation (over time) in response to capital flight

In the coming weeks and months, we will start to get resolution on some of these questions. Policymakers will need to be fast, direct, and clear to the market on how much pain and where it stops. If they give the market a good answer, the pain may stop. If the market weighs that answer and finds it’s wanting, it will move onto the next most vulnerable credit. If the liquidity issues start spreading to other over-levered Chinese sectors (mining, steel smelting, etc.), the WMP issue turns out to transcend Evergrande (of which there is some evidence), or the more levered and exposed banks begin to face pressure, we could still be in the early innings of a time in markets to remember.