Inflation, Deflation, Bubble

October 31st, 2020

I was talking with a friend the other day about the Cold War, in the context of the upcoming election, and he recommend I go re-watch Miracle. The one about the American ice hockey team’s win over the Russians in the 1980 Olympics in Lake Placid, NY. Maybe the last time in 50 years Americans really felt like the underdog.

Here’s a link to the opening credits, we’ll wait here while you check it out.

The opening credits of the movie set the stage in many ways for why the ultimate American victory transcended American culture and was so important, well beyond the incredible accomplishment of that group of college-age kids beating the ‘professional’ Soviet team. We were not in our best place then as a nation and there was pent up demand for a galvanizing event. Worth watching the movie, but here’s a synopsis of the events and issues faced by our nation and the world in the decade leading up to the game:

· 18 year-olds granted universal suffrage via ratification of the 26th Amendment

· The U.S. comes off the Gold Standard in 1971

· Vietnam War eventually ends in 1975, but spill-over wars in Laos and Cambodia humble the nation.

· Nixon goes to China, normalizes relations. Watergate, Resignation.

· Gasoline prices skyrocket as a result of the Arab Oil Embargo

· “It’s Saturday Night Live!”

· The U.S. Bicentennial

· Jimmy Carter elected President

· Elvis dies

· Camp David Accords

· Three Mile Island nuclear accident

· The Iran Hostage Crisis begins; Gasoline price triple to over $1/gallon for the first time

· The U.S. boycotts the Moscow Summer Olympics

· Ronald Reagan elected President

· John Lennon is murdered

· Russia invades Afghanistan and Cold War tensions were at a peak

Personally, I can’t say I remember these events, because I wasn’t alive. I was born in 1982. This was my parent’s experience, cold war, unemployment, social conflict, inflation.

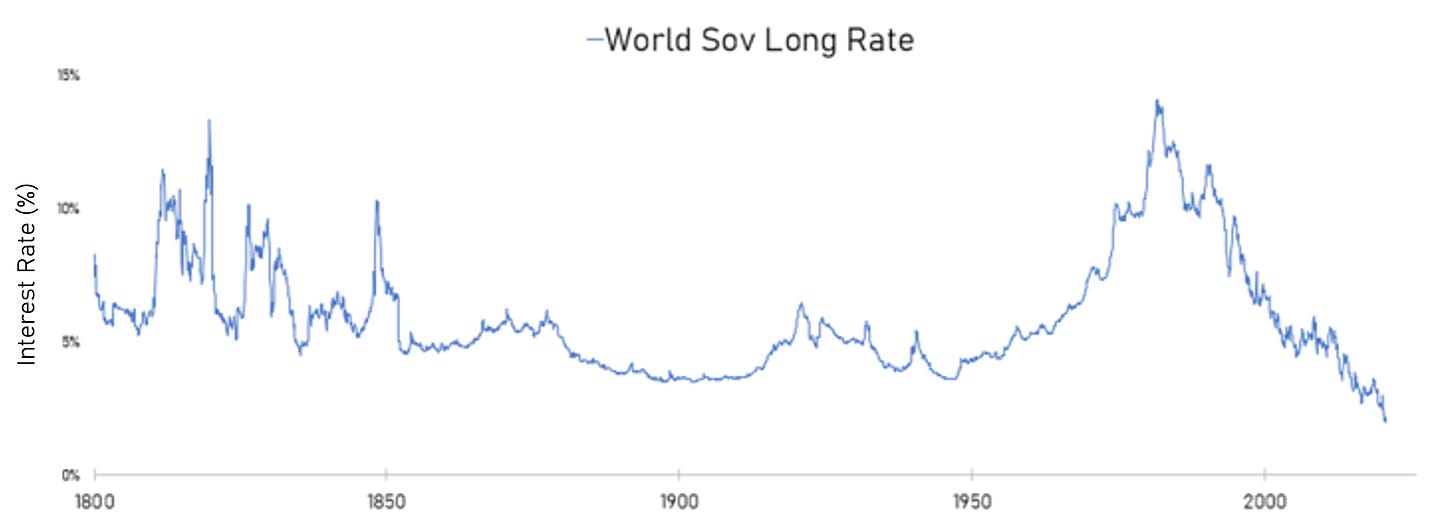

Funny thing, the median American is now 38 as well, meaning, the average American, doesn’t remember the global recession of 1981-1982. They do not remember an unemployment rate above 9%, they do not remember inflation levels reaching 13.5%, and they do not recall the stagflation that followed. And they certainly do not remember mortgage rates ticking up to 18%! That was a different time. The world of Fed Chair Volcker, and the war against money creation. Contrast that with a steady overall decline in the Fed Funds Rate from 1982 to today and 30-year mortgage rates down near 2.5%.

