Conflict is Inflationary: Part 2

We remain short bonds, long gold and silver. Though watch the chops.

Back in 2020, when I was still trying to raise money for our “Gold in China” fund, the cap intro guys asked me to do a writeup for Druckenmiller.

Yes, the Druck.

One of the OG macro punters/investors. Part of a pantheon that included Soros, Paul Tudor Jones (PTJ), Kovner, Bacon, Howard, and yes, dear old Ray that defined what it meant to invest in ‘global macro.’

Anyway, so you can imagine my enthusiasm. After three years of pitching, unsuccessfully, the largest capital allocators in the world to sell their fixed income to buy gold, maybe this was “Our Shot.”

We sent the team into a tizzy looking for historical data. Painstakingly finding, cleaning, organizing, and stitching together thousands of timeseries, then spending hours upon hours agonizing over each of the three thousand words. All to justify a very simple conclusion:

Conflict is on the rise.

This will prove inflationary.

Sell bonds and buy gold.

We never got the meeting.

Since then, gold has outperformed bonds by about 70% since our initial writeup, and the macro GOATs are now all over the timeline talking about sell bonds to buy gold.

Life is funny. Sometimes your synthesis can be too simple. So simple they disregard it. Right up until it becomes consensus.

Anyway, the point of today’s post isn’t to crow about our winners (or losers) but to re-examine the case for selling bonds to buy gold in today’s world, after the 70% outperformance and when it may be getting crowded/rich. My view is that, yes, conflict is still on the rise, yes that looks likely to create inflation, which has likely already floored, and yes, the case for selling bonds to buy gold is as strong as ever. Though at some point in this ride, we’re going to take another drawdown, so if this is your first rodeo, try not to go all in on the first hand.

This time we’ll start with an update on the case for conflict. Next time we’ll go through who we think wins and why.

Thucydides and the Case for Conflict

At this point it’s consensus to say that the rise of China will inevitably lead to conflict with the West. This argument usually starts with some reference to Graham Allen’s work on the “Thucydides trap”, referring to the author who first outlined Sparta’s anxieties about the rise of Athens in his History of the Peloponnesian Wars.

Think the first time I heard this idea in the wild was actually also from Ray in his book on the “Changing World Oder”. Worth checking out if you haven’t, even if I could not disagree more with his (implicit) conclusion of China wins, the West loses. Thing is, Ray is wrong. Not wrong on the direction of motion, we’re agreed that you ought to expect more conflict going forward, but rather wrong on the outcome, who wins.

For a start, the problem with the ‘rising power’ theory of conflict is frankly, it’s pretty unscientific and doesn’t even really offer a reason why it’s wrong when it’s wrong. Why does it sometimes resolve in war and sometimes peace? Who can say!

We say unscientific first due to the lack of sample size.

Thucydides had one case study: Athens vs Sparta.

Allen initially published 12 case studies and I think the sample has since been extended to 16.

Basically half of the 30 that the central limit theorem demands!

But even if we did have 30 examples, and we’ll get to that next time when we present our work pulling together 200, there are still big problems.

The second problem with the lack of sample size is it leaves the model ‘underspecified’ and ‘overselected.’

Meaning you have selected such a small sample of the conflicts in your potential set that you know there will be ‘selection bias’ (particularly the ‘representativeness heuristic’ where once you have a hammer of a framework every case study begins to look like a nail.) Anything that doesn’t fit the model, you throw out because it’s too hard to understand. Or #N/A as we call it in the excel file.

I can speak with personal experience on this issue, as after realizing this, we went and did some deep research on conflict, trying to generate that idealized representative sample.

What we learned is that it’s basically impossible when you think about the scope of the problem? Why?

Well, for every rising power that won a battle and displaced the hegemon like England shoving the Netherlands off the world stage (and getting NYC in the bargain), you have a million petty despots that the hegemon left bleeding out by the side of the road/ocean/drab wheat field.

Seriously. We have forgotten more kings knocked off by a single Caesar or Alexander in one good run of the table than exist in Graham Allen’s sample. For every successful Napoleon there’s twenty Vercingetorix and XYZ, and ABC he left out. Where do these go in our sample?

Harder still, how do we determine who is the ‘rising’ power?

Well, historically, with the benefit of hindsight. Of course!

So England becomes rising because of the outcome at Trafalgar and Waterloo, and if the winds went differently, what would our model say? What happens to the R2 of a regression when you flip one binary variable out of 16 from 0 to 1?

This is kind of a pedantic joke, but actually kinda serious, when it’s being used to influence global policy.

We’ll come to this data labeling problem later when we get to adding dimensions to this model, but suffice it to say, it should give you pause, and a desire to go deeper.

