Dear Comrade Xi

A 5-Point Plan for Renminbi World Domination in the New World Era of the Great Rejuvenation of the Middle Kingdom

I. The Goal

Good stuff Xi.

Nice to see you finally saying the quiet part out loud. Game on.

So here’s my take. Not ironically, not as some gotcha (well kinda), but as a genuine exercise.

What would China actually need to do to make the RMB a global reserve currency?

The answer, it turns out, is a five-point plan that is conceptually straightforward, historically grounded, and politically impossible.

Which tells you everything you need to know about where the RMB’s reserve status is going.

II. What Is a Reserve Currency, Actually?

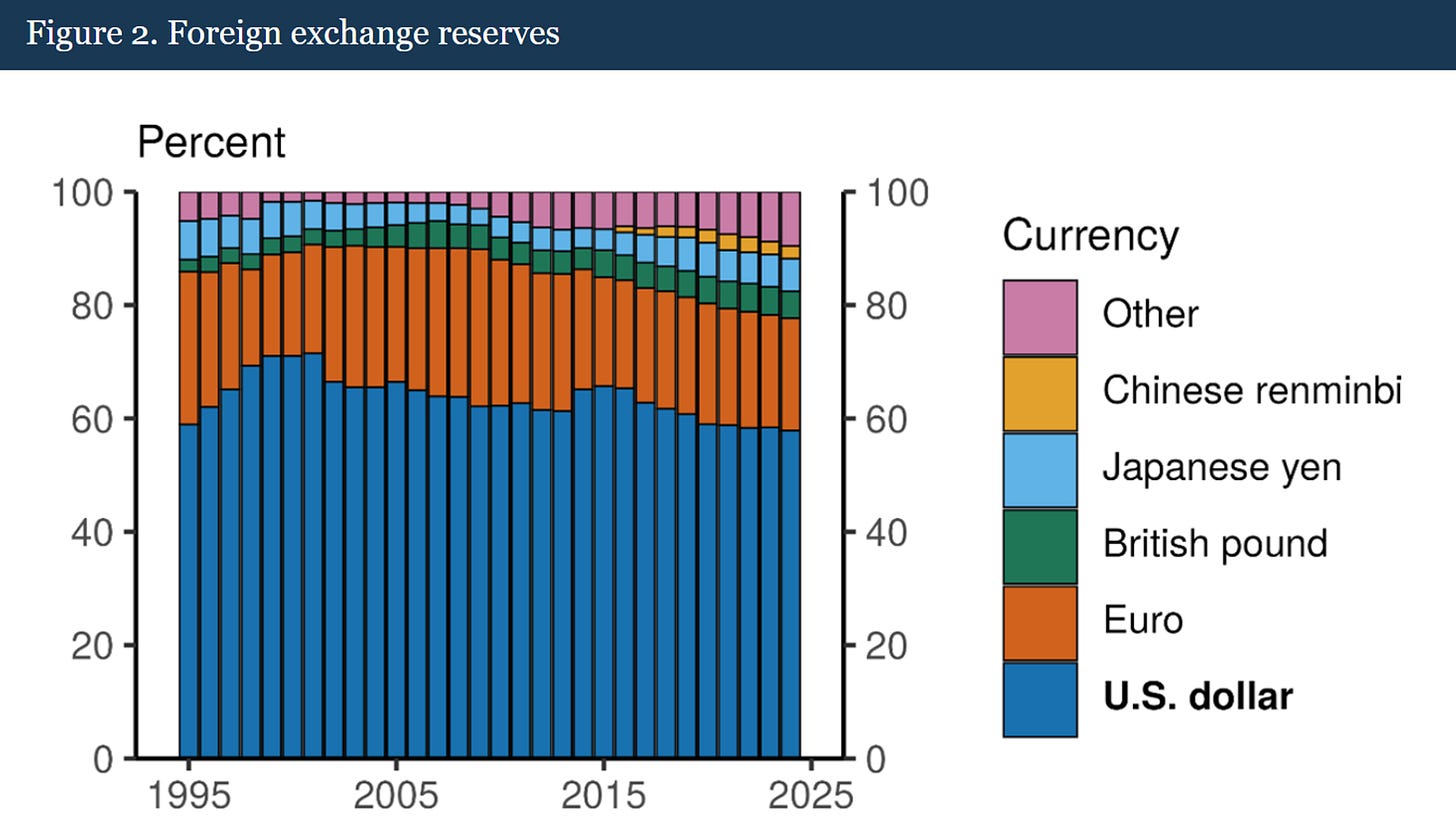

We’ve covered this in depth before (We Still Live in a World of Dollars, Dollar Doomers Missing the Point), so the short version:

A reserve currency is something that other people’s money treats as money. It’s a network effect. A Schelling point. The ultimate coordination problem.

To understand why this is so hard to displace, think about it as a chain of trust. For Joe to accept your piece of paper as money, he needs to believe Sally will accept it for her coffee. For Sally to accept it, she needs to believe Frank will take it for the beans. For Frank to accept it, he needs to know Boris will take it for the gasoline. And on and on, ad infinitum.

This is why monetary systems exhibit chaotic phase shifts in moments of stress. If any uncertainty about this chain of liquidity is introduced, the whole thing collapses, as participants choose to move to alternative means of exchange. It’s why “money-like” instruments — commercial paper, short-term debt, bank deposits, EM government bonds — exhibit runs. Recall how the failure of Lehman Brothers “broke the buck” of the commercial paper market, threatening the arteries of global capital. That’s how a single investment bank failing can suddenly make it doubtful whether American Airlines has the necessary insurance cover to fly the next day.

This chain of trust has a corollary that most people miss. You can also think of money as the thing that represents the least amount of work — conceptual, practical, logistical, legal — to settle a debt. Bank cards beat checks not because of some government mandate but because checks require pens and paper, are easily lost, harder to verify, harder to clear, and slower to clear. You could decree “we don’t trust cards anymore, go back to checks” — but the most likely consequence would be short-term compliance and the longer-term emergence of alternative payment modes.

