The Unicorn Economy: The Great Liquidity Drought

An investigation into the "Series A Crunch"

Eight years ago, I wrote a (rather long) piece called the Unicorn Economy. The core argument of the piece was a relatively simple concept, but one that a lot of folks had good reason to ignore at the time:

The Unicorn Economy runs on ZIRP.

Rates were ~zero, meaning Net Present Values (NPVs) were high.

When rates went up (because of inflation, China selling bonds, or both), startup valuations would go down.

Today we’re going to revisit this framework in the context of what’s happened with tech and monetary policy over the intervening 8 years. We’ll see how covid (and the expansionary monetary policy in its wake) kicked this process into overdrive on multiple levels (funding, valuations, revenue, and even behavioral change).

We’ll then revisit the first order impact of Powell’s tightening on the Unicorn Economy. First in the bond markets, then, as predicted, in the form of lower valuations for tech companies. This, when combined with lower IPO and M&A activity (thanks Adobe vs Figma!), has meant less liquidity for the funds and the LPs that launched a million startups in 2021

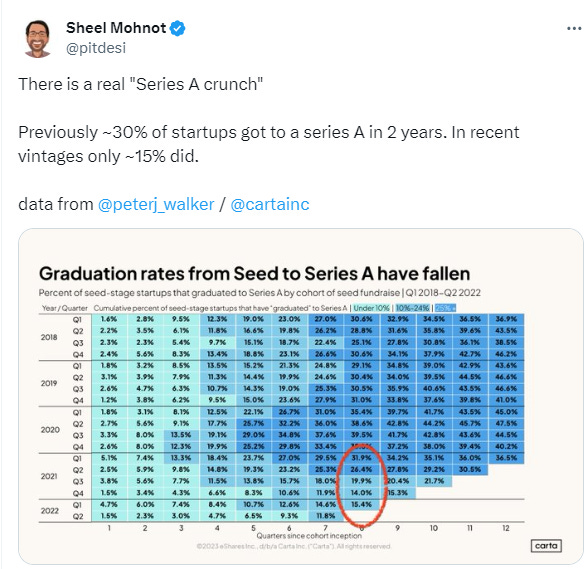

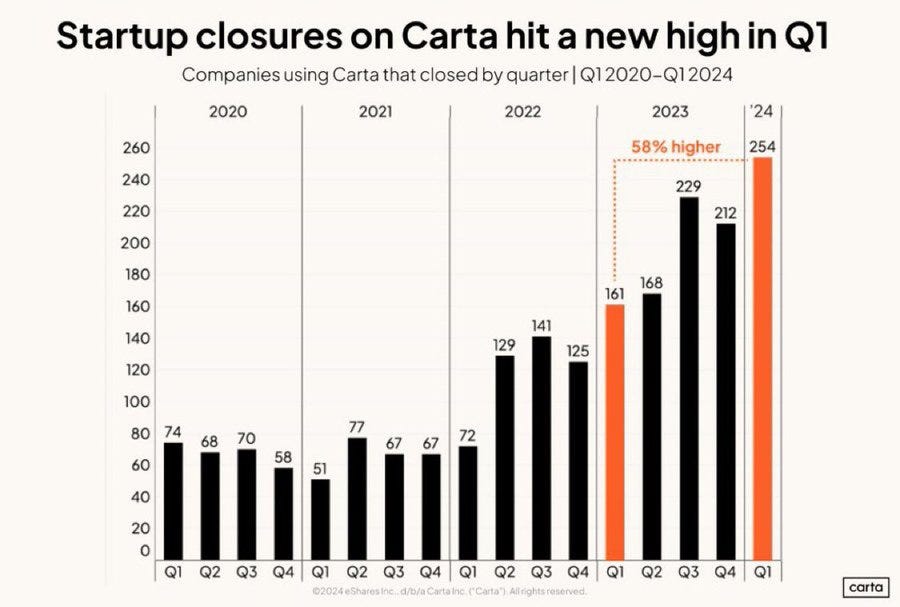

We’ll introduce some alternative data from Carta and Revelio, which suggests that this pain is already being felt in the Unicorn Economy, in the form of a ‘series A crunch’ and early evidence of employment weakness in tech. These are early indications at both micro and macro levels that the fundamental engine by which this Unicorn Economy operates is running dangerously low on fuel, in the form of liquidity

For many in my world, Powell's pivot to easing could not come at a better moment.

