Three Green Lines

Looking for signs of a bottom in China's deleveraging ("D-Process")

I’ve been taking a lot of flak online lately for being bearish China.

Not even bearish Chinese stocks - as said last time I think you should be out of them unless you are looking for ‘chaos beta’ - but more so holding what I believe to be the three ‘green lines' that would actually form a sustainable bottom in their ugly deleveraging. The needed medicine to transition to what Ray and Bob would call a ‘beautiful deleveraging.’

These 'three green lines' represent the key questions about money that Chinese policymakers must answer to establish a market bottom.

Who takes the loss and how much?

What’s up with the bank recap?

Helicopter Money? When, how much, how fast?

At the moment, these questions remain unanswered, and the volatility in China's equity market looks more like a bubble popping than the start of a new bull market.

Like, I can’t emphasize enough how weird it is for stocks and vol to be surging at the same time. Usually these things move in opposite directions. Usually vol surges when stocks are in a drawdown, and bottoms are built first with a decline in realized volatility.

This is by and large how the Chinese market functioned until about a month ago. When we saw this atypical surge not only in stocks, but the whipsaw up down up down that leads to what we call ‘realized vol.’

This week we saw record outflows from Chinese stocks (after about a month of record inflows). I can’t help but believe it’s because these questions still remain by and large unanswered to everyone, not just me…

Below I’ll go through where we look to be in this movie, but as always look to “Gold in China” as the valve here while these questions remain unanswered.

Who takes the loss and how much?

The first step to answering this question is to look for where policymakers draw the line on what liabilities they are willing to guarantee or ‘bailout.’ Recall there are around 100bn square feet of real estate currently under construction in China.

Somewhere between $5t and $25t of floor space, depending on how deep the bubble penetrated past the tier 1 cities into the hinterlands.

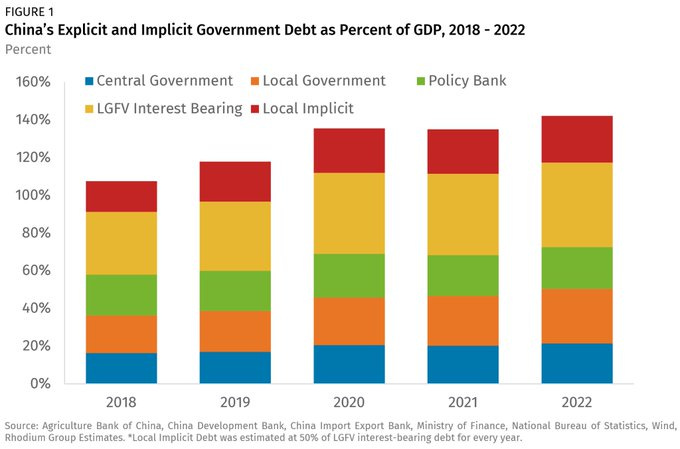

Currently, the policy appears to focus on bailing out insolvent off-balance sheet 'Local Government Financing Vehicles' (LGFVs). This is good, especially if it represents a signal from the government that all $10tr will be brought on balance sheet.

The concerning aspects are twofold: the bailouts are coming from local governments themselves, and the amount represents less than 2% of the total LGFV debt.

Which means yes we are closer to nationalization of this debt by the much stronger central government balance sheet, but for the time being they intend to slowly rotate bring the LGFV debt on balance sheet for local governments already weakened by the decline in property demand (they get a lot of their budget from land sales).

This move is by and large expected and was always part of the willingness from lenders to extend credit to local projects. However note that interestingly the move will not explicitly increase the central government’s debt load. Meaning in a sense more creative accounting or ‘maintain appearances.’ Look for this whack-a-mole behavior to continue until the creditors force the central government to explicitly step in. Also note $140bn is a drop in the bucket compared to the amount of LGFV debt outstanding (~$10tr), so another issue where the direction is right but the order of magnitude is off.

What is a bit less than expectations is any clarity on what happens to a) failed shadow banks / trusts / financial intermediaries, or b) property companies and other over-levered borrowers. Meaning, yes LGFV holders have been bailed out, but that was always going to be the case, what about the banks?

What’s up with the bank recaps?

What is the process by which failed lenders will be resolved/recapped/bailed out?

Given there will be some loss that flows through from borrowers to lenders, and given the overall lack of capital in the Chinese banking system, we continue to believe some form of recapitalization + bad debt disposal is a necessary condition for a bottom in the Chinese deleveraging.

This isn’t a controversial view, in fact it’s basically consensus. Yet, no one presses the issue in the face of good news about stimmies.