At Black Snow Capital, we have made it a point of studying history to inform our investment perspective. We believe there is alpha in understanding the lessons our generation has forgotten[RS1] .

We started by studying panics and their causes in 2018. We wanted to understand how they worked and what investors could do about them. We laid out the economic machine by which financial panics are seeded (credit), and then unleashed (tightening), and then resolved (the “Four Bs”: Bubble, Bankruptcies, Bank Failures, Bailout) and recommended investors increase their gold allocation, in order to protect themselves from the risk of another financial crisis.

Flash forward two years, and COVID has unleashed the latest example. Though the policy reaction was so fast this time, we kind of skipped to step 4, bail out!

Over the past few months, we’ve undertaken a second leg in that work around panics, this time a study of the long-term drivers of that other destroyer of wealth – inflation.

What follows is a summary of our work, the conclusion of which is that long term inflationary pressures are building, and that whilst absent a global conflict we likely won’t see a massive inflationary shock, we recommend investors consider re-allocating some of their exposure from government bonds, into gold. We may only scratch the surface, but are available to talk through any of the issues presented, and most importantly, assist investors in constructing allocations within their portfolio that can capitalize on the thesis we lay out below.

Inflation, deflation, bubble. Or is it bubble, deflation, inflation?

It’s hard for most people to hold both tails of the distribution in their head at once. Inflation is a tricky concept, in particular, the targeting of ‘not too much.’ The idea that not only is 5%+ inflation possible, but that it might be correlated to (and in some senses caused by) deflation, can be hard to track.

While we see this too, we worry less about the deflationary deleveraging, something modern central banks have proved adept at managing. Of more concern to us is an unwind of the disinflationary economic trends of globalization, peace, and technology which underwrite most, if not all, of the Fed’s disaster recovery playbook.

In short, we don’t worry about policy unleashing the inflationary monster, we worry about conflict unleashing inflation, which in turn forces policymakers to choose between their desire to support asset prices, and their mandate to fight inflation.

The Fed’s Financial Crisis Playbook

Both modern and classical financial systems are prone to panics, as levered players are forced to fire sale assets in order to meet short term liquidity needs. Classical (gold standard) panics are observable as short and volatile boom bust gyrations in short term interest rates. Modern central banks deal with these panics by ‘easing,’ basically providing liquidity to those levered players, in the form of a) lower rates, b) lender of last resort activities, and in some extreme cases c) purchases of public and private financial obligations with printed money.

It may be a little cheeky to call this the Fed’s playbook, since the pattern here goes back to 33AD, when Emperor Tiberius reacted to the popping of a Roman real estate bubble with a 3-year moratorium on interest payments. Nevertheless, at this point the Fed has a 100-year track record of reacting to financial panics in a consistent way. Note, the length and breadth of these cycles tend to be longer and wider in a world off the gold standard, as demonstrated by the 200-year history of British and American short rates above.

The Fed reacted to Covid using the same playbook as 2008 (which was itself similar to the playbook from the late 30s) though with more speed and more coordination with fiscal authorities. That playbook contains the steps below, starting at the top, and working their way down as a given step hits capacity or operational constraints.

The playbook reads as follows:

a. Lower short-term interest rates, to zero, and beyond, if necessary.

b. Buy medium term government bonds, until you run out.

c. Provide liquidity to banks and levered players by lending against “high quality” collateral, until you have to expand your definition of ‘high quality.”

d. Buy long term government and agency securities, until you run out of bonds (and/or until agency spreads are low enough to worry about fueling a housing bubble).

e. After you run out of gov/agencies, turn to corporate credit markets, buying ‘distressed assets, and in doing so, bailing out over-levered corporations that can’t afford to roll their debt at yesterday’s market rate.

f. Direct monetization of government fiscal spending.

g. Finally, buy stocks (either equity stakes in distressed industries like banks in 2008, or the entire stock market if you are the BoJ).

The Construction of a Bubble

So, if the Fed is running a two-thousand-year-old playbook, what’s the problem? Well, here’s where it helps to be a macro guy. Macro guys live at the intersection of markets. Bonds vs stocks, gold vs oil, AUD vs EUR, EM credit or HY in Europe etc. etc. etc.

Being at the intersection of all these markets can be kind of exhausting, especially when you are trying to track every little flow. But it’s also this massive opportunity to see the forest for the trees.

The forest here being that when the FOMC eases by pushing yields to 0, they aren’t just pushing up bond prices, they are pushing up the present value of every discounted cash flow in every asset that directly or indirectly competes for your investment dollar!