The Unicorn Economy runs on ZIRP

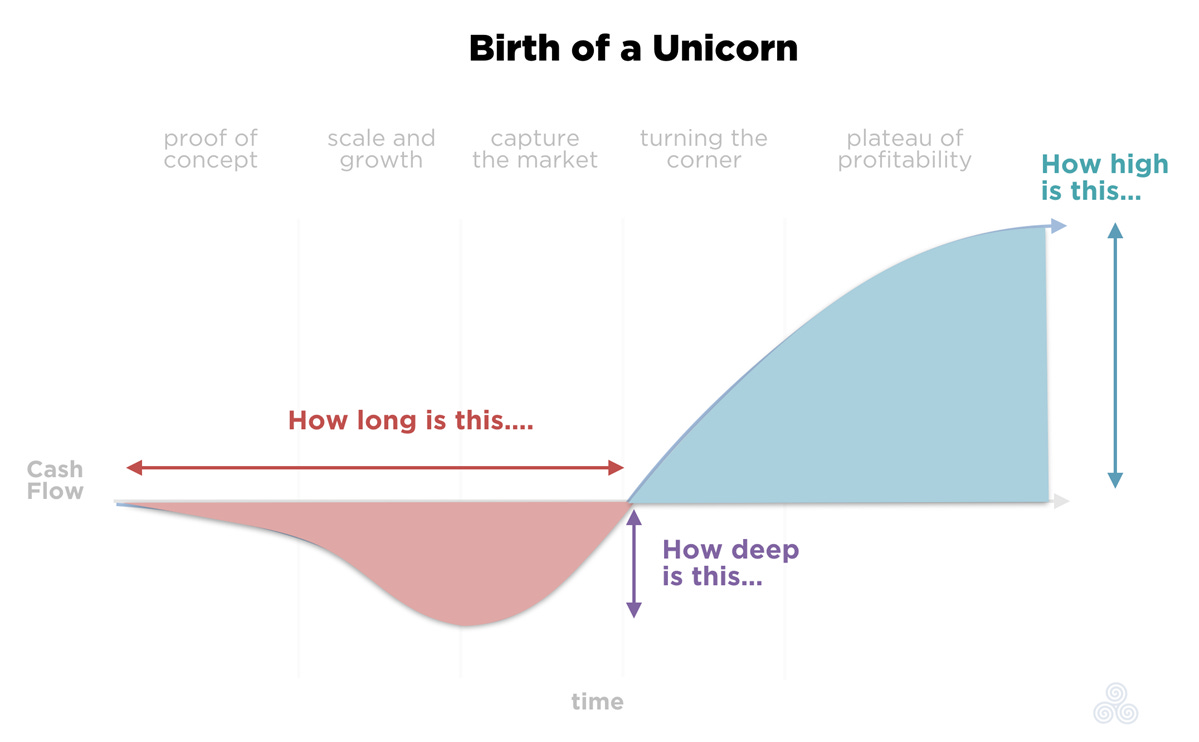

The core idea in the original piece from 2016 was about tech stocks, particularly startups or other firms that burn money today for a big pot of gold tomorrow. These companies (with high P/E stocks being a classic example) had more exposure to interest rates ("duration") than many people in tech appreciated.

The relevant principle here being 'there are bonds in the stocks,' which applies doubly to stocks where the bulk of the present value is a function of positive cashflows way down the line. The good examples then being SpaceX, Tesla, and Uber.

In short, when you zoom out, the time-value payoff profile of a ‘unicorn’ actually starts to look a lot more like the payoff profile of a very long ‘duration’ bond, even before you get to the point where you throw them in a portfolio (as almost all investors inevitably do). The core insight being, hey, if you think about it, startups are kind of like stocks with really high P/Es, both of which are valued based on payoffs way down the line. Meaning that in a very real sense, they have a lot of long term interest rate sensitivity or what we call in the biz: ‘duration.’

Meaning when you bought a stock at 100 P/E (or infinite insofar as they have no positive earnings), you are making a bet that you will either have to wait a very long time to get those profits/dividends/buybacks. Or there will be a lot of change (aka volatility to the upside) along the way in a short order.