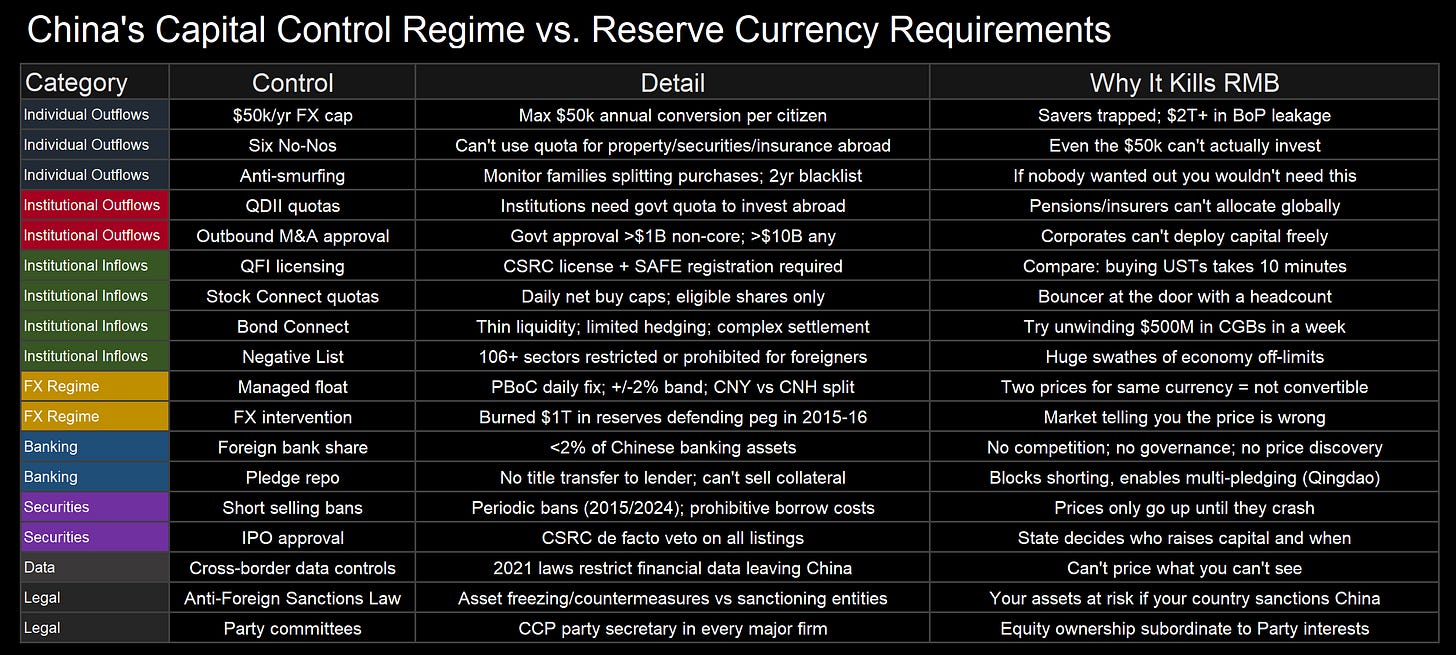

This “minimum viable work” criterion adds a fourth leg to the classic monetary criteria of store of value, unit of account, and means of exchange. And it’s the one that kills the RMB story, because the entire Chinese financial system is designed to maximize the work required to move money.

Which brings us to the deeper insight, and the real reason reserve currencies tend to live in the Rimland rather than the Heartland:

Being a reserve currency requires humility.

The humility to delegate and relinquish the power to control the direction and nature of financial transactions. The humility to let your currency circulate in institutions you don’t supervise, in jurisdictions you don’t control, in the hands of people who may use it against your interests.

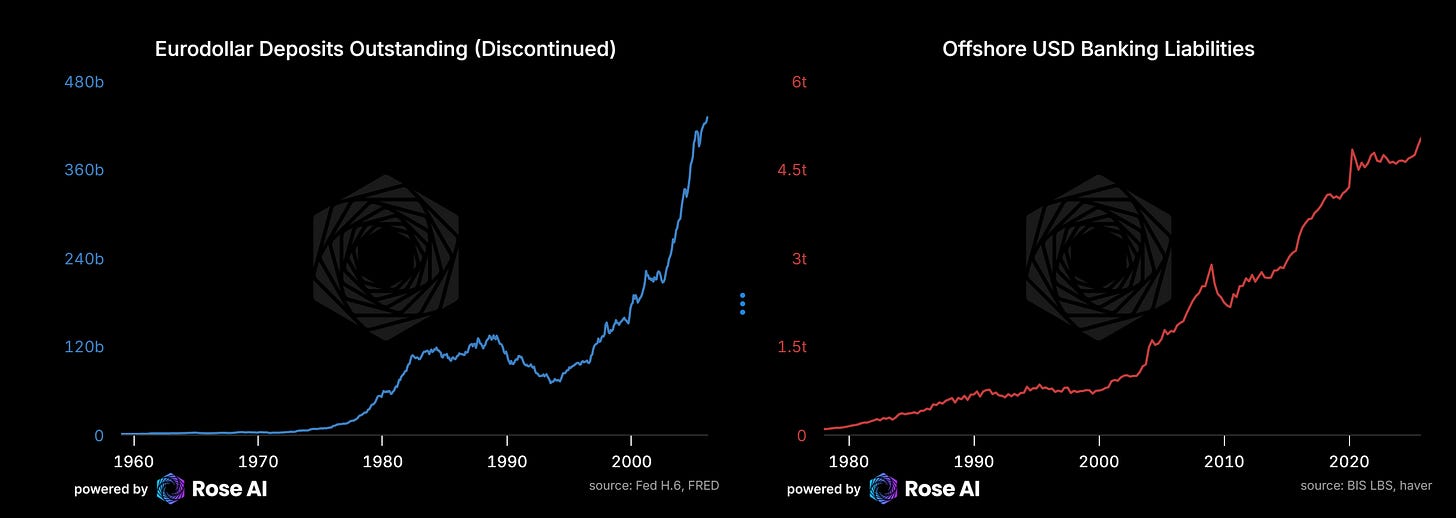

Think about the emergence of the eurodollar system in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Dollar bank accounts in banks outside the US, held by individuals outside the United States. When Gulf oil exporting surpluses were recycled into European banks, it was a reflection not of American authority but of the diffusion of American monetary power. Liabilities denominated in dollars issued by institutions outside American legal jurisdiction. Assets denominated in dollars held by investors outside America.

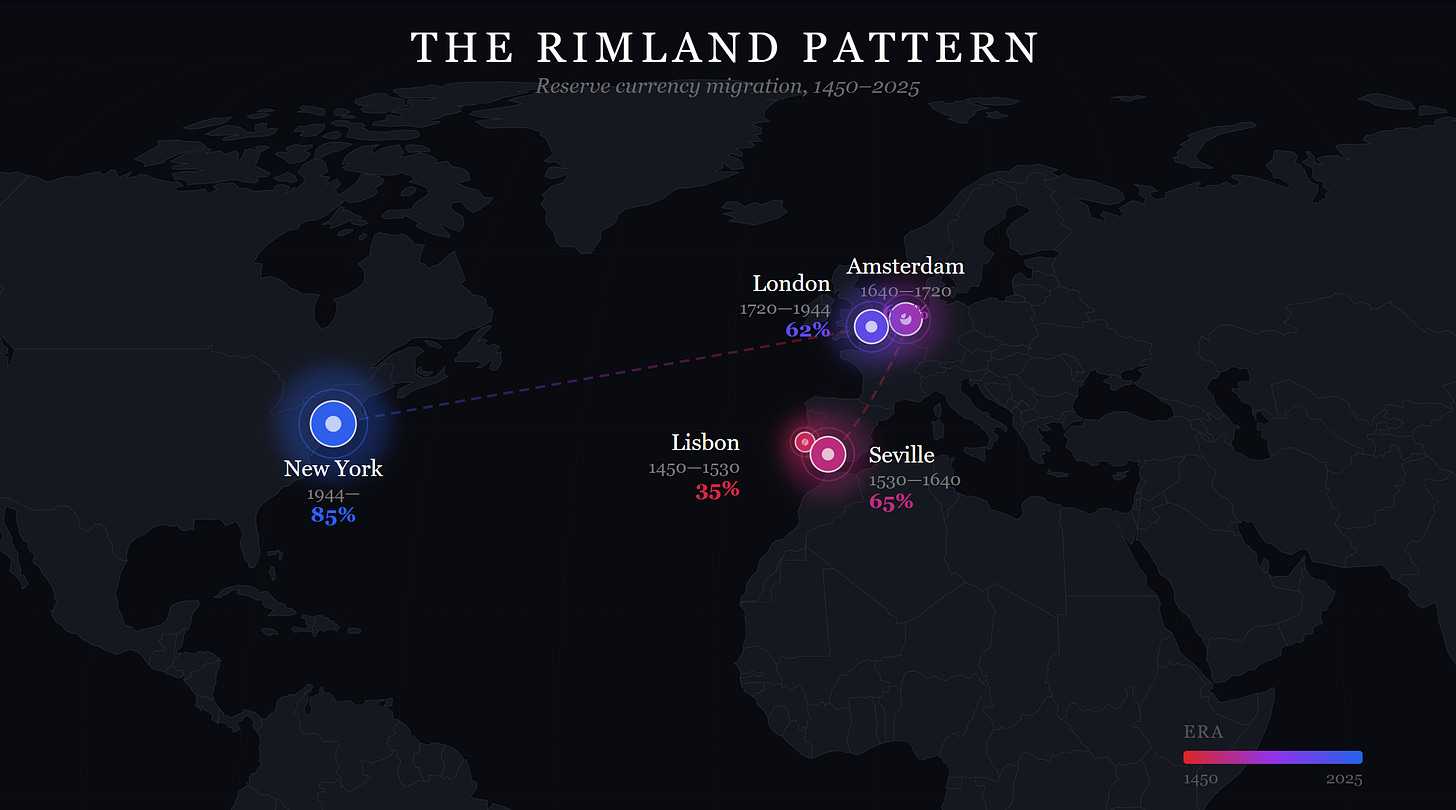

This is why, as we’ve discussed in our Rimland analysis, reserve currencies emerge from international financial centers like Amsterdam, London, New York, Hong Kong. Places where capital — both monetary and human — feels at home. Places where it feels safe. Not because the state commands it, but because the system invites it.