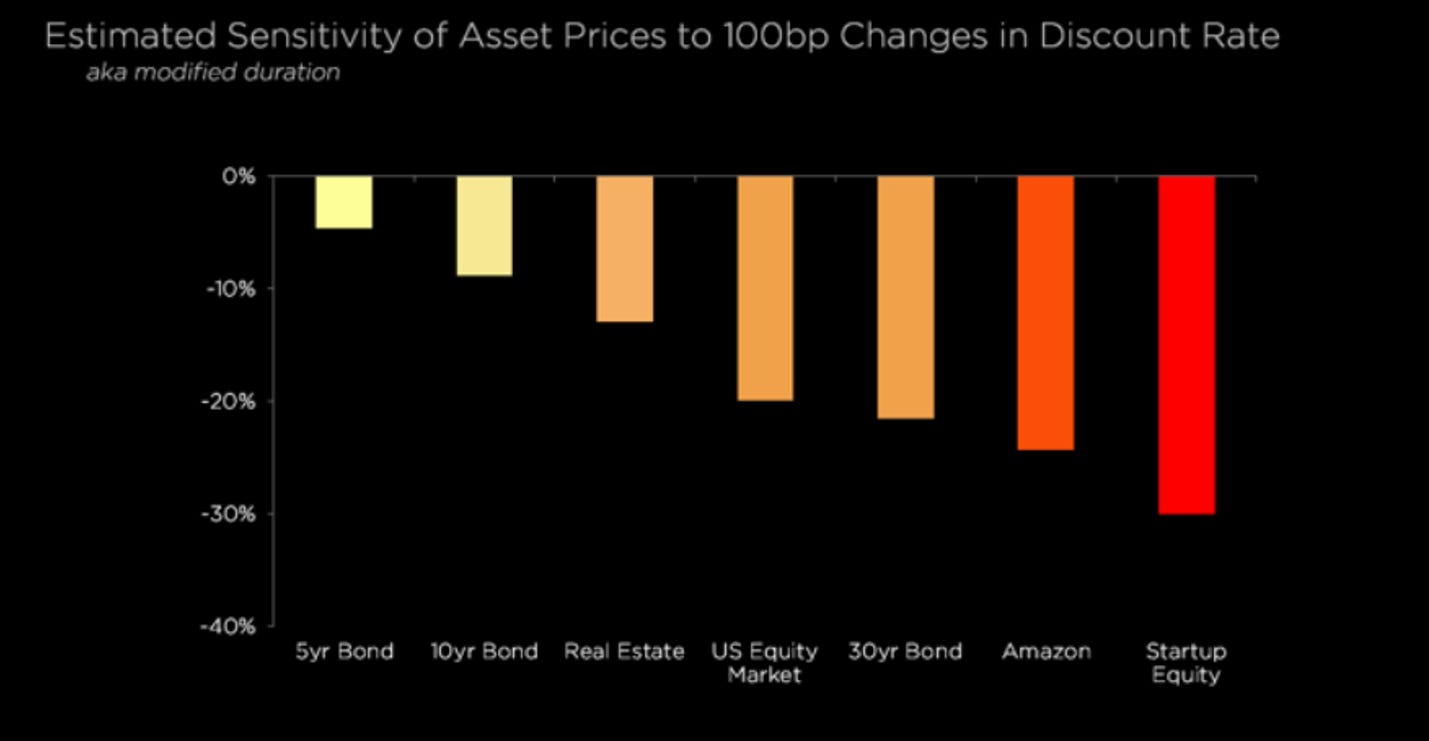

And in fact, it’s the longest duration, riskiest cash flows that benefit the most from this decline in rates.

Not only are there bonds in the stocks, but ironically, it’s the riskiest stocks that have the most bond exposure!

The chart below shows our estimates of the effective duration of many traditional asset classes. No wonder we’ve seen an explosion in PE and VC in the wake of the Lehman crisis – it’s a great way to get exposure to levered duration.

To some extent this makes sense. If interest rates are zero for 20 years, suddenly there’s no opportunity cost for a project which (might) return a boatload of profit in year 21. What do you in a world where your money earns little or negative yield for 20 years? Perhaps give some to Elon to see if he can use it to build cool rockets or replace the internal combustion engine?

Those potential cashflows may be a couple decades out, but when the Fed pushes long term rates down to zero, it’s mechanistically bringing the value of those real (or imagined) future cashflows into the present. Through the magic of present value, what might be worth billions tomorrow is magically converted into billions of value today.

