Bonds vs Stocks

There Are Bonds In The Stocks: Chapter 3

Bonds vs Stocks. Stocks vs Bonds.

Every time I try to talk about something else, they pull me back in.

When I told my partner we were going to write about bonds vs stocks, they said "didn't you just write about that?"

"But, thing is, the wonderful thing about markets, is that since we've written that last piece, both the markets and the world have changed. People have exposures to both, which have changed in value, and they have forward-looking investment decisions to make. Which is kind of what makes the conversation interesting - it's a simple tradeoff which boils macro down to very simple pieces, yet is perpetually relevant."

"Ok, weirdo."

So here we are. As a reminder, when we looked into this last month, we actually decided to lift the majority of our short bond position. On the expectation that the combination of fiscal tightening and radically lower immigration would represent a disinflationary impulse. Which, when combined with a bearish outlook for stocks, led us to rotate into bonds and out of stocks, and hence buy back some of the bonds we had been short for the past five years(!).

Well, early returns on that call are clear. Not great. Stocks may have been a little too exuberant post-election indeed, but the sell-off in bonds was just underway.

Meaning, after holding the long gold and short bonds trade for ~5yrs, we may have cut the short bonds position just as it was about to truly pay off.

One of the often underappreciated pains of being early is sometimes you cut your winners too early, because you are so excited to see them finally pay. A lesson to reflect on for life as much as markets.

Anyway, so where are we now?

Well, today Ray is on the tape laying the path to bust for governments (though interestingly his framework applies as much to China as the US, though at an earlier stage, the bust/deleveraging stage), and it looks like a) tariffs are going to undershoot the extreme ‘right tail’, b) no big news on fiscal (the fight for entitlements hasn’t hit yet), and c) the reduction in immigration is real but will take time.

At the same time, our other favorite framework: conflict is inflationary has become more and more prevalent as:

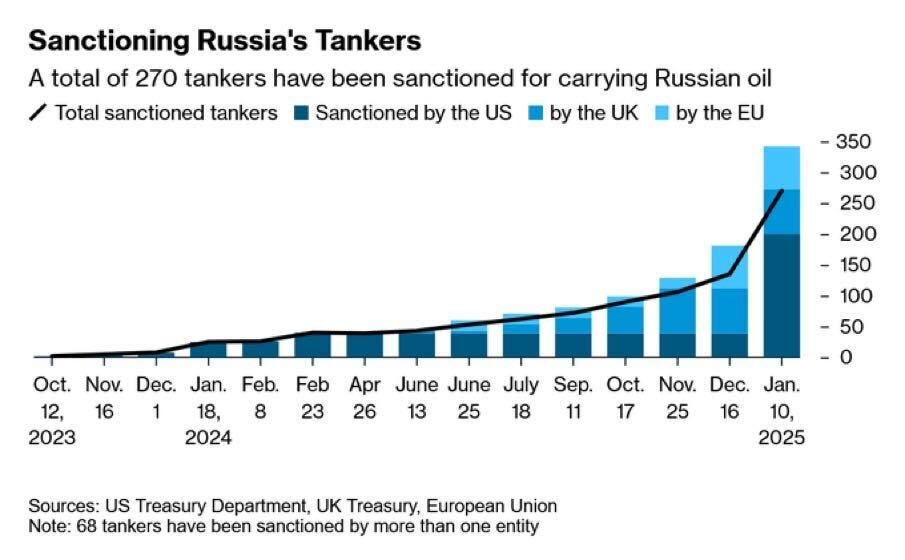

The US put in place stricter sanctions on the kinds of tankers that were shipping Russian and Iranian oil to China and India. Pushing up the price of oil (and recall, the most volatile and critical input to overall inflation is energy prices).

More undersea cables were cut and drone maker DJI announced it would stop ‘ring fencing’ it’s products from US airports.

TikTok looks like to go down to the wire (though the funniest outcome indeed would be a last minute sale to Musk/X).

A massive wildfire/arson event broke out in California, which demonstrated a lack of governance capacity to rapidly and effectively deal with the problem, resulting in somewhere between $50 and $500bn of real estate and property loss, yet to be accounted for.

