Conflict is Inflationary

Or how I learned to stop worrying about the end of Pax Americana (and buy gold)

Too much money printing causes inflation.

This is known, at least it is these days.

Too much money chasing the same amount of stuff, and in order for the market between money and stuff to clear…the price of stuff has to adjust higher.

(Note how strong this historical relationship has been and how contractionary US money supply currently is.)

What you may be less familiar with is the relationship between conflict and inflation.

Turns out when you go through the trouble of trying to find 300 years of data on inflation, a couple of things become obvious:

The vast majority of significant inflationary episodes in the developed world are a result of what you might call “Great Power Conflict”.

Emerging economies have their own inflationary spirals involving capital flight.

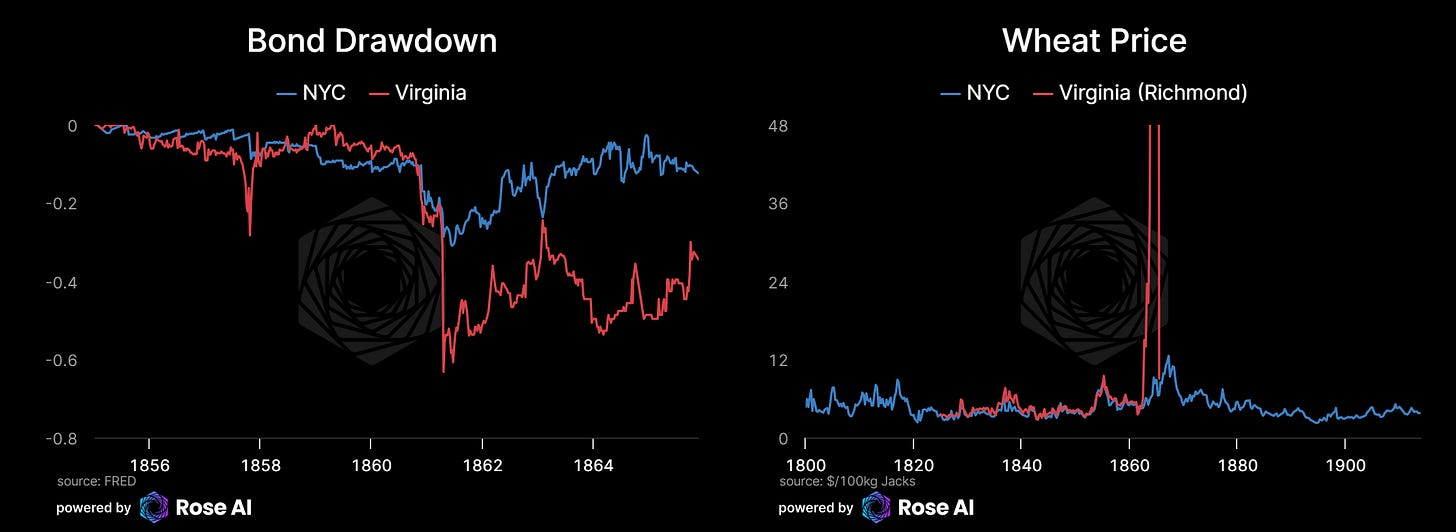

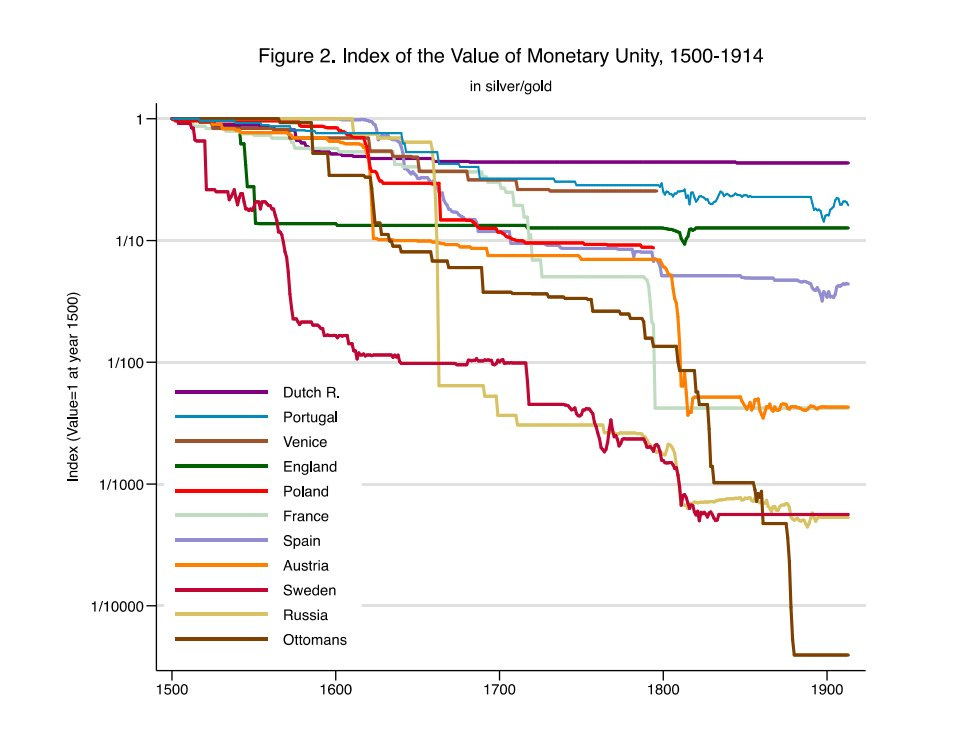

Compiling this data is difficult because data tends to start right after the death of the previous currency. Here’s are some examples:

