The Return of the 23-Year-Old Trader

Why I'm Posting My Track

Today we’re going to do something I haven’t done in a very long time. We’re going to flash the P&L.

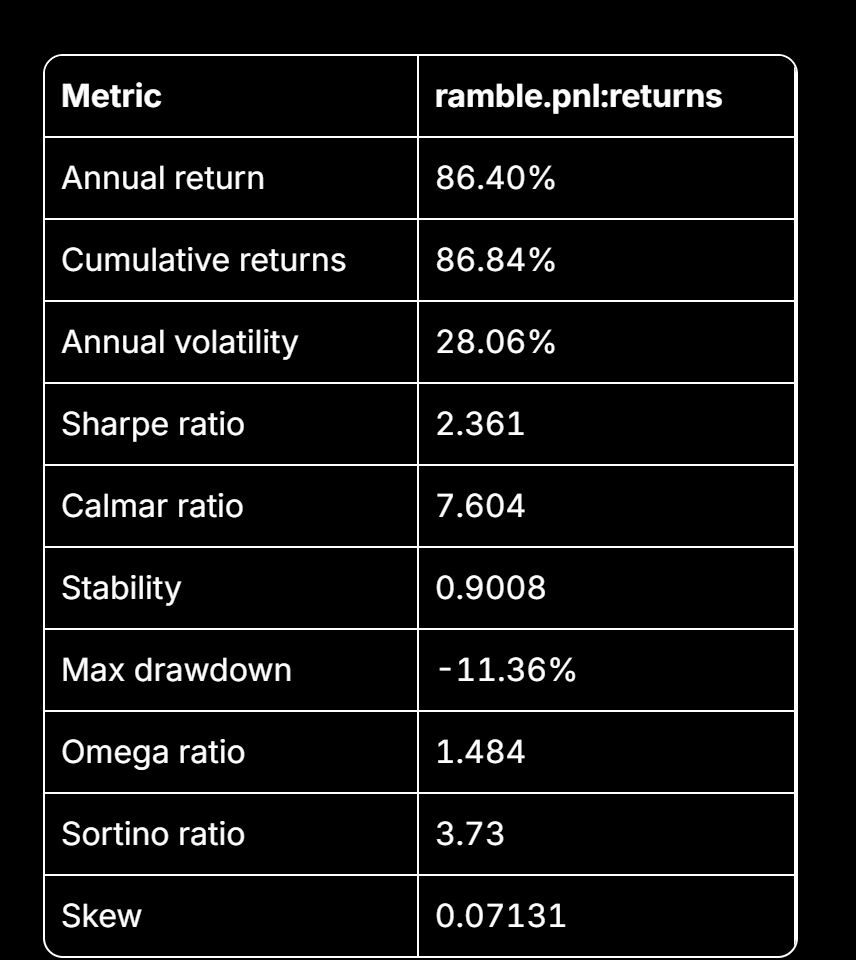

86% returns in the past 12 months. 2.36 Sharpe. -11% max drawdown.

Now, I can already hear the more cynical of you saying, “Campbell, this is the first time in years you’ve done this. Clearly it’s because you’re doing well.”

And normally, usually, I would agree.

Somewhere along the way at Stanford or Bridgewater, I learned a lesson that I probably need to unlearn. The notion of false humility.

The Stanford GSB Lesson

See, when I got to the Stanford Graduate School of Business (aka “GSB”), I had a difficult time making friends. I was living off campus with my partner (of five years), and I missed the pre-onboarding trip to Columbia (thanks JJ) . Add in the fact that a) I don’t drink, b) I’m a fair bit aspy, and c) I wasn’t ready for the culture, it took a good six months to really find my legs, find my people, and start being “me.”

Somewhere around month six, I was complaining to (my now dear friend) Saad about the fact that I didn’t understand why, frankly, I wasn’t more popular. I forget exactly the context, but the gist was me barking about how I didn’t get why everyone loved so and so, and why wasn’t I being invited to whatever party or dinner.

And Saad, to his great credit, looks me right in the eye and says: “Well Campbell, the reason everyone likes so and so is because they’re fun, they’re positive, they make sure everyone around them is having a good time. You just spend all your time being smart and negative.”

Gut punch. But the man had a point. One of those moment in time pieces of feedback.

I’d spent my whole life winning rooms. Played competitive football and lacrosse. Oxford. Competitive debating. Ninth in the world at debating. Topped my class at Lehman, got onto the hardest desk, earned a portfolio, got into Stanford. Played competitive football and lacrosse.

Each of these environments was zero-sum. Winning was the priority. I could focus on being the best, at the exclusion of having people like me.

But Stanford wasn’t that game. In fact, the biggest lesson, to me, was that there were so many other ways of being successful, and that my obsession with winning was actually getting in the way. I had to learn a different way of being.

So I changed. I masked the pure aggressive tendencies. Learned to be positive, collaborative, team-oriented. Hide. This served me reasonably well at Bridgewater - competitive but social and dynamic. When I became a leader afterward, I wore all those messages.

But here’s what I’m learning I need to unlearn: what I thought was representing a healthy relationship with my ego reads to others as lack of confidence or lack of killer instinct.

Which is definitely not the case. It’s just sublimated.

I’ve done a lot of reflection recently. In particular with my relation to markets, entrepreneurship and ‘be the best version of yourself.’

Thing is, the more I reflect, the more I actually think that 23-year-old trader - the one managing risk, writing analysis, trusting his process in the middle of a financial crisis- that was closest to who I actually am at my base. The core. While a lot of people had to go and grow and find themselves, I was lucky enough to have the kind of crazy, stressful job that pulled the person I was out, at a very young age. Then circumstances intervened and I took another path. Until now.

To some extent, I’ve been working my way back there ever since.