All of which adds to a $35Tr pile of worry that the sustainability of the world's most important balance sheet isn't perpetually robust to fiscal profligacy. Or as Ray puts it, you need some combination of higher revenue, lower expenses, lower rates and higher inflation just to make the debt sustainable.

If we are unable to do the first two paths outlined (raise revenue and lower spending), the US will inevitably get the latter (higher inflation), which will then drag UP rates, making the debt less sustainable.

Given the general inability for governments of all kinds to get deficits in order post 2008, these are legitimate worries, even if the US role as global reserve currency mean it is much easier to finance these deficits than say, Turkey or any emerging market sovereign.

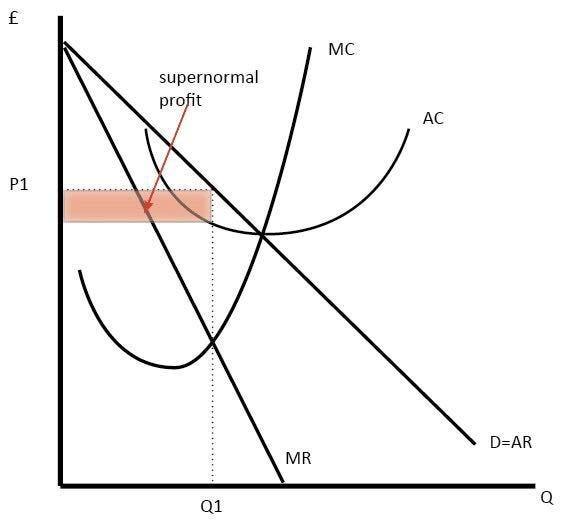

But here's where it gets interesting. Looking at the bond market, we're seeing both real yields AND break-even inflation moving higher. Not radically so, but towards the top range that’s been experienced in the past 20yrs: real yields are at post-GFC highs around 2%, while break-evens are pushing up toward 2.5%. The market is pricing both stronger growth AND higher inflation expectations.

The conventional wisdom says if inflation picks back up again or people start worrying about US debt sustainability, bond yields could go to 7%. But there's a problem with that view - it ignores the housing market which might not be able to take materially higher rates. So far things look relatively healthy, outside of the graveyard that is the refinance business (which makes sense people refinance when prevailing rates are lower than the rates at which they initially borrowed)

At current rates, we're already seeing the pressure. Push mortgage rates much higher, and you risk breaking the housing market entirely. This would hit not just construction and real estate, but consumer spending through the wealth effect. As goes growth goes stocks.

Which brings us to stocks. Stocks notionally benefit from inflation, as they represent claims on nominal profits but tend to perform best in the ‘happy middle’ where inflation is low and stable.

Partially because financial or economic volatility is directly and indirectly bad for stocks, and partially because that’s when Fed policy is the most easy and stable.

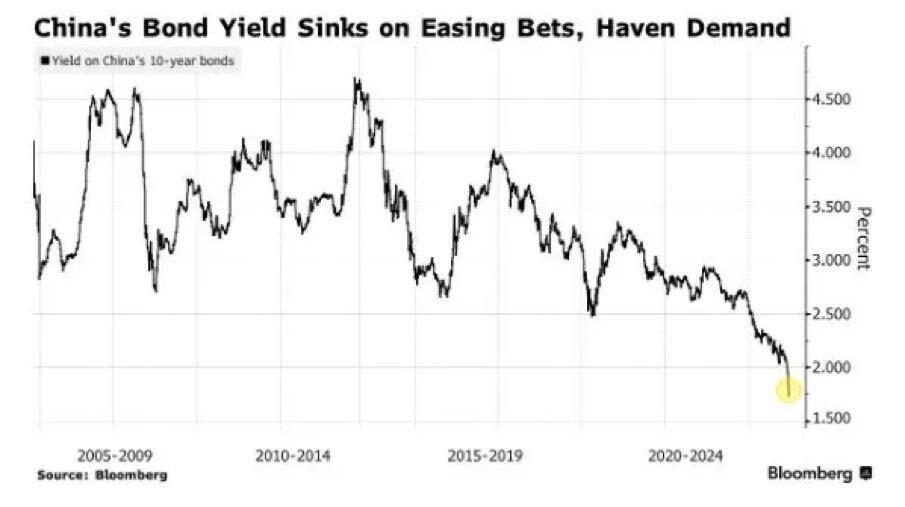

Put another way, deflationary outcomes are bad for stocks, because when we see widespread deflation, usually people are having a hard time paying their debts (hi China).