Now. With all of that context, here’s the plan.

III. The Five-Point Plan

1. Let Chinese Folks Get Their Money OUT

The first and most fundamental requirement. It’s also the one that makes Beijing break out in hives.

It is not enough for China — viewed as a single balance sheet — to earn more than it spends abroad.

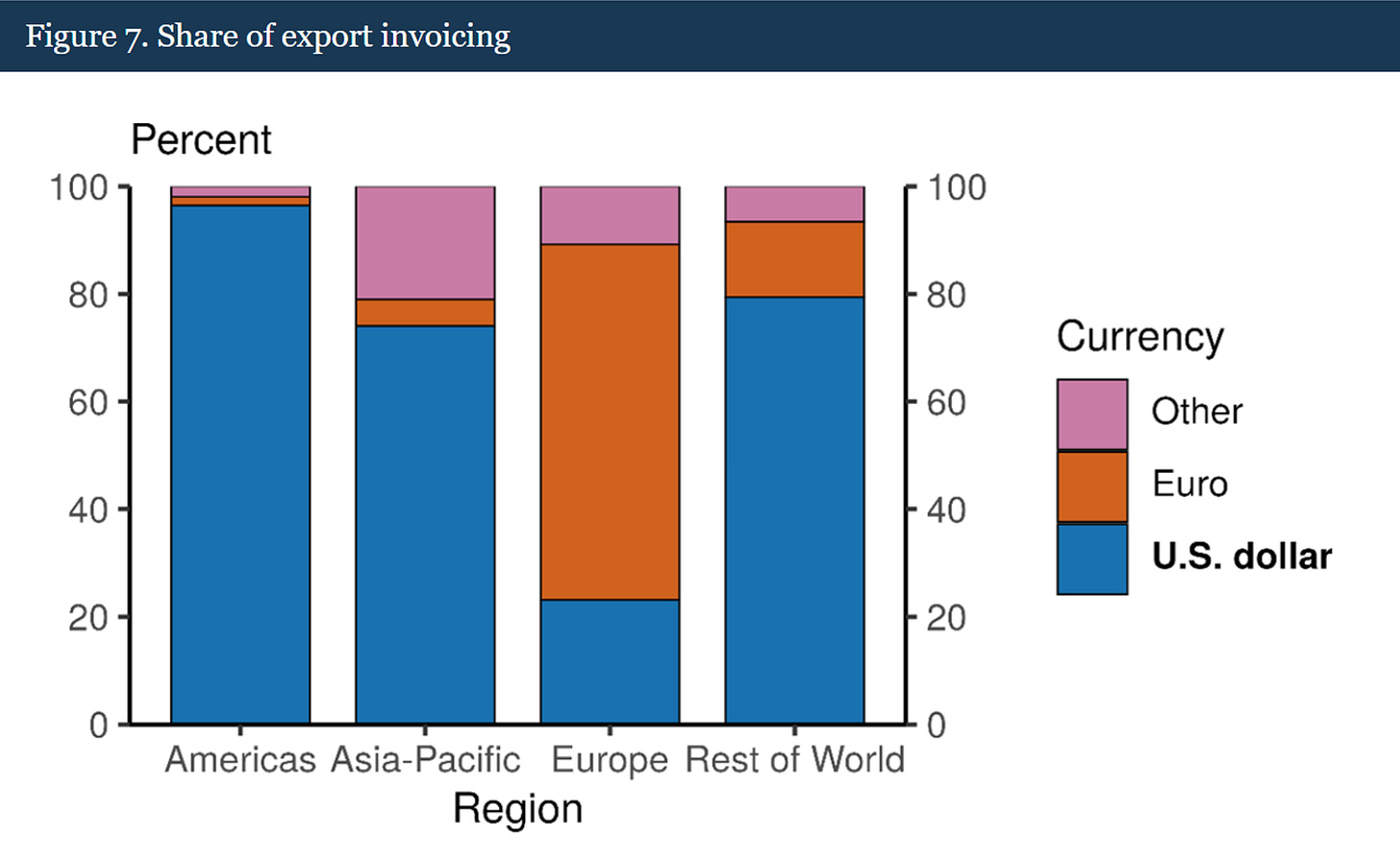

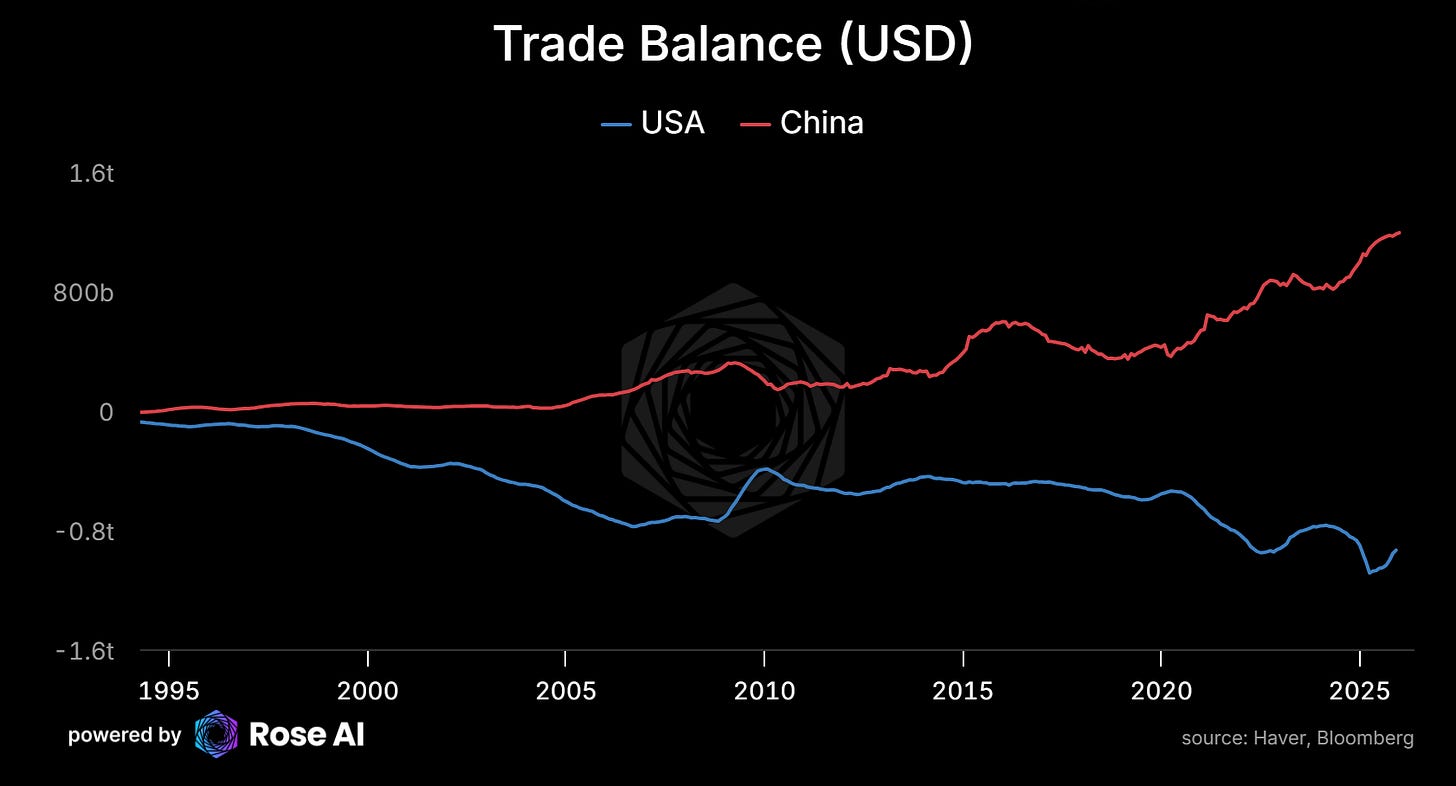

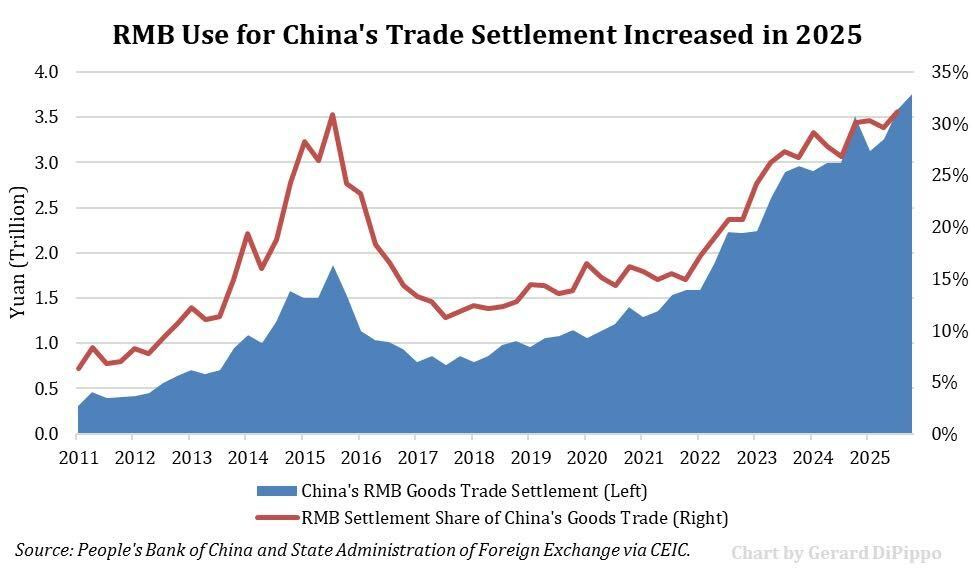

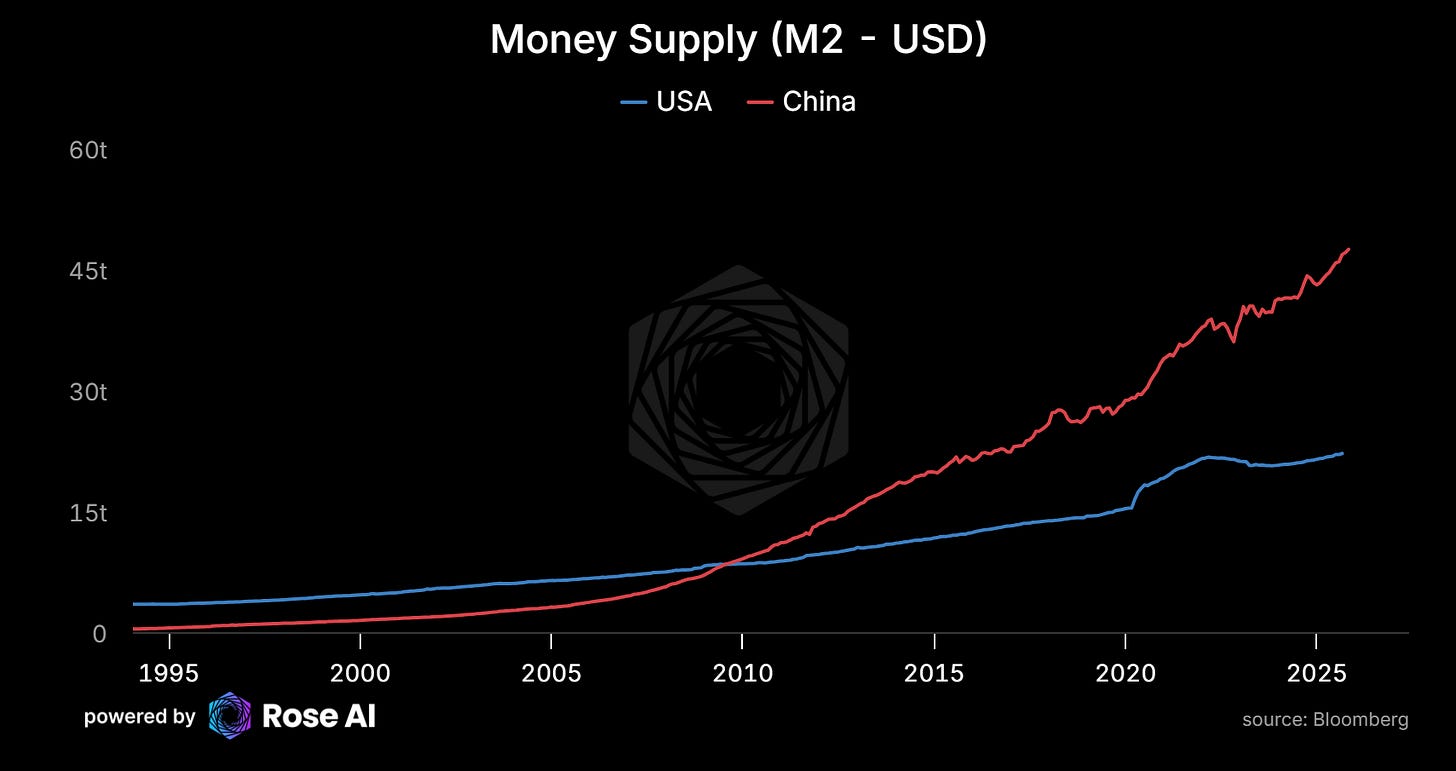

Even in spite of their best efforts, the vast majority of Chinese trade is still conducted in foreign currency, major commodity markets are still denominated in dollars, and most importantly, these foreign surpluses are not allowed to flow freely to domestic savers.

The first step in creating a global reserve currency is letting money get out.

This seems counterintuitive. Why would you encourage capital outflows when you’re trying to build monetary dominance? Because remember the coffee chain. If Sally can’t use your paper to buy gasoline for her beans, she won’t accept it for her coffee in the first place. A currency that can’t leave is a currency that nobody outside your borders wants to hold.

The catch-22 is devastating. Capital controls may make it easier to perpetuate a positive trade balance — by preventing Chinese savers from buying international goods, services, and financial assets — but they also create persistent “capital flight” pressure. The kind of pressure that has led to over $2 trillion of errors and omissions in the Chinese balance of payments, as money surreptitiously left through channels the authorities couldn’t track.

Recent efforts to massage the numbers — understating the current account surplus to reduce the balancing E&O deficit — have done a decent job hiding this from prying western eyes. But window dressing doesn’t solve the underlying problem. It just makes the eventual reckoning bigger.