The second part of that bet is the asymmetric upside that we look for when we invest in stocks. The former aspect actually turns the high-flying tech stock into what amounts to a very long-term bond.

Meaning the price of that bond, like any other financial asset, was impacted by the change in the risk-free rate. That risk-free rate, recall, after almost a decade of ZIRP, was basically zero. Pushing investors ‘out the risk curve’ (as an old mentor used to say) as rates/spreads/yields on the shorter duration, less risky assets compressed the returns to the point where it made sense to add risk.

In this light, the huge boom in the unicorn economy after the financial crisis makes a lot of sense. The goal of the historically easy monetary policy was to drive capital away from relatively safe and stable investments like cash and short-term paper into longer-term, more stimulative things. It just so happened that this investment also mirrored the preferred payoff structure of investors looking to 'extend duration.

Moving Out the Risk Curve

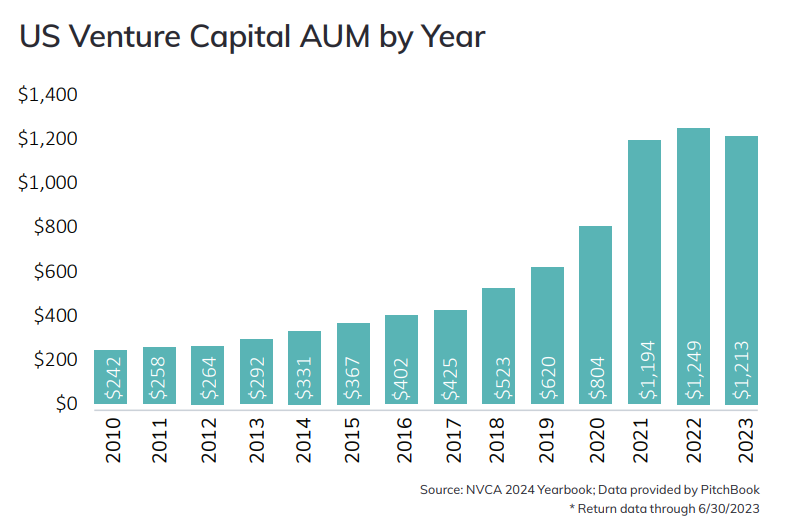

As a reminder, the biggest pools of capital in the world are sovereign wealth funds, endowments, and public pensions. These are managed by people who think not just about tomorrow or the day after, but about decades into the future. Many of these “allocators” (as they are called, not to confuse them with “investors” or “managers”, who do the dirty work of buying and selling actual securities) are tied to benchmarks that are explicitly linked to long-term rates and/or return targets. Meaning this move the ‘out the risk’ curve for many of them was mechanical, and had as much to do with their asset-liability management as any particular conviction about this or that private vehicle. Again, as designed!

Push to Privates

The unintended consequences started with a surge in liquidity. Commensurate with this came a meme originating from one of the most successful endowment managers of all time: Dave Swensen at Yale (RIP). Swensen made the essentially reasonable argument that an endowment should have investment horizons decades-long not years-long. This put Yale and other endowments in the unique position to take positions in assets that provided risk premiums to compensate investors for a lack of liquidity, transparency, and timeliness.

In short, if you are investing for hundreds of years, you should find managers with long horizons who take advantage of those long horizons to buy assets out of favor due to these negatives.