Strongly inflationary outcomes in the developed world are generally bad for stocks, because that inflation is a leading indicator for subsequent central bank tightness, which means higher rates, less asset purchases, and higher ‘risk adjusted discount rates’ to the cashflows that stocks represent a claim on.

Which brings up the central consideration when comparing bonds and stocks. The tension between the fact that bonds and stocks rally for different reasons, but in a very real way ‘there are bonds in the stocks.’

When bankers, investors, traders, and punters talk about a stock being ‘overvalued’ or ‘undervalued’ they are usually relying on a conceptual framework for valuing a stock whereby this or that stock represents a claim on a particular company. Taking aside the value from control, or status or anything non-financial.

Being only concerned with nominal returns, financiers tend to boil that value down the claim on any future profit (or residual asset value in excess of liabilities) that may come down the line, ‘discounted to today,’

That ‘discounting’ line being the hidden, but critical link between stocks and bonds.

See this concept from finance, of ‘discounting’ future cash flows to the present, is the single most important and unifying force of all finance. The idea that since all financial assets are purchasable by money, they all can be compared in apples to apples terms, in terms of how much ‘money’ they are worth today.

Since we also have this idea of the ‘time value of money’ or in normie terms ‘interest on your deposit in the bank,’ we can also try to form expectations not only of how much something unknown in the future might be worth today, but how much a fixed amount of money today will be worth in the future.

These two links, are actually two sides of the same coin. The link between how much a fixed amount of money will be worth tomorrow, is the benchmark or ‘bootstrap’ for figuring out how much an unknown amount of money in the future is worth today.

Because, if we add the idea of ‘markets’ aka the place that you and me aggregate to buy this stuff, we don’t NEED an answer to the problem of how much people expect the future cashflows to be.

Why?

Because, they are telling us their expectations for those cashflows, in the form of the price they are willing to buy or sell those future cashflows, today. We call this what the market ‘discounts’ or ‘expects.’

If you add in a third concept in the holy trinity of capitalism, that money (or more appropriately capital) is mobile, and that the market for financial assets is competitive (not true everywhere, again hi places with closed capital accounts), then you get this totally amazing, magical outcome…

Because, that formula above, the one linking the price today with the known cashflows tomorrow is what we call ‘underspecified’ when you apply it to stocks (aka you kind of have two equation and two unknowns).

The second unknown in stocks comes into the fact that due to the volatile and changing expectations for those future cashflows, investors will need to be compensated for this ‘risk’ and uncertainty, in the form of a higher rate of return (or discount rate) than what they can get ‘risk -free.’

Aka, we don’t know what Volvo’s future earnings are going to be. But we can assume that the folks who are responsible for ‘pricing’ those stocks on the margin, is comparing them not only to bonds and cash, but other ‘comparable companies.’ Comparable here in the eyes of the investor or capital not necc the biz to be clear.

Because if we assume that investor is rational (aka cares only for money, an assumption remember which is probably a simplification), then the ‘discount rate’ they apply to Volvo shouldn’t be that different than the same rate of return that investors demand for similar companies. Be that Mercedes, as another Germany auto maker, or Peugot, as a Europen producer. Or even Ford, Toyota, or other companies which look ‘economically’ a lot like Volvo. And as the distance between those investments and Volvo stock grows, we can say we know less and less about how similar their discount rate is.