The Game Theory of Conflict

Now regular readers will recall that our framework for conflict is so simple it’s almost tautological: actors experience conflict when they perceive their relationship shifting from positive to zero or negative sum games.

When you believe yourself to be in a zero or negative sum game with someone else, the only dominant strategy is to try to win, via any means necessary.

At least that’s what the math says (if you can really boil the world down to one unitary ‘us or them’ dimension, which you can’t, but for the sake of argument).

This model also explains the way that conflict escalates. We go from fixating on winning this tiny part of the zero sum relationship, rather than zooming out to how much positive sum possibilities we are throwing out in that pursuit. Zero sum behavior begets zero sum behavior from the other side, and in the process, we damage the positive sum parts of the relationship. Whether it be bombing an electricity plant or raising tariffs, each action making those positive sum games harder and harder to play.

Seeing this logic play out in real life, via interpersonal interactions, was probably the most rewarding part of going to business school at Stanford. When people say that ‘networking’ was the best part of bschool, I think they are missing the core lesson. It’s not that these people or that connection is valuable, that’s the extractive, zero sum mindset we want to avoid. No, it’s that when we are young, we spend so much time obsessing over this or that zero sum context, making the team, earning the A, getting the romantic interest, we kind of don’t realize that those people we think of as competition, end up becoming our greatest friends and allies later in the life. The guy I competed for literally all of those things in high school ended up as the officiant at my wedding ten years later.

And that logic just keeps growing over time, if you have decent intentions, do good work, and basically hold your word and don’t try to hurt other people, eventually all the good things that happen to your friends also kind of happen to you. Not directly, but in a way where a friends business going IPO, or winning and Oscar, or writing a best seller, these successes actually enrich and open up possibilities in your world. Maybe you wanted to produce a movie when you were old and now they can help make that happen. Maybe you always wanted to see the Grateful Dead and they randomly got an extra ticket to see them at the Sphere. In a very real sense, we are all on the same team.

The thing about the modern west, is that logic goes all the way up to nations. This logic of peace through trade and prosperity has been a bedrock part of western policy pretty much since the disastrous experiment with the opposite in the wake of WWI. Post WWII Europe and Japan are probably our best examples of following through on the positive sum path.

At some point the allies realized that only way to sustainable peace amongst western nations was just to integrate our economies so much that the zero sum stuff just became silly in context. If you want a counter-example here, look at how the territorial dispute between the UK and France over some random island went down in 2021. Stirring up old nationalism that kind of felt ridiculous given the scale of the good vibes in the existing relationship.

Where did we go wrong with Russia and China?

This idea of peace through commerce was the fundamental pillar of both our Russia and Chinese policy. First with Russia’s disastrous shock treatment, which pushed a country prone to despotism into oligarchy, with predictable consequences. Then with China’s accession to the WTO (and along with it stuff like it being cheaper to mail goods from Shenzen to NYC than Missouri), the basic idea was if we help them grow, they won’t grow up so much they decide to come punch us in the nose.

Now that they look like they want to punch us in the face, turns out we don’t want to trade with them anymore.

Meaning the status of the relationship becomes more and more zero sum.

Cut Russia out of the European gas market, they sell more to China.

Prevent them from importing manufactured goods, they start importing dual use products through the stans, chips from China and shells from North Korea!

Cut them out of SWIFT, they start accumulating gold and silver.

Escalate the quality of weapons delivered to Ukraine, they bring in Korean troops!

Each step, a ratchet in both escalation, and the degree to which the relationship has deteriorated. The slow inexorable march to direct conflict. When people ask “how could it be reasonable for Britain to carpet bomb Dresden” or “blockade a million Germans into starvation” you have to consider these things were, at the time, seen as totally reasonable counters to legitimate provocations by the other side.

You know, kind of like trying to assassinate the leader of a democratically elected country in response for assassinating the leader of a quasi-democratic militant group.

That kind of thing.

Before we go there though, it’s important to note that the real starting bell for the big one ultimately rests in the Pacific. As long as the government in Beijing is convinced there are plenty of positive sum games to be played with the west, we can hopefully expect peace. When they become convinced that it really is a zero sum, ‘us vs them’ kind of thing, they will be forced to act, even if they aren’t sure they are going to win.

Which is why the strategic dynamic between the US and China is so interesting, and so potentially chaotic.

Pretty much since the election of Trump, the US has slowly started trimming back on the positive sum games. Playing out a strategy as old as time, one that mirrors how the US instigated Japan in 1941. As that net slowly tightens from the outside, China grips harder on Taiwan, the South China Sea and the other disputed regions. The external encirclement tightening in turn on the inner circle.

Meanwhile China is preparing to defend its critical import channels for food and energy, along with the export channels by which any and all growth is being sourced.