Why might conflict cause inflation?

For starters, conflict places enormous stress on government finances. Both sides are forced to spend money or risk losing.

Losing risks being forced to default on both foreign and domestic liabilities, as you can see in the charts above. For example, the losing side in the Civil War basically got wiped out.

Even winners in major conflicts are forced to spend enormous sums to prevail. The UK by and large ‘won’ the 18th and 19th centuries, from a great powers perspective, but they spent enormous sums to do so…

…which shows up in moments they were forced to ‘suspend convertibility’ between state backed notes and shiny rocks.

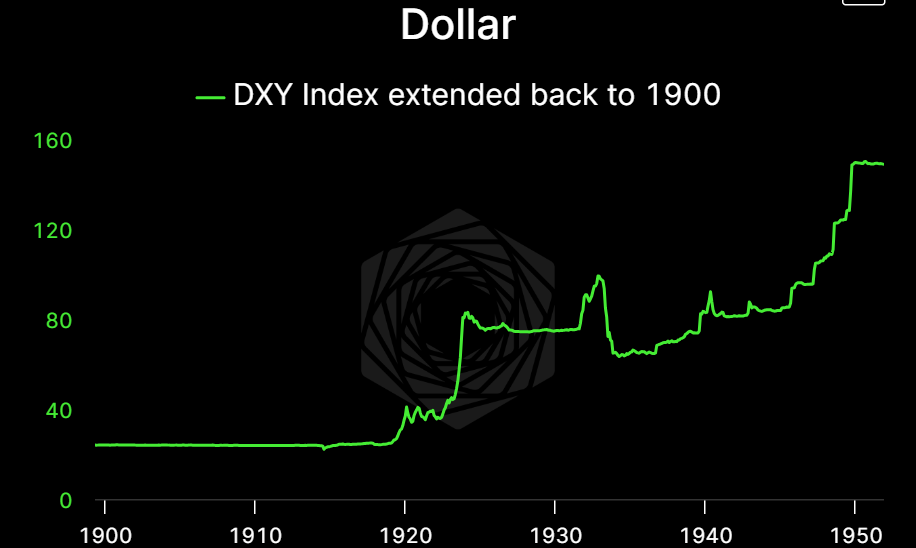

The US mostly (kinda) inherited this system, all the way up to the role as global policeman of the sea and defender of “Freedom of Navigation.” This goes all the way back to Wilson’s 14 Points and the Monroe Doctrine.

The feedback loop between conflict and inflation makes sense when you think through the economic linkages at the supply and demand level.