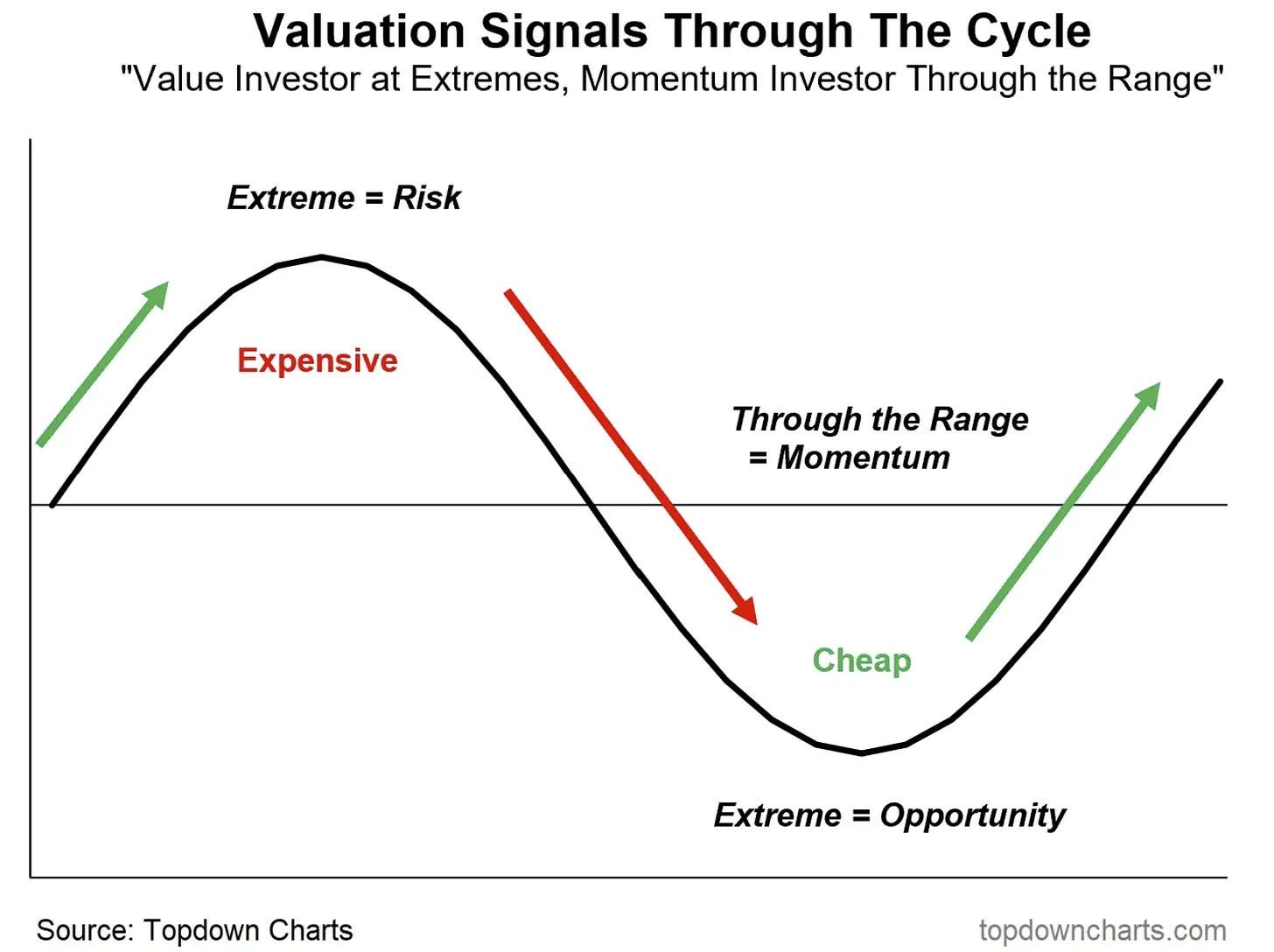

When you hear about bankers doing ‘comp’s or Tiger cubs doing “long / short'“ this is a lot of what’s happening. The Price to Earnings ratio (or Price to Sales or ‘metrics’) is an attempt to use all the various observable pieces of information out there into a single view, is this stock rich or cheap.

Ok, now that we’ve done the micro ramble on stock valuation, we can also see why government bonds going from yielding 2% to 5% might be a big deal for stocks.

Because it’s obvious that, well, when bonds are yielding 5% for 10yrs, vs 2%, then stocks have a lot more competition. This is ok if expectations for nominal earnings grows faster than the impact of that higher bond yield, to some extent normal. Which is why folks like to compare the ‘earnings yield’ of the stock market to the ‘bond yield.’

Even though they are not like for likes, they give you a sense of a) what is the ability for stocks to generate earnings/cash/profit today, and then b) how is that discounted to evolve, vs what’s happening in the bond market.