Amidst all of this, why would Russia or China (or really any non-western aligned state) ever buy another US Treasury? We’ve already shown what happens to the coupons when you cross the line?

It’s a miracle folks use them at all! Which makes it no surprise that they are hard at work on a replacement.

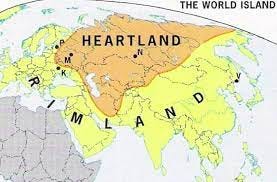

Heartland vs Rimland

The irony of Thucydides being boiled down to ‘rising vs falling power’ is that the Athens vs Sparta conflict is also probably one of the best historical examples of another phenomena, the inherent conflict between what MacKinder called the Heartland and what Spykman called Rimland. This is actually something that Thucydides himself brought up, as the underlying logic of ‘commercial naval power vs agrarian land power’ was too stark to ignore, even then.

See MacKinder was kind of the first guy who to point out that hey if you look at the Eurasian continent, there’s this big really flat bit that goes all the way from Central Europe all the way to the gates of Korea. The steppe. The great expanse. The land of the Scythians and Huns. The Mongols, and yes, the Soviets.

MacKinder then points out, man the folks on the edge of this borderland have a pretty hard time once every couple of hundred years when some band of nomadic horse archers comes over the horizon ready to demand tribute. He also points out that many of the biggest wars in history were as a result of fighting over control over not only the Heartland, but the regions on the edge.

Which then leads to another guy called Spykeman who goes, wait a second, yes it is the case that every now and then someone unified the Heartland and gets all yoked up on conquest and expansion, but if you look at history, you see that what’s actually normal is that this Rimland is a lot richer and more technologically advanced than the Heartland, and that it tends to operate via defense networks of other coastal trading allies, who come together to maintain a balance of power commensurate with lots of trade and everyone getting rich (which is after all how their society is organized).

In this context, there might be a titular head of Rimland like the United States, but really it just functions as the biggest member of a team that goes all the way back to Athens and the Delian League.

Did you know the Parthenon was (kind of) the first central bank?

Turns out one of Athens first moves upon collecting tribute for common defense was to move it from Delos (hence the name Delian League) at the center of the Adriatic, and put it in the back room of the acropolis (and on Athena’s head). They needed the liquidity to promote the common defense against that despotic heartland emperor.

Sound familiar? Turns out there’s a reason the Rimland states tend to be home to the global reserve currency. You would think the home of money is in the land in which it feels the most comfortable. Which btw, goes a decent way towards explaining why a falling Britain didn’t only ally with the rising US, but actually handed it the keys to the Rimland empire.

This is also what makes the rising Axis of China-Russia-North Korea-Iran so potentially dangerous. Not only are their economies extremely complementary, Russia sends energy and minerals to China and gets manufactured goods and dual use products in return, but they create a single unified front that spans…the entire Heartland. One with enough production capacity to outweigh Rimland’s strongest power. With enough commercial and trade power to actually…threaten to replace it.

We don’t have enough time or space today to justify why we think Ray is wrong about the big one. You’ll have to trust me when we go through the 200+ data points next time, but the synthesis is simple: if Rimland can avoid getting sucked too deep into the Heartland, it usually wins, but it often has to undergo dramatic, transformational, and traumatic evolution in order to contain and defeat a rising Heartland. (This btw is where some of my more bizarre ideas for future policy come from - #NewNewDeal, Atlantic Union, 100% inheritance tax etc - the world of our children will look very different from that of our parents).

We gotta go, but for the time being put yourself in the position of anyone in this game and ask yourself, who is excited to buy bonds here? All of this sounds wildly inflationary when it finally hits, and in the meantime why not go buy a little more gold and silver to buff out the coffers in case Israel feels like calling Iran’s bluff re Hormuz or China begins to feel about Taiwan’s chips like the Japanese felt about Indonesian oil in 1941.

Not to mention the usefulness of gold in case your financial system needs the liquidity down the line and dollars aren’t for sale.

Even as an American, why am I buying bonds right now? Sure we might get a recession and the Fed might do more cuts, but at the moment, the deflationary wave looks by and large over, stocks are at the highs, and the guy promising to cut taxes and raise tariffs at the same time looks like he’s coming back to the White House. With the budget deficit running at like 7% imagine how deep Elon will have to cut to make the whole thing balance!

Till next time.

Prior Work

Disclaimers

Very thought provoking stuff. How do you think silver holds up as an inflation/geopolitcal hedge? Seems like your long-silver thesis is largely based on energy demand. Silver could benefit from what you are talking about here as well.

Bravo. Way to make it a fun read on the way to semi doom.

Seriously though, fine work! You’ve been so spot on with “you probably don’t own enough gold “ theme !