Conflict, particularly great power conflict, tends to create inflationary pressure via BOTH supply and demand.

During conflict, governments demand lots of food, iron and energy. As discussed earlier, this is usually being paid for with printed money. That’s an extreme version of the credit-financed demand-side shock we’re used to.

What’s important about conflict, and what makes the inflationary shocks that come from it so severe, is that these demand shocks tend to occur at the same time that supply is under attack, sometimes literally.

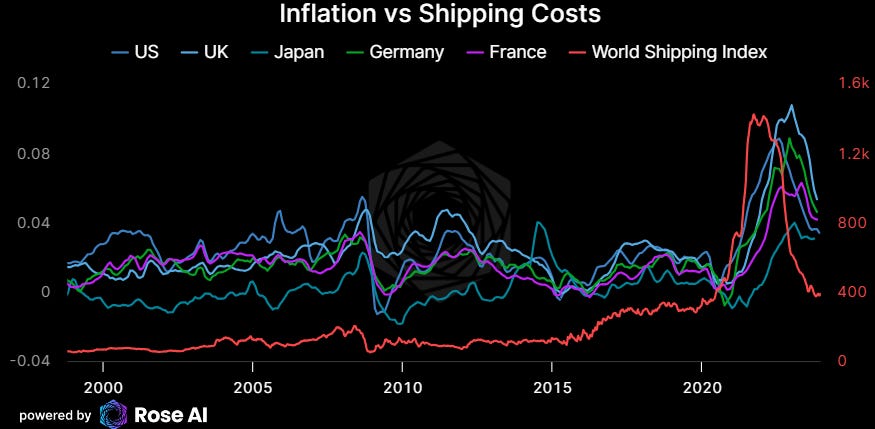

We can see this in the wake of Covid where the combination of lockdowns and inventory stocking bullwhips stressed supply chains in the same way as major conflicts.

On another level, the link between conflict and inflation checks out down to the micro scale. Conflict tends to put pressure on the supply of some critical inputs to the production and distribution of the rest of the economy.

The supply of supply.

This is particularly true for prices for energy, communications, and transportation/shipping.

The chart below shows the strong relationship between inflation in energy and inflation in transportation.

Energy is one particular good which enters into the cost curve of every other product, directly as an input and indirectly as driver of transportation and shipping costs.

Which, as an aside, is what made the 70s / Cold War so interesting.

We got the inflation of great power conflict, without the casualties.

The chart below shows the relative inflation in commodity prices in the 70s, starting with Nixon officially leaving the gold peg and then OPEC.

At this point, we can say we know a couple of things:

Conflict causes inflation by pushing up demand (via money printing) and stressing (and sometimes destroying) supply.

In the end, countries print.

The Cold War was a unique kind of great power conflict in that we got the inflation (and the tightness in energy and transportation markets), without massive direct military confrontations (though we did see a host of smaller, indirect proxy conflicts like Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan. These, by and large, were regional in nature and not directly existential to the major powers).

To some extent, the US won the Cold War via out-producing and out-competing the Soviet block over generations. Let’s call this received wisdom to be examined later.

Great power conflicts end up being bad for inflation and bonds, and good for the price of gold and the currency of the “winners.”

We appear to again be in the early innings of great power conflict. Be it Cold War II or World War III has yet to be determined.

The flare up between these two coalitions look to form broad arc along the boundary between these two spheres of influence. What Mackinder might call the border between the Heartland the Rimland.