This also connects directly to the stablecoin story we covered in Dollar Doomers. While Xi is talking about reserve currency status, Chinese citizens are voting with their feet — and their wallets. Tether went from $40B to $200B+ in four years, with significant growth from EM users (including Chinese) seeking dollar access through crypto rails. The grassroots are re-dollarizing even as the officials de-dollarize. That tells you something about revealed preferences.

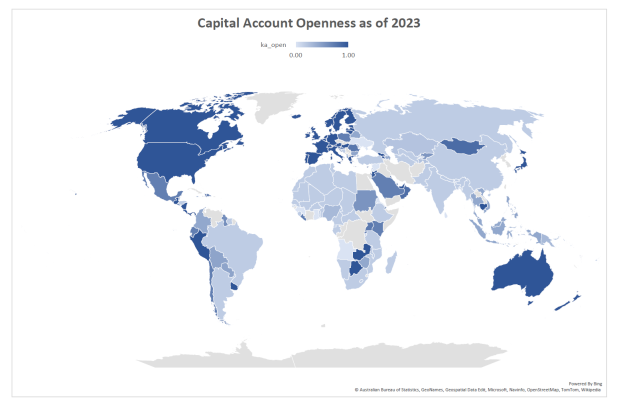

Liberalizing the capital account is the single most important threshold for this goal. And the one that most directly undermines CCP control.

2. Let Western Folks Get Their Money IN

This is the mirror image. The problem of letting domestic savers get money out is matched by China’s diligent efforts to control, restrict, and limit foreigners’ ability to get money in.

By preventing foreigners from freely buying Chinese financial assets, bank accounts, and services, they limit the two-way flow essential for reserve currency status. Take Russia as a case study. Convincing Moscow to accept RMB for oil in the wake of its exclusion from the dollar system was a genuine first step. But remember — “RMB” is just a deposit in a Chinese bank. Preventing the Russians from freely selling that deposit to another party effectively locks their asset onshore, preventing them from using it on anything outside the Chinese system.

Russia can sell its oil for RMB, but can’t sell the RMB they earn for what they actually want. Yes, they can find some domestic Chinese good to exchange it for — and China’s manufacturing base gives them a robust bazaar to choose from — but the act of preventing them from freely moving that currency to, say, Europe, where they have many other import needs, significantly reduces the optionality and liquidity of that asset. It makes RMB a worse store of value and a worse means of exchange. And it introduces additional “work” — which remember, is a critical driver of where people choose to save.

To be a reserve currency, you can’t just sell TVs. You need to sell financial assets that others want to buy. This is a massive problem. China’s domestic bond market is enormous on paper, but try actually buying and selling it as a foreign institution. The QFII system, Bond Connect, Stock Connect — each one a controlled pipe with a bouncer at the door.

3. Let Us Buy and Fix Your Banks

This is where the policy shifts move from concerning to existential.

The Chinese banking system needs to stop thinking about foreign capital — and the foreign investors behind it — as marks to be ripped off and dumb money to plug gaps. It might be fun to stick foreigners with the losses from Evergrande, but when the hole that needs filling is an order of magnitude bigger than their capacity to absorb losses, it doesn’t actually work. And it gives the game away.