Because remember, the discount rate we apply to stocks isn’t directly linked to the risk free rate, in fact we can’t actually SEE that rate. More we assume some rate or try to estimate it via empirical observation, and then use it to try to piece out how much is this stock cheap because expectations for profit are falling vs ‘hey the guy who owns 70% of the stock just got divorced and need to liquidate, and so the market is extracting a higher return/premium for those future uncertain discounted expectations.

When we talk about ‘bubbles’ we usually talk about the inverse of this problem. Where expectations for future growth become so rosy that the asset price appreciation they create actually attracts additional sources of capital into the pool of investors. Sufficient to compress or even invert that risk premium into a risk discount. To some extent the moves around crypto and gold see this often, as they have no expected future cashflows outside of their ability to be monetized in a sale.

Anyway, which brings us back to TODAY.

Because today, we have a couple of observations/questions:

Bonds yields in the US are on the rise again, leaving many bond holders still suffering losses.

As the central risk free and collateral good asset on earth, the increase in yields in the US mechanistically pulls up rates on developed and emerging market bonds alike. We saw this in the 1800s with BoE tightening pushing up yields which then forced sovereign debt crises in the, then emerging world. We saw it again the 80s. When Volker tightened, everyone tightened, just owing to the central role in the global economy of US rates.

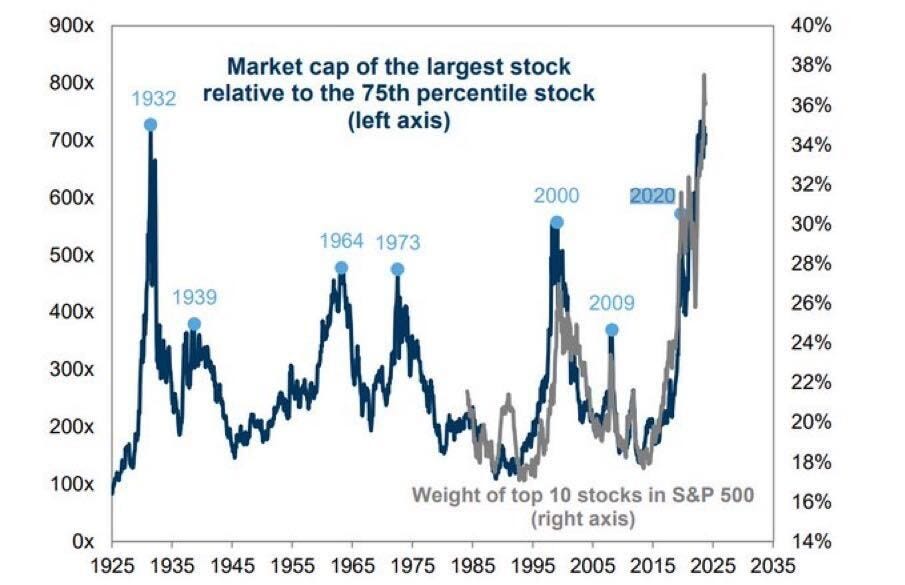

Stocks are still expensive, concentrated, crowded, and every more dependent on a smaller handful of names when it comes to generating market and economic returns. A situation which feels both extremely optimistic and extremely scary. Maybe NVidea is the most valuable company in the world because it’s the most direct play on AI, and we’re still so early. Demand for memory, bandwidth, storage capacity, energy, silver, data sets (!!!) are all going to grow as AI becomes more and more part of our daily life.

Is it really the case that the winners will be so concentrated in AI?

If it is the case that we have hit the wall of diminishing economic returns to pre-training, and that o3 is smarter than the average human but consumes $3k of energy, compute and water to do so, then we know to some extent AI will not be a pure monopoly.

Monopolies are defined by high fixed cost (check) and perpetually lower marginal costs aka increasing returns to scale. At least for now, it looks like intelligence is a) relatively easy to replicate, and b) expensive in a marginal cost sense to run, and so while there are lots of reasons to think elements of the AI supply chain will be highly monopolized (ASML, TSMC, NVidea potentially even) there are still elements like hosting, energy supply, and productization which are much closer modeled by an oligopolistic or monopolistic competition.

Is it really the case that the winners will be so concentrated in the US?