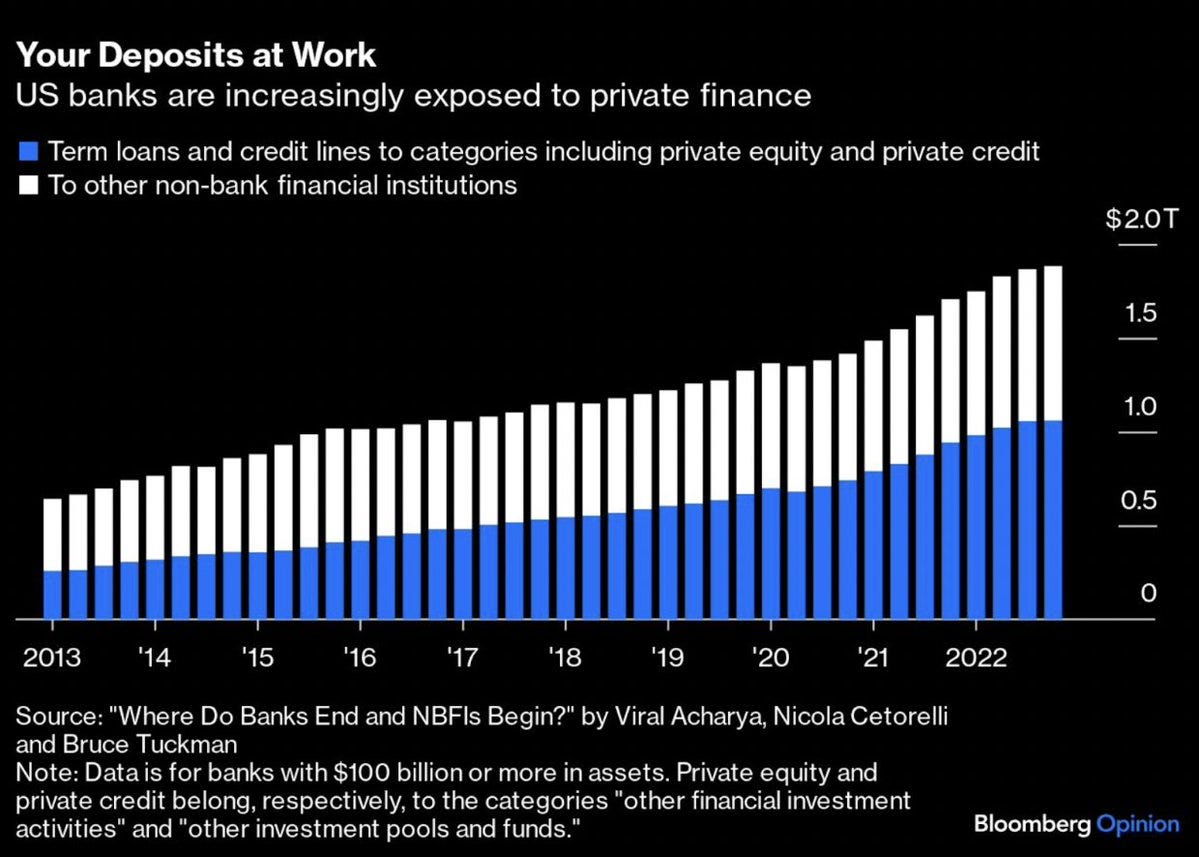

Perhaps most popular of all were private funds, where private equity and credit have a plausible argument that they represent differentiated value to long-term investors owing to the various advantages of the asset class, many of which mirror the goals of an endowment: tax, leverage, and occasionally operational or investment alpha.

Fundamentally there’s nothing wrong with private equity! In fact, you would expect a basket of public stocks to outperform the market were they able to add the leverage that a PE fund gets and then use that debt service to return capital to investors in a tax-advantaged way (you pay taxes on dividends but not interest).

What happened though when these two things hit the market at the same time, was a bit more dramatic than anyone anticipated. Between the shift away from privates and then a secondary shift out of active management and into passive management for public market exposure, we basically killed the “startup hedge fund” as a viable business. Which, along with the Volcker rule, is why you hear so much about “Pods” these days or multi-strat funds. The economies of scale are too big!

Anyway, when I wrote about the coming normalization of monetary policy in 2018, I was counting on a 2-3 year timeline until the eventual tightening started to bite. In late 2019, it looked like this tightening was beginning to take effect. What we got in 2020 was a bit of a surprise. Covid meant a return to both accommodative monetary and extraordinarily stimulative fiscal policy, along a weird cultural experience (lock-down) which in many ways felt like it ‘accelerated the future behavioral changes’ many tech startups were essentially betting on.

Think about the covid darlings: Zoom, bike startups, uber eats, Robinhood, crypto, Airbnb.

So rather than the punch bowl getting taken away, what we got was a massive wave of money printing and techno-optimism, resulting in a veritable food fight in early stage venture.