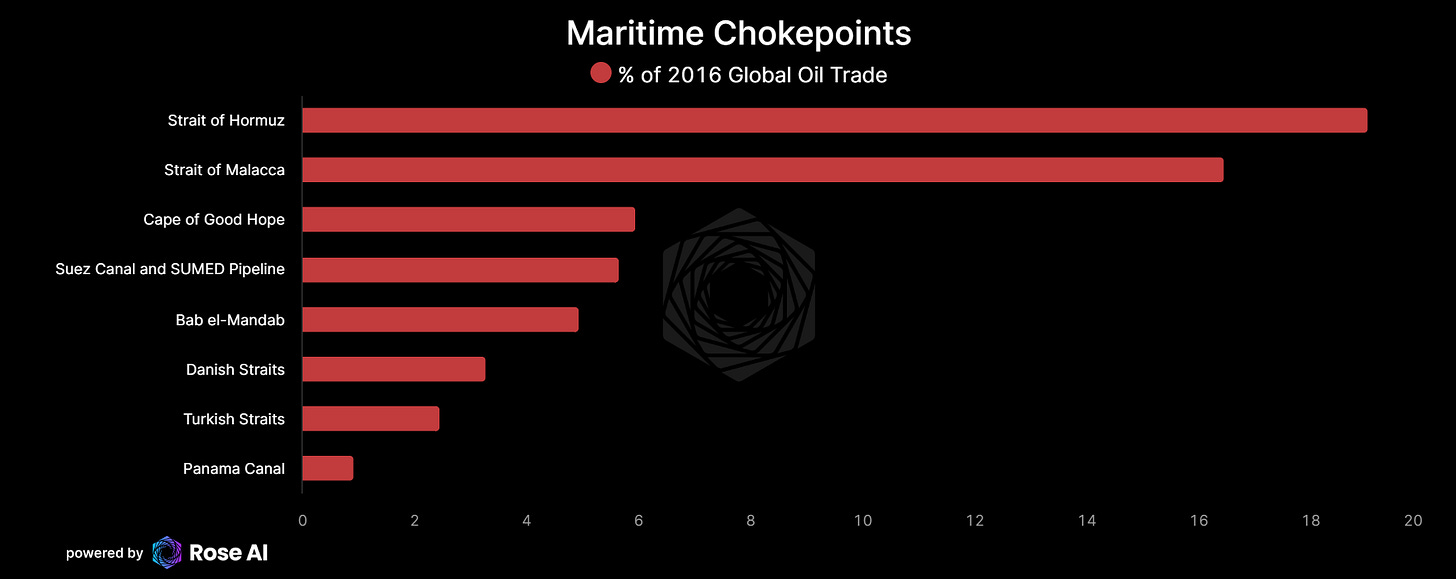

Many of these hot spots are fights over cortical commodity production and / or transportation chokepoints. Places like the straits of Taiwan, Malacca, Hormuz, and now Bab al-Mandab (the Suez). In short, the same things people have been fighting over for thousands of years.

Leading us to wonder a handful of questions:

Will the relatively muted response by energy and shipping markets to the Suez shutting down continue?

What are the odds that Iran will not only arm the Houthis to hold the Suez hostage, but extend their reach to the Strait of Hormuz?

What would the reaction of energy & transportation markets be? How much inflation would that cause?

Why does the US Navy seem mostly ineffective in building a coalition of western navies to protect freedom of navigation?

With potential problems in the Pacific, South China Sea, Persian Gulf, Suez, Black Sea, Bosphorus, Baltic, and now problems in the Caribbean, does the US have enough boats to even credibly serve as global hegemon that protects “Freedom of Navigation”?

What does a modern navy capable of doing that look like, and is there enough steel and ship making capacity (not to mention fiscal space) to catch up to the pace of Chinese building?

We’re not geopolitical experts, just macro investors trying to build portfolios robust to these kinds of uncertainties. In what follows, we’ll forward some of our more speculative musings on these topics. As we cross the breach from portfolio diversification to wild speculation, let’s be clear, the conclusion is in the title:

Conflict is inflationary.

Conflict is inflationary primarily through the combination of crazy government printing and supply shocks. When the conflict goes existential, so does the inflation.

Conflict tends to be bullish for the price of gold, energy and other basic commodities.

Conflict tends to be bearish for the price of government bonds and the currency of the losing side.