Which is why, to sum, up investing is so difficult right now. Because we have confirmation that we are on the edge of a new industrial revolution, we have a way to turn energy into intelligence. You want to be long. At the same time, bond yields are rising everyday, the Fed may actually have to hike in 2025, and the most speculative, growthy assets actually have the highest direct duration (before taking into the account the uncertainty in the cashflows or discount rates). So even if we are ‘riding the singularity’ curve, there are going to be drawdowns.

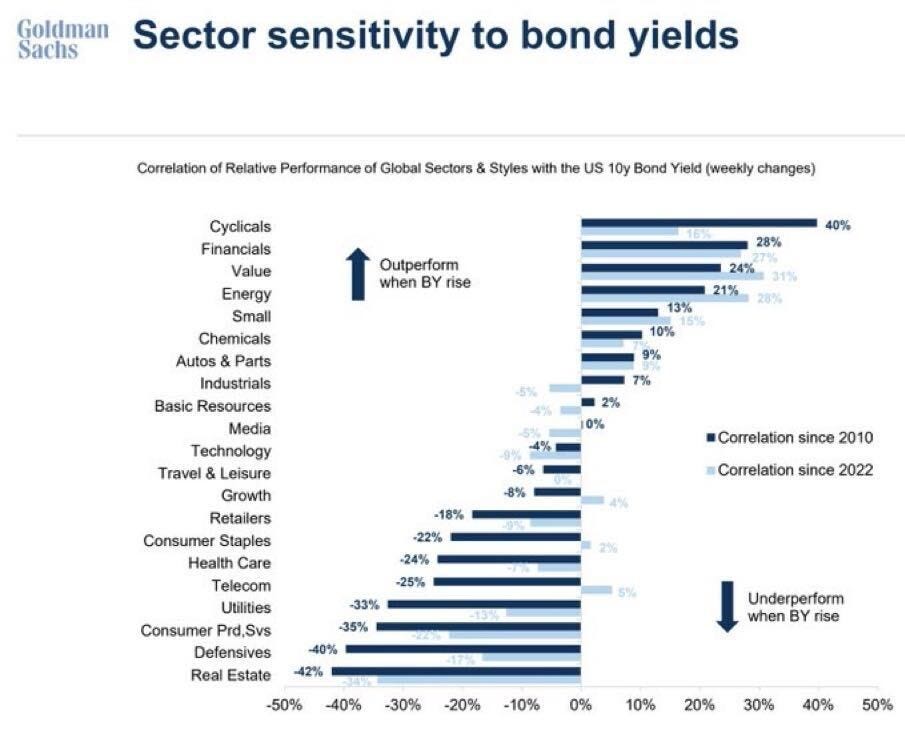

Now this logical linkage doesn’t stop folks from doing the obvious thing, and running the numbers, to find out, a level up, what happens to specific sectors when bond yields increase. Interesting that pro-growth sectors like Cyclicals, Financials and Energy at the top of the list, while Utilities, Defensives, and Real Estate (all assets more directly priced by rates) are the strongest negative relationships.

Bringing us back to today's predicament. Bond yields are rising, but they're approaching levels that could break the housing market. Stocks are concentrated in AI names that are particularly sensitive to rates through their long-duration cashflows. And both real yields and inflation expectations are moving higher.

The prudent move? Recognize that rates have a natural ceiling through the housing market channel. When people say bonds could go to 7%, they're ignoring the fact that such levels would crater housing and by extension consumer spending. The economic damage would create its own resistance to higher yields.

This creates an asymmetric setup. Bonds might sell off more near-term, but we're approaching levels where the rise in yield will start to cut into asset prices, and hence growth. And while the AI revolution is real, the current stock market concentration makes it vulnerable to any hiccup in that narrative. Maybe the play is clear, sell bonds, buy AI (and gold) and ride the waves, but for the time being, we’re cutting risk and looking for unique opportunities.

Till next time.

Question: is there also an FX channel? In other words is there a natural limit to how wide the gap between US long rates and develop market long rates can get? Is there a world in which if US is yielding 500 basis points more than Germany, the flows into treasuries would overwhelm any other factor, driving up the dollar and slowing down the economy that way?

Phenomenal post! Me thinks energy producers for data centers is the right play for AI at the moment. It will work until growth tanks, but with 7% deficit to GDP that might take a lot of time to materialize. Everyone wants this economy to run hot.