If LGFVs were the only problem on bank balance sheets, then nationalizing or bailing them out would resolve the crisis. However, LGFVs represent just one-third of the problem. Another third consists of bad debt from property developers, shadow banks and other real estate linked sectors. The final third comprises loans to potentially insolvent companies.

What’s been the plan thus far? Well first we got a tiny $40bn of capital announced followed up with a plan to inject another 1tr RMB ($140bn) to the state banks in the form of co-cos (loss absorbing bonds). This is smart! It increases the loss-absorption capacity for the biggest firms and increases the ability for the “national team” to put in national service when time comes to resolve these bad banks. This is a mechanism that has already been established, yet seldom used.

Folks who recall failed bank like Boashang, Jinzhou or Shengjing may be familiar with this process.

But where are other bad banks? How can policymakers find them when there’s no transparent market for their equity (true for much of the local or regional banks) or their liabilities (remember when data vendor WIND got in trouble for reporting the yields on Chinese bonds?)

What about all the ones that have been known to be bad for years? What’s the plan here? Thusfar, even with the policyshift to easing, we see more focus on ‘maintaining appearances’ than actually identifying and solving the problem.

Further, once we get an answer to question #1: “Who takes the loss?”, we can start to pencil in how much.

Meaning we can start to do the math of how much new capital the banks really they need, not just how much can we quickly spin up in Co-Cos.

Someone is paying attention here, but it needs to be done quickly and smoothly before financial contagion breaks out. This is the critical step and the clock is ticking.

Helicopter Money, When?

Initially there was a lot of noise about fiscal with big numbers (in CNY), but the market was disappointed to learn were announcements of existing policies or facilities that have already been ‘baked into the cake.’

At this point, outside of some increased welfare benefits, details on what kind of fiscal expansion will be forthcoming.

Recognize that the old model of stimulation via excess investment is no longer available to them. Previously the the government would announce higher targets, instruct (via “window guidance”) the banks to boost funding to the LGFVs/shadow banks. This investment funding turned into spending in the economy, as these infrastructure and real estate projects - once financed - would go into the market and suck of labor and materials to follow through on their promises.

Which, when put in context, puts the dilemma facing Chinese policymakers in stark contrast. The old model is broken. What they are comfortable doing, hitting the big red investment/credit/debt button not only won’t work, it’s part of the problem. That means they need to work through new ways to directly stimulate household spending, ideally by way of central government financed support to incomes, what Ben Bernanke called “Helicopter Money.”

There is even regional precedent for this transition from an investment and export economy into a consumer economy: South Korea. When the South Korean growth model stopped working in the late 90s, they actively sent credit cards to Korean households to stimulate demand.

While this led relatively quickly to a household credit crisis (and then another mini deleveraging in the early 2000s) it also marked a successful transition into a more consumption oriented economy. Potentially concerning to mainland policymakers it also led to a marked cultural shift in South Korea towards more materialist western values. Or at least that’s the rap.

Waiting for Godot or Waiting for a Five Step Process

Some might say I’m overly biased against China after almost a decade of warning about the long term unsustainability of their growth model and financial system, but to me answering these questions is essential to resolving any bubble, let alone one in the biggest asset class in the world.

You might even say these set of questions are a practical application of a framework on how to solve important problems. Call it the five step process boiled down into three:

Identify and diagnose the problem. Accept the old growth model is dead and zombies are bad for business. “Where is the line?” Thus far policymakers appear unable to actually identify the root of the problem - insolvent real estate borrowers leading to insolvent banks.

Design a solution based on that diagnosis. Translate where that the line is (on the debt side) to the likely systemic pain felt and hence the magnitude of the bail out / recap required. Thus far we’ve seen hints at the direction of motion, but most recaps have been off by an order of magnitude.

Implement solutions. What are the pipes, and how much and how fast are they going to be turned on? Will the central government actually directly stimulate or will it continue to rely on old news and an alphabet soup of off balance sheet borrowers and vehicles to hide the amount of debt the central government really in on the hook for. Simplifying this and being clear on the amount, timing and process for Helicopter Money would be the last step here.

Next time we come back to this topic we’ll talk about what’s happened with asset markets and the economy since the policy pivot. We’ll also update our picture “Gold in China.” Where, as predicted, both public and private players have shifted from US bonds to purchases of gold and silver.

Lastly we’ll cover where you might want to be positioned in other assets, depending on your view of how this whole thing plays out. Hint: if they really do restart the animal spirits and diagnose and implement a fix to the broken banks, then you probably don’t want to be long their government bonds, or anyone else’s!

Till next time.

Disclaimers

really profound insights

Killer analysis