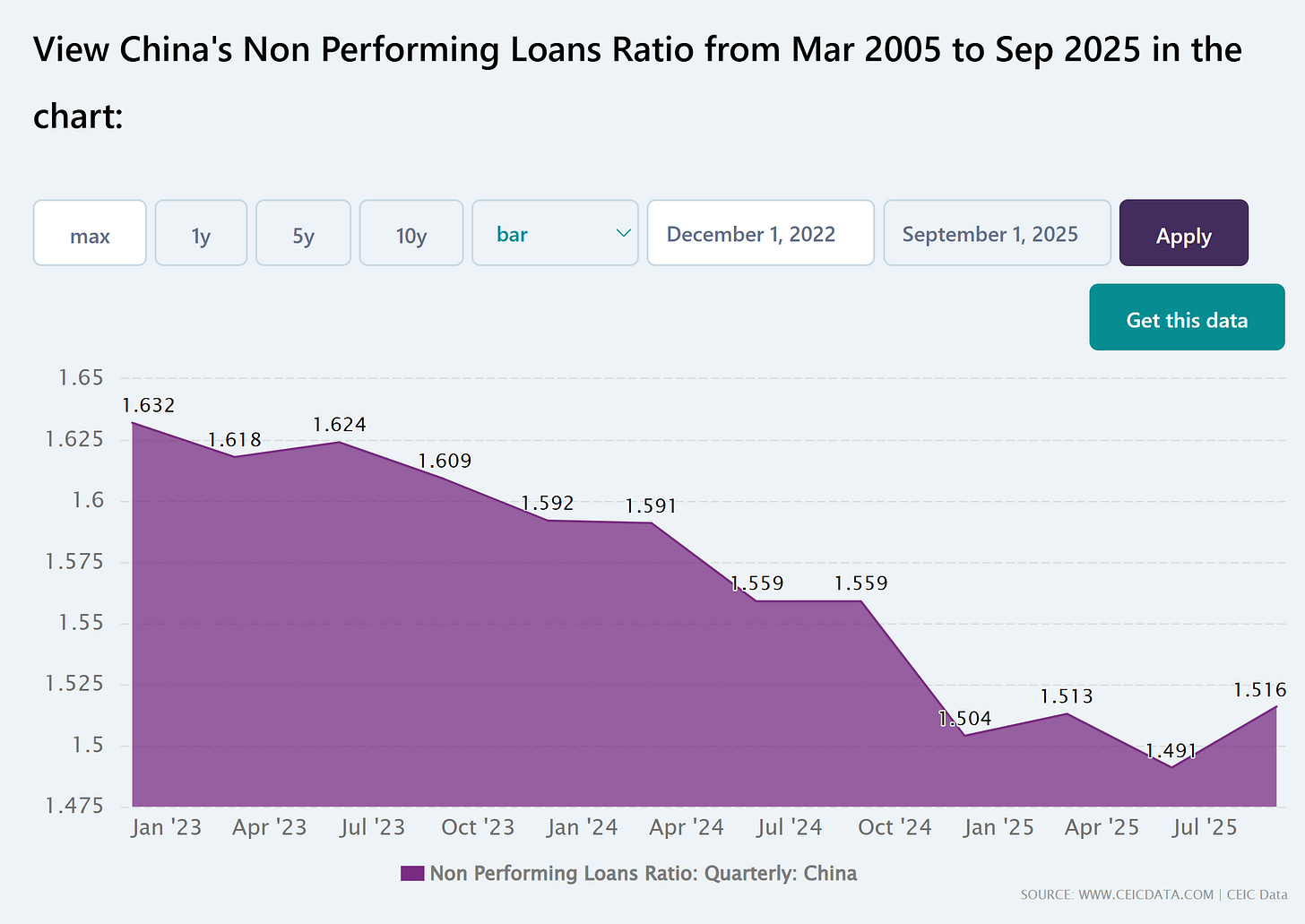

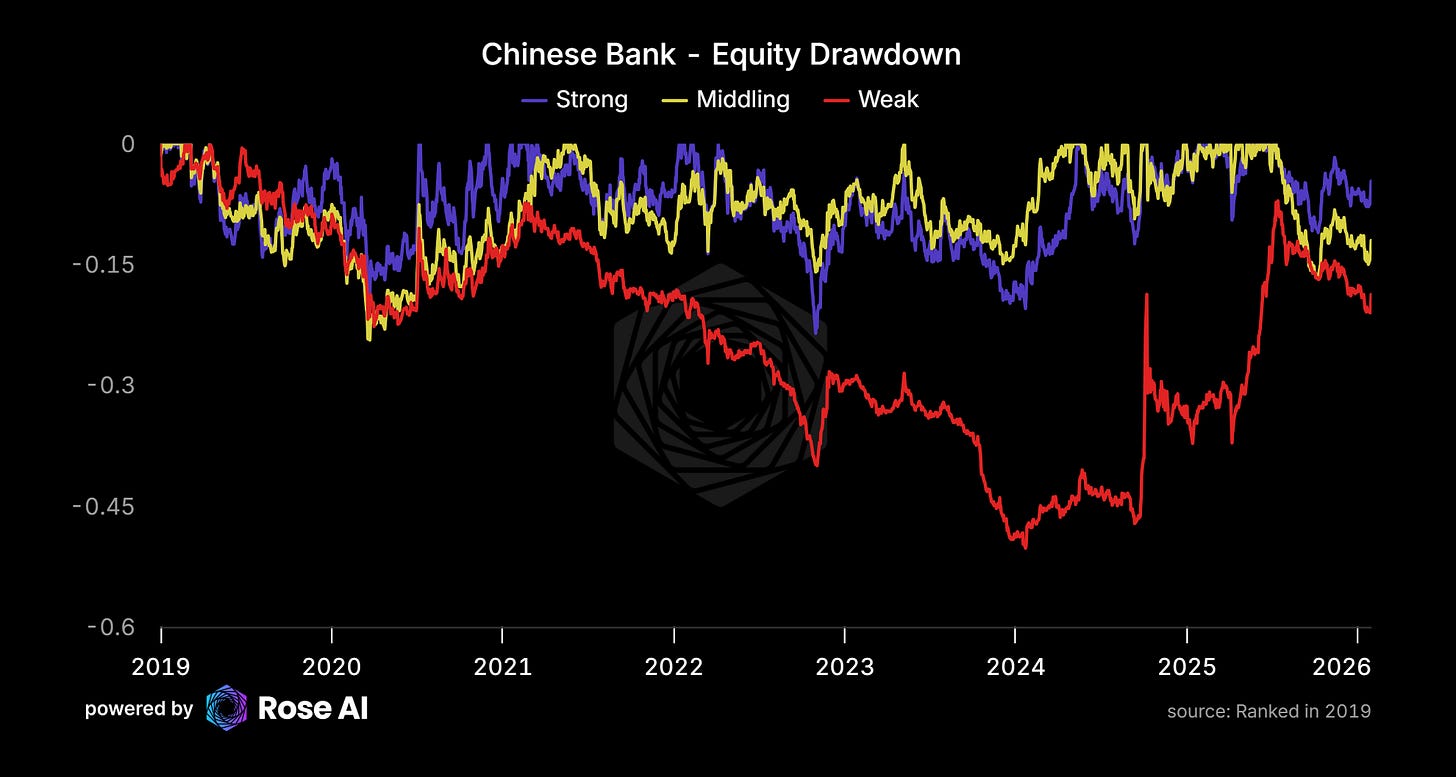

We’ve been tracking these numbers for a decade now. The property losses sitting on bank balance sheets are in the trillions. WMPs, LGFVs, trust products, the whole shadow apparatus — much of it technically insolvent. The five large state-owned banks at the core are mostly healthy, but they “channel” and “wrap” deposits into private and regional banks, which in turn invest in products with equity-like returns that promise debt-like protections. We covered this in detail in A Depression with Chinese Characteristics.

Here’s what Beijing doesn’t want to hear: over long periods of time, foreign investor control is actually a good thing for financial systems.

All those bond covenants and board meetings and shareholder votes aren’t just ego trips. They’re essential features of a functioning capital market. Because as we’ve seen in China’s own recent experience with boom-bust dynamics, management — corporate or governmental — is easily lulled into complacency in good times. The power that gets delegated to or seized by investors isn’t a bug of the capitalist system. It’s a core feature.

“If you lose money, I take away your toys and fix the machine before handing it back.”

Look at their own track record: the inability to restore rationality to the shadow banking system, to curb the excesses of the worst property developers, to guide local governments off the opium of off-balance-sheet vehicles — all of this resulting in a zombie banking system with trillions in hidden losses. This is what happens when nobody has the power or incentive to say “stop.”

Capital is actually good at fixing exactly these kinds of systems. It likes to do it. But the quid pro quo is control.

This is extremely sensitive for the Party, which has used control of the banking system — and by extension, money and credit — as a primary tool of governance since Deng’s reforms. Meaning this reform would require ceding power in the one area the CCP considers most critical to regime stability.

4. Let Campbell Short the Worst Ones

This one’s my favorite, obviously. And yes, I’m being slightly self-serving. But the logic is sound.

Nobody likes short sellers. Short sellers of banks are perhaps the most dangerous — and most reviled — of the bunch. Given the state of the Chinese banking system, with its layered structure of state banks wrapping regional banks wrapping trust products wrapping god-knows-what, the idea of foreigners profiting off the failure of local banks is politically radioactive.

But without appropriate price discovery in this system, you guarantee continued misallocation of capital. This was the lesson of 2009-2021, and it’s the lesson they’re refusing to learn now.

Think about what short selling actually does. A short seller is someone who thinks an asset is overpriced and is willing to put money on that belief. They borrow the asset, sell it, and buy it back later (hopefully cheaper). In doing so, they provide information to the market. They say: “this thing you think is worth 100 is actually worth 50, and here’s my capital behind that claim.”

Without this mechanism, you get one-way markets. Assets only go up because nobody is allowed to bet they’ll go down. Which sounds great until the accumulated mispricing detonates and takes the whole system with it. Every bubble in history has been inflated by the suppression of short selling, implicit or explicit.

The Chinese financial system desperately needs price discovery. Domestic savers need to know their money is “money good.” Foreign suppliers need to know their receivables are collectible. Foreign investors need to know their assets are real. Without addressing this, history shows you only guarantee greater misallocation, larger long-term losses, and escalating instability.

Will this force banks to acknowledge losses and bad debt? Yes. Will it lead many to come clean about capital adequacy? Yes. Will some of the weakest institutions actually fail? Yes.

But money is a fiction. A number that goes up and down. Recognizing losses doesn’t actually detract from the productivity, creativity, and strength of the Chinese people. In fact, by channeling capital away from the worst players and into the hands of the best, it would unleash the very economic dynamism that Beijing claims to want.

Will some nasty foreign speculators make money in the transition? Absolutely. That’s the price of admission. And it’s a lot cheaper than a decade of zombie banks and $5-10 trillion in unrecognized losses.

5. Move from Pledge Repo to Title Transfer Repo

This last one is weedy, but it’s the structural plumbing that makes everything else work. Bear with me — this is the kind of specific, mechanical detail that separates a functioning capital market from a Potemkin one.