Particularly as the market prices starts to price multiple interest rate cuts into the prices for bonds, the implications are clear:

Buy gold, sell bonds.

~~~~

Recent Reflections on Conflict

February 24th, 2022

“Now we have an Axis.

Mackinder and co talked about this, Heartland vs Rimland etc, but they missed the economic angle…

If you are Athens fighting Sparta, and you lead a commercial empire, the problem is generally not your overall level of military production, but the centralization and deployment of that collective power into a single effective fighting force.

Now that axis goes from Moscow to Beijing (again), and the question becomes how long do the Ukrainians resist, how fast the CCP moves on Taiwan, and what kind of chaos erupts between the two.

And whilst those fires slowly smolder, can the Allies in Rimland (aka the West) assemble an effective coalition to counter the “new Axis” (aka the Heartland)?

Ray says that baseline military power is enough, but imho misses that the phenomenon operates at a higher level. These wars don’t end with US vs China PvP and the most number of high speed trains wins.

The UK didn’t have more soldiers than Napoleon, and it took 6 coalitions, but in the end they won.

The Hapsburg Spanish had Mexican gold and mercenaries from Switzerland, but they couldn’t dominate the Dutch into submission.

In the end Churchill mortgaged his treasured empire to the Americans, in order to beat the Kaiser (and then the Fuhrer).

And here we are again, with an old man in the white house, and a trigger happy Russian looking to relive the glory of the tank battles of ‘44.”

~~~~

December 22nd, 2023.

Two years later, we’ve learned a lot. Somewhere between Cold War 2 and a series of escalations for something more generational. Let’s review:

First an little incursion into Crimea, then a “special operation”. Something about denazification.

Looking further east, nevermind those man-made islands, just off the coast of Manila.

Defended with water cannons, lasers, and walls of steel made out of ships.

Fisticuffs on the roof of the Himalayas?

Don’t worry, no guns allowed!

A little coup in Burma, nothing to see here.