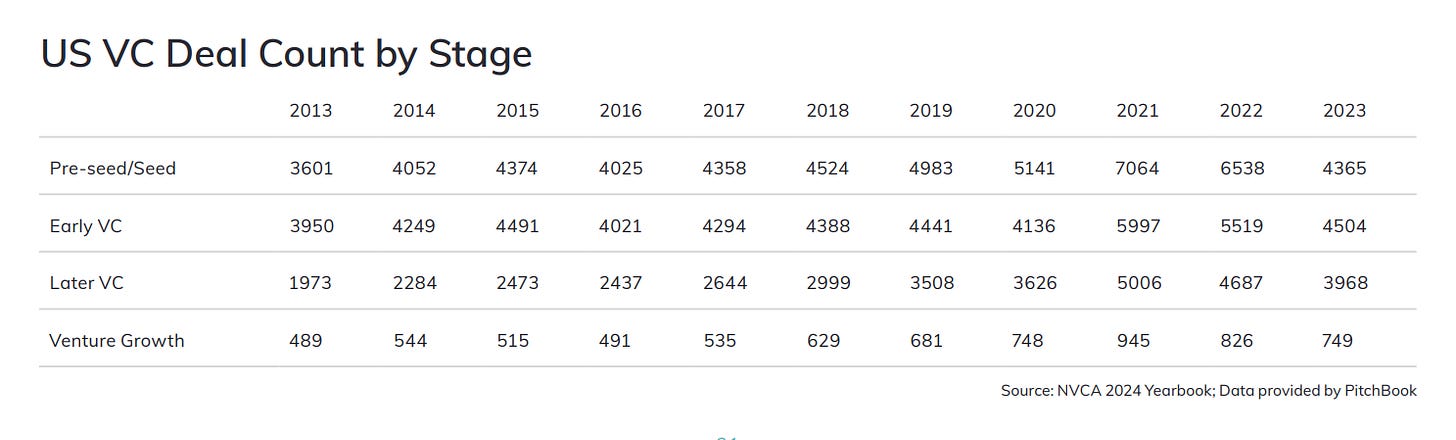

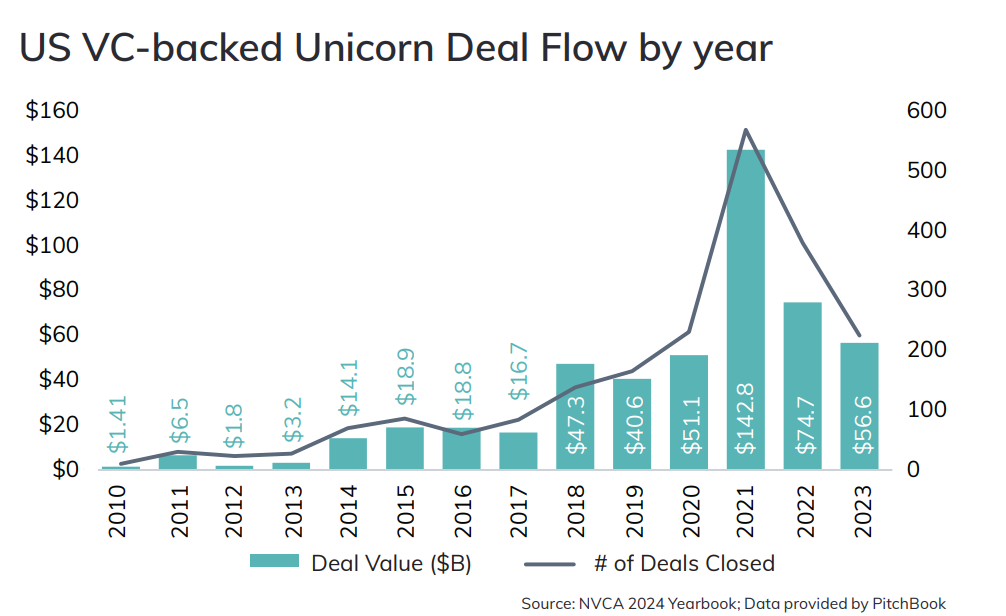

2021 saw a 40% surge in the number of ‘seed’ deals.

Shortly thereafter, Powell was forced to engage in record tightening, raising rates by 500 basis points and sending both bonds and stocks into a ‘dirtnap.’