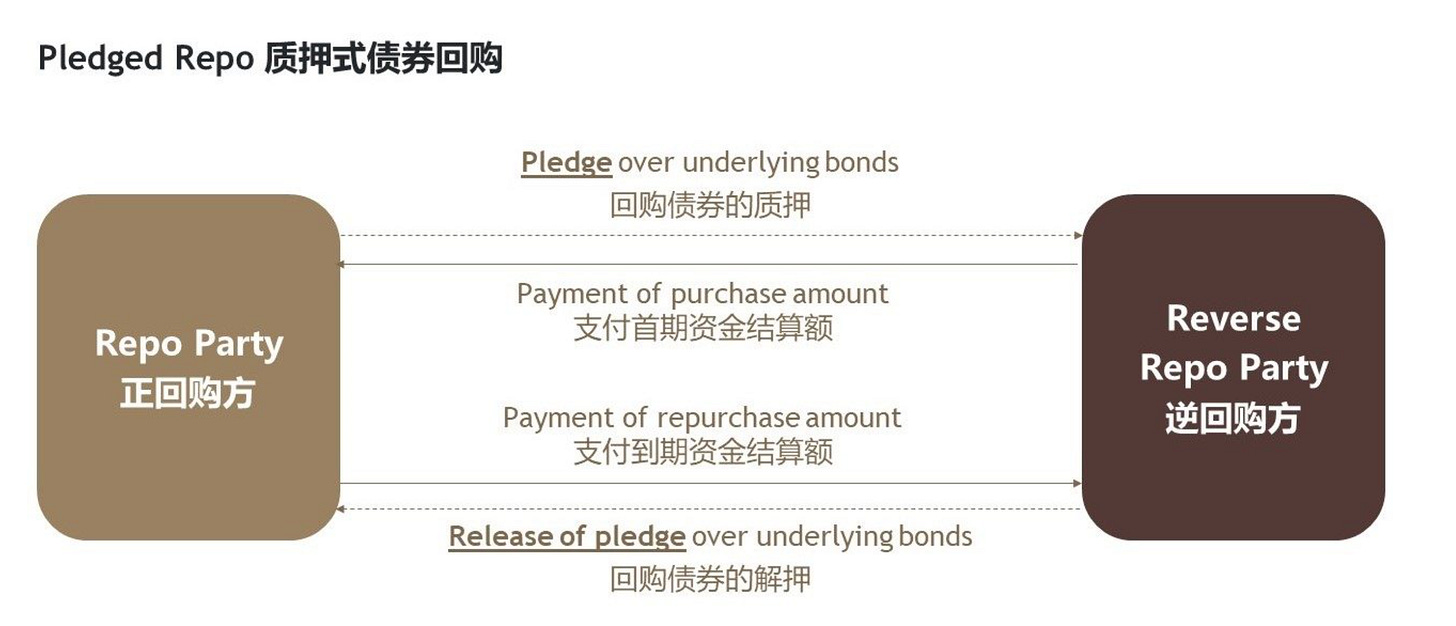

As most people don’t know, the Chinese financial system does not by and large engage in the same form of “repo agreements” as the West. In a standard Western repo, borrowing is enabled by transferring title of an asset to the lender for a fixed period of time in exchange for a fixed rate of return.

The mechanics: I give you $100 of Treasuries for a week. You give me $99 in cash against that asset. When the week is over, I give you $100 back ($99 plus $1 of interest) and you return my Treasury. If I default, you keep my collateral — protected by the fact that the amount you lent me was worth less than what you could reasonably expect from selling the asset.

This system is somewhat complex, but it enables both parties to act with full control over their respective assets. During the intervening week, I can do what I want with the cash. And crucially — here’s the part that terrifies Beijing — by transferring title to you the lender, you gain the ability to sell that asset.

For a system obsessed with control and terrified of the price discovery that selling assets provides, this is a nightmare scenario. Which is why China has predominantly practiced something called “pledge repo” — a transaction that looks like repo but is actually just another form of unsecured lending.

In pledge repo, the lender doesn’t actually gain title of the asset being borrowed against. The borrower just promises that if they default, the lender can come for the asset. No actual transfer of ownership. No ability for the lender to sell. No price discovery.

This seems clever when you’re worried about enabling short sales. By forcing lenders to accept a promise rather than actual ownership, you block their ability to sell the asset into the market. Magic.

Unfortunately, it creates cascading problems beyond the suppression of price discovery:

It adds another layer of trust in a system already drowning in opacity and potentially broken promises. Lenders must now trust not only that the borrower will repay the loan, but that they’ll be able to rapidly and effectively monetize this promise to deliver in times of stress.

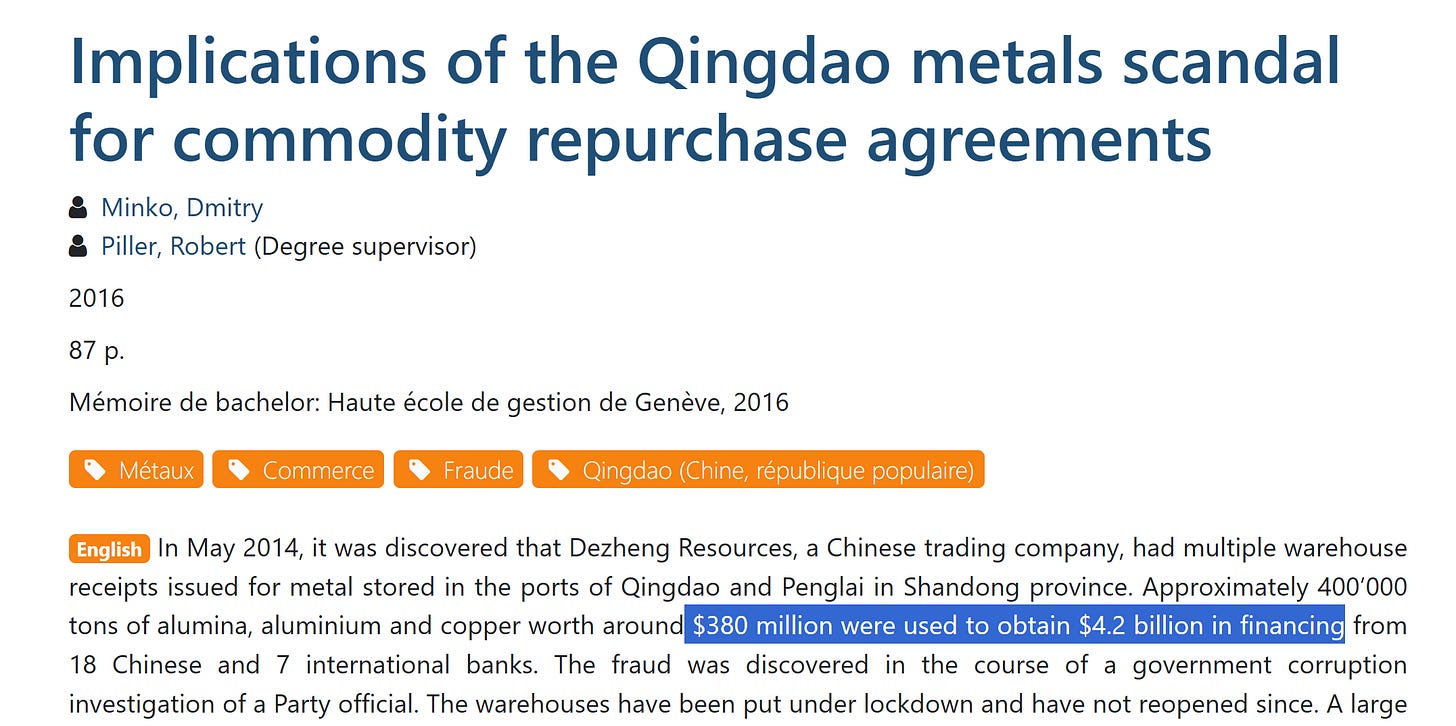

Given we’re now five years into the Evergrande saga with secured creditors still struggling to collect, the problems with this approach are self-evident.

And we’ve seen the worst-case scenario play out before. Back in 2014, when the asset in question wasn’t a piece of paper but a pile of physical commodities — copper, aluminum, sitting in warehouses in Qingdao. Not only did lenders have difficulty seizing the assets they were promised, but when it came time to collect, it turned out the same pile of collateral had been pledged multiple times to multiple lenders. The entire concept of “secured lending” had been reduced to a fiction.

Pledge repo acts as yet another layer of opium in a system that needs stimulants. It lulls both borrower and lender into a false state of confidence, supports asset prices, and protects them from the “evil” of short selling in the short run — while guaranteeing mispricing and embedded losses in the long run.