The trap here being you only get to do this once. Today’s pleasure is, necessarily, tomorrow’s pain.

Thus, the seemingly unrelated trends of negative yields, eye watering tech valuations and a 50% gold rally are all representative of the same underlying phenomena, and a direct consequence of Fed policy.

And in fact, in a world where fiscal policy is constrained (because of politics or public opinion), this isn’t a bug, it’s a feature!

If you can’t get money to people directly in a crisis, sometimes the best thing you can do is just fluff everyone’s portfolio.

The Destruction of a Bubble

Many macro folks suggest that by inflating an asset bubble, the Fed runs the risk of manifesting yet another asset bubble collapse. To which we say, yes, but (respectfully) so what?

“To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

– Mark Twain

“To a central banker with a QE playbook, every bankruptcy looks like a reason to print”

-Black Snow Capital

While there are certainly good reasons to be short stocks here (and we are), we believe the biggest risk to the global portfolios is not another short-term liquidity event. One that would inevitably result in more easing and more printing. Rather, we believe the biggest global risk is a shift in the underlying deflationary dynamics upon which all Fed financial crisis policy depends.

Put another way, we’re worried less about the asset bubble, and more about the end of disinflation, which would make the Fed’s promotion of the asset bubble untenable.

This generates a problem with regards to market timing. As PMs, we deal with the problem with an options trader’s mindset. Rather than elaborate on implementation here, we will focus on the fundamental drivers of the cycle.

What will cause the disinflation and what historically has been the primary driver of rising (and volatile) inflation? To answer that, we’ve linked to some of our recent work on the long-term history of inflation. A bit of a chart deck, but worth a scan if you have a minute.

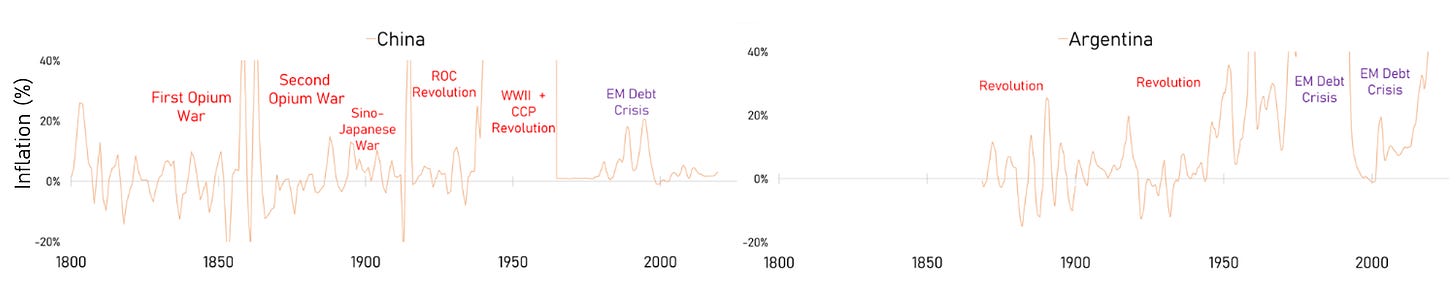

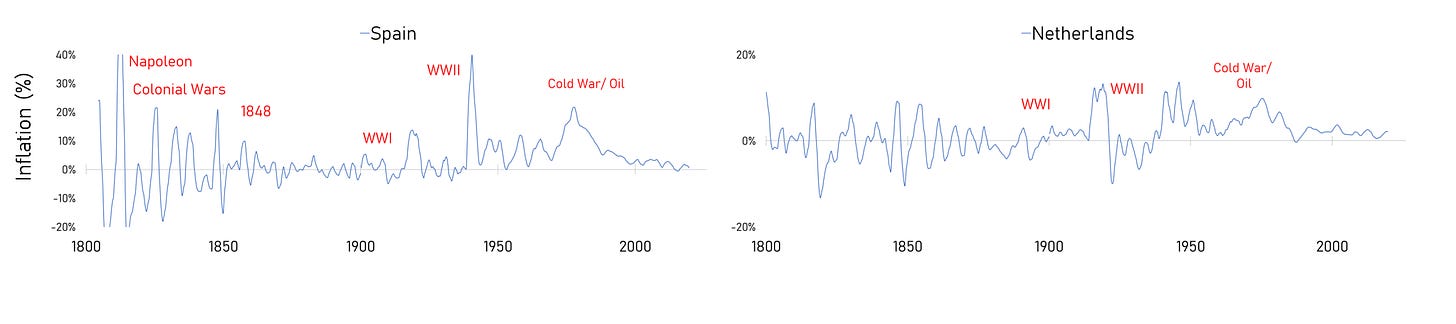

In that deck, we’ve attributed each inflationary event (sustained 10%+ inflation) into one of two categories.: Inflation volatility resulting from financial panics (deleveragings and EM balance of payment crises being the classic example here) vs inflation resulting from internal political conflict or external war..