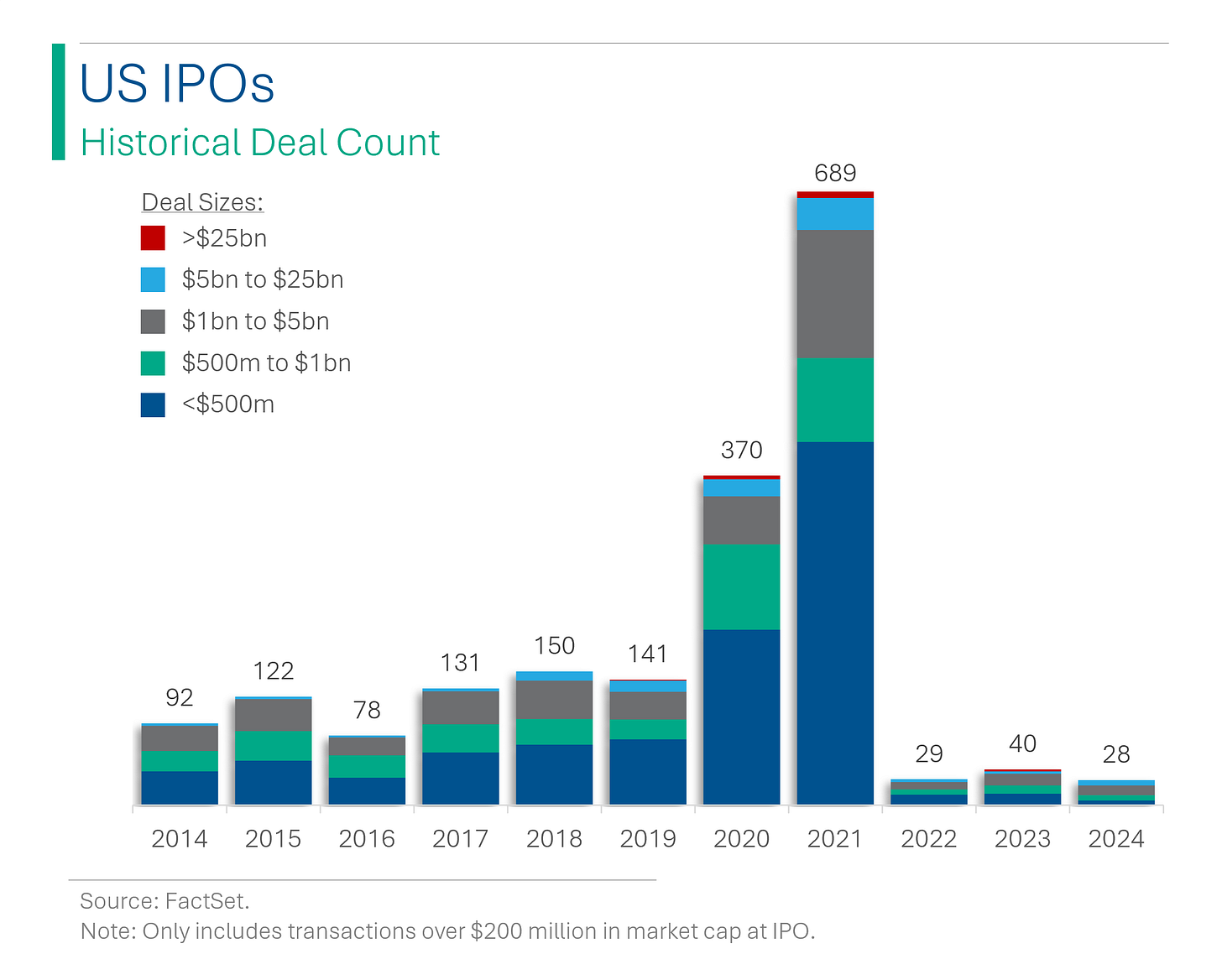

Which, when combined with an anemic IPO market…

and the widespread slowing of M&A activity…

resulting from many high-profile antitrust cases…

meant the Unicorn Economy hasn’t seen this few good exits since 2016!