Moving to proper asset repo — where title actually transfers, where lenders can sell, where price discovery actually occurs — is the essential plumbing reform that makes steps 1-4 credible.

IV. The Punchline

So there it is. Five steps. All of them conceptually sound. All of them historically validated — this is literally what Amsterdam, London, and New York did on their way to monetary dominance. All of them well understood by anyone who’s studied the evolution of international financial centers.

And none of them will happen.

Every single step requires the CCP to cede control over the one thing it considers most essential to regime survival: the direction and allocation of domestic capital. Let money out? Lose control of savings. Let money in? Lose control of the narrative. Let foreigners fix banks? Lose control of credit allocation. Let them short? Lose control of prices. Move to real repo? Lose control of collateral.

This is the core thesis of my book: China can’t win this game because winning requires becoming something the Party can’t allow itself to be. Open. Transparent. Humble before capital. Willing to let markets deliver bad news.

The irony is exquisite. The very policies that enabled China’s manufacturing miracle — capital controls, directed lending, suppressed consumption, managed currency — are precisely the policies that prevent the RMB from becoming a reserve currency. The features and the bugs are the same thing.

Xi will no doubt be told there’s another path. Just win the big war and compel client states into compliance through force of arms, control, and dominance. This is consistent with Heartland ambitions throughout history, and in line with China’s historical conception of itself as the Middle Kingdom, central and primary under the Mandate of Heaven.

But it doesn’t work. Not because military dominance isn’t real — it is — but because it doesn’t fix the underlying mechanical problems with the financial system. Reserve currencies, in spite of the marketing, are not about power. They’re about choice. The freedom of counterparties and citizens to choose where, when, and how to transact. The safety of their property rights in a world of chaos and grift.

The United States has introduced more chaos into this calculus with the emergence of global conflict and the challenge to Pax Americana, no question. But the solution for China isn’t to match that chaos with force. It’s to out-compete it with openness.

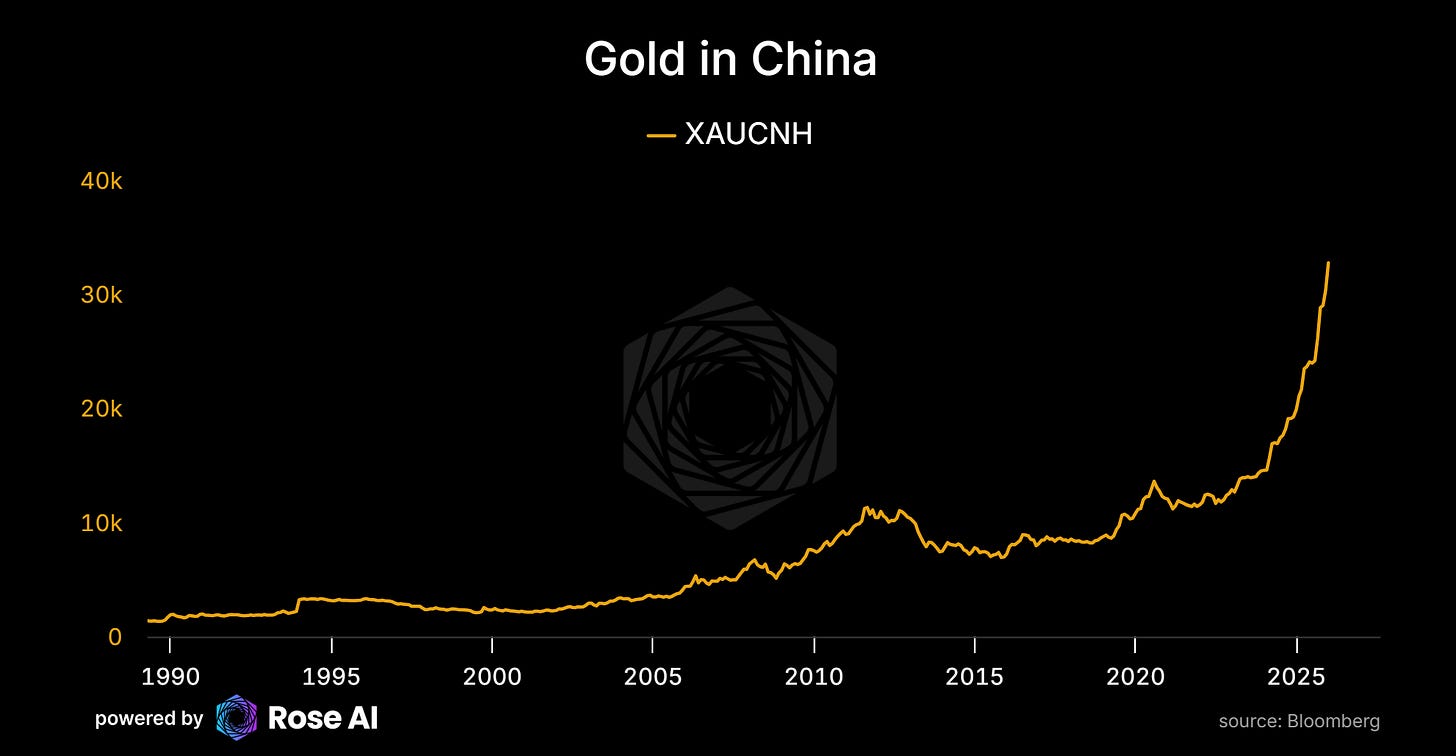

Which they won’t do. Which is why we’re long gold in China and short the RMB.

Position accordingly.

Disclaimers: Charts and graphs included in these materials are intended for educational purposes only and should not function as the sole basis for any investment decision. This letter does not constitute an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security or any other product or service by Rose, Campbell or any other third party regardless of whether such security, product or service is referenced in this brochure. Furthermore, nothing in this website is intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice and nothing in this website should be construed as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any investment or security or to engage in any investment strategy or transaction. You are solely responsible for determining whether any investment, investment strategy, security or related transaction is appropriate for you based on your personal investment objectives, financial circumstances and risk tolerance. You should consult your business advisor, attorney, or tax and accounting advisor regarding your specific business, legal or tax situation.

THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT ROSE TECHNOLOGY INVESTMENT OBJECTIVES WILL BE ACHIEVED OR THE INVESTMENT STRATEGIES WILL BE SUCCESSFUL. PAST RESULTS ARE NOT NECESSARILY INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. AN INVESTMENT IN A FUND MANAGED BY ROSE INVOLVES A HIGH DEGREE OF RISK, INCLUDING THE RISK THAT THE ENTIRE AMOUNT INVESTED IS LOST. INTERESTED PROSPECTS MUST REFER TO A FUND’S CONFIDENTIAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM FOR A DISCUSSION OF ‘CERTAIN RISK FACTORS’ AND OTHER IMPORTANT INFORMATION

These opinions are mine and mine alone and do not represent the views of any of Rose’s clients or counterparties.

Thanks for reading Campbell Ramble! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I copied one paragraph and replaced some bits. Does it sound correct ?

The Ameirican banking system (circa 2008) needs to stop thinking about foreign capital - and the foreign investors (Japan, Germany etc.) behind it - as marks to be ripped off and dumb money to plug gaps (in "AAA" rated junk MBS, CDO etc). It might be fun to stick foreigners with the losses from Countrywide mortgage (goldman's Abacus CDO etc.), but............

I hope i have not misunderstood anything. But yeah, i get that the dragon is no match for the eagle for lots of good reasons, many of which you have mentioned.

Wouldn't the US be better off if they were not the issuer of the reserve currency and still maintain open capital markets? Doesn't the reserve currency create a form of 'dutch disease' for their manufacturing sector? Or is the reserve currency status something that cannot be controlled because like you say it is a matter of trust and network effects that the US cannot control? Cheers.