What you see in the deck, is a lot of charts that look like this:

The pattern here is clear. Financial panics lead to deflation and conflicts lead to inflation.

Occasionally we ease our way out of those panics to get inflation, but generally the largest long-term driver of inflation (especially in the developed world) isn’t policy or bubbles at all, it’s conflict!

Now, one might ask, what type of conflicts matter? Why didn’t wars like Afghanistan or Iraq really register? Looking at history, the type of conflict necessary to register on the scales above usually represents an existential threat to the existing internal or external order.

In this light, the Cold War was a single slow-burn conflict, spread out over 40 years, and constrained in terms of military power by the introduction of the atom bomb. The 50s-80s representing an existential conflict, playing out over a generation through a series of proxy wars and economic tit-for-tat fights.

The first time we saw this was surprising. We spent years learning about traditional business cycle dynamics and never did the role of conflict or war really come up.

The short-term debt cycle and the long-term debt cycle are great frameworks, but if you want to understand inflation in the developed world, it looks like you really, really, need to understand conflict!

This pattern repeats over and over when looking into macro history.

Fight a war, get inflation.

Lose a war…hyperinflation.

Emerging markets have slightly different dynamics. Generally lacking in domestic capital and dependent on the developed world for at least part of their credit system, the role of foreign creditors becomes much more important and determinative. Developed countries, particularly those that issue debt in currencies they can print, seldom go through balance of payments issues of the same nature.

In conclusion, it’s not clear that really anyone is taking this into account, likely due to the brain damage required to clean the data enough to see these patterns. A problem we struggled with so much, we started a data company (Rose Technology) to solve it. So many critical time-series for macroeconomic stats, not just inflation, literally start immediately after the last devastating conflict or hyperinflation.

For example, most Eastern European stats come into being right after the end of the Cold War and the fall of the USSR.

Most modern Western European inflation stats start after WWII, operating from a world of Pax Americana and Bretton–Woods. Go back a little further, and you will find data from the League of Nations stats, immediately after WWI and the end of the gold standard.

Go back further, and you can dig up data on European countries from the Latin Monetary Union, a sort of 19th century test drive for the concept of the Euro.

Go back even further, and you find yourself scraping through French wheat prices from the 1830s or Chinese rice prices from the 1450s, to get a sense of the boom bust cycles of earlier times. Each era, encoding the biases of their time in data, like the way an old tree tracks the weather of its youth in the width of its rings.

Where does that leave us, particularly as investors in the era of low and negative interest rates?

Cautious for one. Not because we think conflict is especially likely (though on the margin the odds feel like they are increasing everyday), but because it’s just so off the map for most investors.

Like, how many folks realize that the single most determinative force in the long term returns of fixed income isn’t the business cycle, but the conflict cycle? How many folks realize that, prior to WWII, the status quo was conflict?

Looking to today, it feels as though we are in the early days of another cold war, this time with China inheriting the role of the USSR.

A newly industrialized Asian land-power, awoken from a century of slumber, stagnation, and civil war, unified by an ideology fusing nationalism with communism and looking to flex its muscles across Taiwan, the South China Sea and the Indo-China border. China has much less history of external war, and more history of internal conflict (see preceding chart), at times when the emperor loses “the mandate of heaven”. With this backdrop of domestic political vulnerability, China’s recent territorial squabbles take on a more deliberate approach. Foreign conflict acts to distract from domestic problems if the credit bubble really does come crashing down.

However, similar to the last cold war, nuclear weapons give both sides a billion reasons not to engage in direct military conflict. What’s more likely than a grand conflagration between the East and the West is a repeat of the Western strategy of fiscal deficits and containment. Recall it took 40 years to shake out the USSR, and the we had to break the dollar’s peg to gold in the process.

Regardless of who wins the big house next week, expect a bumbling path towards a similar cold-war strategy. The US relying on its reserve currency status to engage in competitive deficit financed spending, investing in a combination of bread and circuses at home, the containment of foreign imperialism abroad, and (hopefully productive) competition to develop the new frontiers of civilization.

Given this wider historical context, all the money China is printing (and the credit bubble that money printing supports), starts to make a lot more sense. Maybe it’s us in the West that are wising up to the game of competition through printing and spending. Maybe both sides are just getting started.

Maybe, just maybe, folks have way too many bonds, and not enough gold in their portfolio.