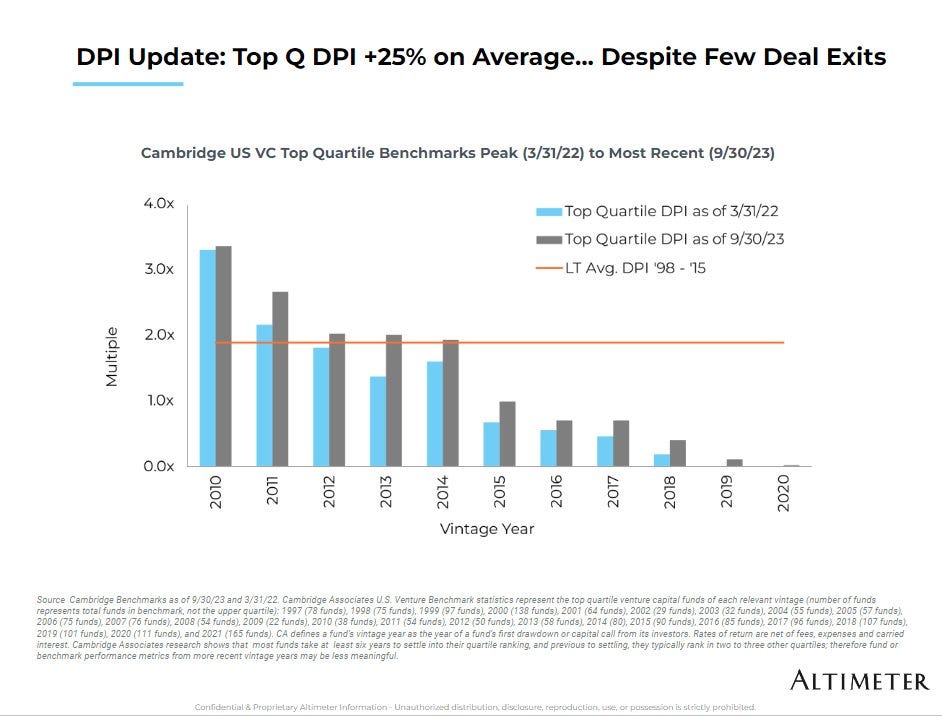

Leaving many a VC without having returned much liquidity to investors. Which is measured by something called DPI (or the ratio of “Distributed to Paid In” capital). You can see below the recent vintages are trailing well below their 2017-2020 peers.

This means investors not only haven't returned capital to their investors, but those LPs (limited partners the ones investing in the venture firms) also haven't rolled those funds back into second, third, or fourth funds!

When you combine this with the lag in startups that got started in 2020-2022, there’s a record amount of startups coming to market right at the time when the venture firms that would normally fund them are feeling the pinch from the part of their portfolio most impacted by the pain in public markets.

Leading to a “Series A Crunch.”

These venture firms are made up of very real humans, and when they have to tell their LPs that “nope, sorry, we’re still waiting on Stripe’s IPO + 6 months to realize our 20x mark - which btw is also 4x of the fund and hence represents 90% of your total return,” the last thing they want to turn around and say is “well we put another $5m to work in a pre-product-market fit company with $100k of revenue and $5m of liquidation preference.”

No way.

Which, ironically, is also why they can get away with $20m in a ‘from scratch’ foundation model AI company. Because at this point, they can point to the realized value from the OpenAI, Anthropic, Mistral’s of the world and go, hey there’s a path to exponential use here. Which historically has been a very good indicator of forward capacity to monetize.

Reminding us of one of the best moments from Silicon Valley (the show):

Which brings us full circle. If you are looking for causal reasons why so many startups are having a hard time hitting series A,B it’s a function of excessive liquidity early in the cycle, followed by record monetary tightening. What we are seeing is how those dynamics play out via the incentive structures and lifecycles of the venture shops that fund them.