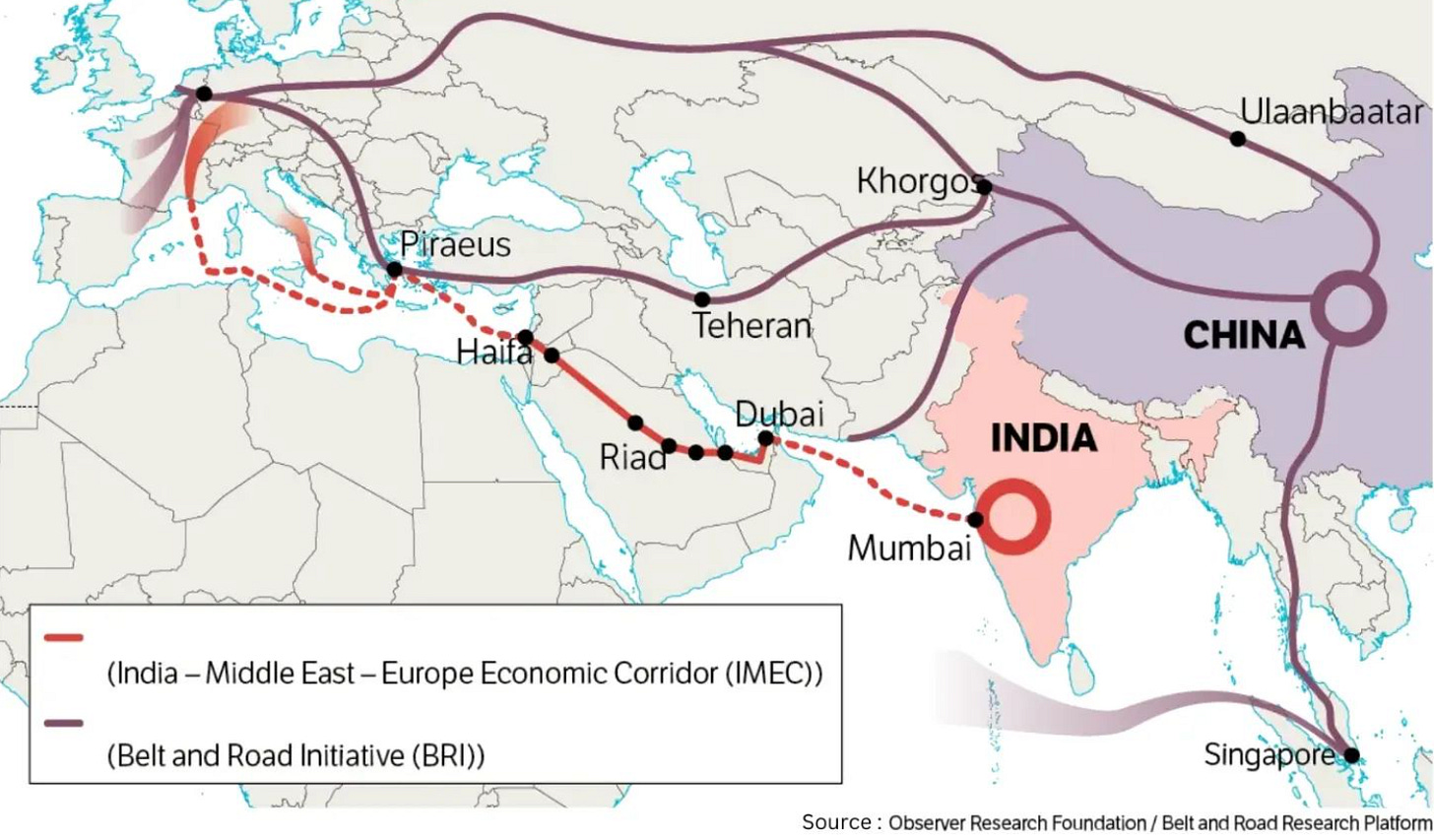

If you were China, you’d probably want a way around the Straight of Malacca.

Oh look an October surprise for Israel! Now every western city is a protest.

Say goodbye to rapprochement with the Saudis…

Along with any plans to circumvent the BRI with a road from Riad to Haifa.

Oops, there goes some underwater cables, out somewhere in the Baltic.

Turns out a Chinese ship called Newnew Polar Bear (flying a Russian flag) took it out with it’s anchor.

Which NATO article covers internet cables again?

Good news, turns out there’s oil offshore in Guyana!

Let’s send the oil to Europe to replace those Russian barrels.

Bad news, now Venezuela is threatening to annex the lot.

Something about decolonialization and a 100 year old beef between the Spanish and the Brits.

This week we learned about the Houthis cutting off the Bab al-Mandab strait.

Turns out the road to the Suez passes through their hood, and now 20% of European cargo traffic (and 30% of it’s liquified gas) is getting randomly attacked by missiles.

Everyone’s taking the long way around the Horn of Africa. Just another week and $500k-$1m more of fuel.

No wonder the Chinese are looking into nuclear powered container ships.

Meanwhile, the US tries to build another ‘coalition of the willing.’ Though so far the crew doens’t look to be rolling that deep.

Best case scenario seems to be spending $2m to shoot down $2k drones. Guess this is what they mean by ‘asymmetric’ warfare.

If the invasion of Ukraine was the starting bell of the end of Pax Americana, the direction of the new world order is clear: chaos.

To review:

Hamas as spoiler for Israeli-Saudi rapprochement (and potentially a viable challenge to BRI)

Himalayan fist fights between India and China at the top of the world.

Russo-Chinese pipeline shenanigans in the Baltics.

Serbian rumblings.

Water cannon warfare in the South China Sea.

The tightening noose around Taiwan.

Pirates in the Red Sea.

Individually, the American military could potentially deal single handedly with any one of these flash points. Together and simultaneously, we are witnessing a very real and determined campaign to slowly escalate conflict on *all fronts*, and in doing so stretch the American military industrial complex to defend everywhere and dominate nowhere all at once.

11 aircraft carriers only go so far.

Particularly when you consider what comes with it.

We’re going to need more boats.

To do that, we are going to need a lot more steel.

The latest deterioration off the coast of Yemen, where the persistent, airborne assault of global shipping by Iran-backed Houthis has forced many major shipping companies to decide they’d rather take the southern route around the horn of African. Adding a week (and about a million dollars of cost) to the journey to Europe. Note around a fifth of European container traffic and around a third of their imported jet fuel (kerosene) comes through the Suez.

Somehow, every time conflict breaks out, Europe pays the price. Literally, in the form of higher prices.

Recall European gas prices in 2022…

Conflict is Inflationary

Disclaimers

Solid work!