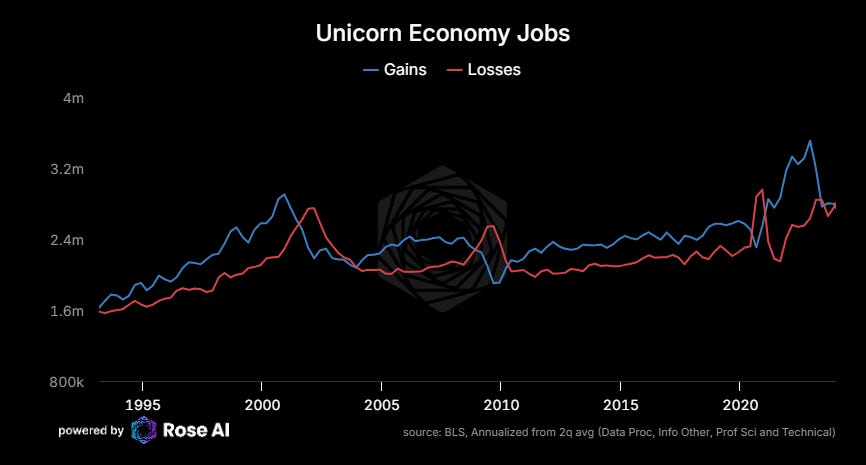

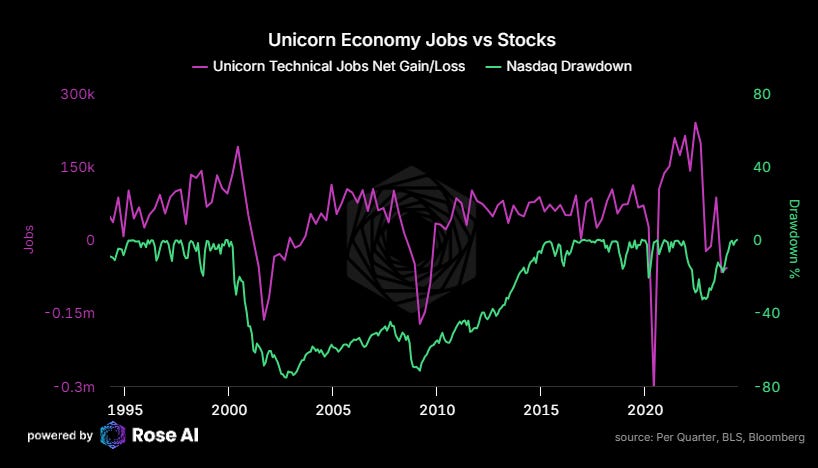

Meaning, while many major tech companies were able to crawl their way out of the pit of worry via cutting costs and expanding multiples, the labor market for tech workers continues to see layoffs. By looking at data from one of our vendors, Revelio Labs, we can see bottoms-up indications that tech layoffs are high.

This data is triangulated BLS data, which shows net job losses in the sector.

Job gains - losses has historically acted as a good proxy for pain in the Unicorn Economy.

So there you have it. While headline growth and labor conditions in the US economy remain strong, there appear to be growing signs of pain in the early-stage startup world, or what I call the "Unicorn Economy.” In this piece, I’ve tried to lay out the context, history, and logic for this call as well as provide some early data-driven evidence that the pain is real and binding.

Last week Powell confirmed that the bias of the Fed was now to easing, and indicated that we might see our first cut in a long time this September. For those of us in the Unicorn Economy with a lot of exposure to duration (i.e., everyone), it couldn’t come a moment too soon.

Disclaimers

Charts and graphs included in these materials are intended for educational purposes only and should not function as the sole basis for any investment decision.

THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT ROSE TECHNOLOGY INVESTMENT OBJECTIVES WILL BE ACHIEVED OR THE INVESTMENT STRATEGIES WILL BE SUCCESSFUL. PAST RESULTS ARE NOT NECESSARILY INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. AN INVESTMENT IN A FUND MANAGED BY ROSE INVOLVES A HIGH DEGREE OF RISK, INCLUDING THE RISK THAT THE ENTIRE AMOUNT INVESTED IS LOST. INTERESTED PROSPECTS MUST REFER TO A FUND’S CONFIDENTIAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM FOR A DISCUSSION OF ‘CERTAIN RISK FACTORS’ AND OTHER IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Bonus chartbook

![[endowmentttt.jpg] [endowmentttt.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ltT7!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1ea69b04-71e9-4f57-a4b7-10b0e7762708_483x293.jpeg)

Totally agree, and directly feeling a lot of these dynamics. I wonder if Powell’s easing, which isn’t going to be that significant given fundamental conditions, will make that much of a difference. Better than nothing, I suppose!

Silicon Valley- long on vision, short on maths. The problem started when everyone thought they could be David Swenson and get the same result. The risk premium just got competed away.