A guy in a room, managing a portfolio, writing a blog.

The Synthesis

Bridgewater taught me to apply process systematically and rigorously. When markets are your only obligation, you don’t really need systems - you can just live in the data. But as life gets complicated - people, responsibilities, other projects - I let that discipline lapse.

Over the past year, I got back to it.

The results:

86.40% annual return

2.36 Sharpe ratio

28.06% annualized volatility

-11.36% max drawdown

7.60 Calmar ratio

3.73 Sortino ratio

For context: a 2.36 Sharpe for a discretionary macro book is exceptional. Most hedge funds would kill for 1.5+. The Calmar ratio of 7.6 (return/max drawdown) shows this wasn’t just gambling.

And I’m at an inflection point: I can either bank the win and coast, or I can use this moment to pause, reflect, and build something.

So, I’m choosing to synthesize my two worlds:

The 23-year-old trader who sees macro trends and has conviction

The institution builder who understands systems, data, and AI

If there’s a life’s purpose here, it’s this synthesis. And the time is now.

The Meta-Project

I’m not just going to be posting portfolio updates. I’m building in public.

The Portfolio (this post) - Current positions, performance, thesis

The Systems (future posts) - How we’re building infrastructure to scale the process

The Meta-System (the real work) - Going back to my graduate research on game theory, cognitive dissonance and machine learning.

Here’s the core problem every quant system faces:

Scenario A: You’re fundamentally right, market moves against you

→ Rational response: Lever up, lean in

Scenario B: You’re getting negative feedback from reality

→ Rational response: Get less confident, reduce exposure

Both are conceptually true. But how do you know which scenario you’re in? This is where cognitive dissonance becomes the engine of learning.

Modern LLMs are brilliant at learning from static corpuses. They can even learn in context (kinda like working memory or RAM). But they cannot compound learning over time. They have no memory of being wrong. No ability to update their confidence based on outcomes. No meta-structure for distinguishing between “the market is temporarily wrong” versus “my model is wrong.”

This is the black box problem. The overconfidence problem. It’s also why quant funds blow up spectacularly.

Bridgewater’s solution: Linkage Testing

They didn’t just model “if X happens, Y happens.” They modeled chains of linkages:

X leads to Y

Y leads to Z

Therefore X should lead to Z

When X doesn’t lead to Z, you have diagnostic information:

Is the X→Y linkage broken?

Is the Y→Z linkage broken?

Is there an omitted variable A that’s actually driving Z?

This gives you degrees of freedom to iterate. It’s not just “the model failed” - it’s “this specific mechanism broke down, here’s where.”

What we’re building here:

In the next couple of posts/months, we’re going to lay out a meta-learning system that uses markets as the training ground. Markets provide:

Immediate feedback (you’re right or wrong, no ambiguity)

Causal chains (policy → rates → credit spreads → equity vol)

Cognitive dissonance (when linkages break)

Monetary stakes (aka accountability and truth constraints)

Future articles will lay out:

The principles we’re compounding on

The framework for teaching machines to think (not just predict)

How to apply this in the context of markets

We’re doing it live. In public. With real capital.

How Conviction Compounds

So how do you get to 86% returns without being reckless?

It’s less about taking insane risk and more about conviction compounding through Bayesian updating.

Look at the correlation chart. The portfolio has maintained high correlation to precious metals throughout the year (tilting more towards silver recently) while staying relatively uncorrelated to US stocks and bonds. This isn’t luck. It’s thesis-driven positioning.

The Process:

Step 1: Form Base Case Hypothesis

China Gold Thesis (2015):

China faces property collapse → two paths:

Path A: Take the pain (Japan route - write downs, recapitalization)

Path B: Print and debase (accumulate gold, depreciate RMB)

Initial view: 50/50, maybe even favoring Path A.

Step 2: Reality Provides Evidence

Over the next decade:

They had every opportunity to take the pain

They chose to extend and pretend

Private gold imports exploded

PBOC accumulation confirmed

RMB depreciation began

Step 3: Update Confidence

Each data point that confirms Path B raises conviction. This isn’t stubbornness - it’s learning.

An old mentor (hi Andy!) recently accused me of being “absolutist” in my thinking about China’s demand for gold. My response: Actually, no. When I first gave this thesis to the world, I thought it was equally likely - if not more likely - that they would take the Japanese route. Take the pain, write down the assets, recap the banks. You know, the playbook for debt crises.

My conviction on their demand (both public and private) for gold has only gone up in response to a decade of them refusing to do that when they had all the opportunities in the world to do it. Because the only reason they wouldn’t, is that they are going for the whole kit and kaboodle. Taiwan. Dominance of the Pacific. The Dollar…I didn’t start thinking that, I started thinking it was an interesting trade. What gave me conviction was holding that view, and constantly updating both my model of the world, and forward expectations in response to events. WMPs. Shengjing. Evergrande. At each step, an opportunity to come clean. At each step, more printing.

This is what Druckenmiller describes:

One core macro view

Constantly evaluating

Size scales with conviction

Conviction scales with validation

You don’t start at 80% precious metals. You arrive there after years of:

Thesis → Prediction → Observation → Update → Repeat

The Solar/Silver Extension

By this token, my silver position comes from the same process:

Base thesis: AI needs energy (as a kicker to the same “Gold in China” dynamics above)

Extension: Solar is the scalable solution

Implication: Silver demand will surge

Time horizon: 3-10 years

Market behavior: Brownian motion around this attractor state

The “attractor state” is the market continuously revising expectations upward for:

Energy demand (AI training + inference)

Solar’s share of new capacity

Silver intensity per watt

The Key Insight: Dissonance as Signal

You size aggressively not when price validates you, but when:

Your thesis is validating (China keeps printing, AI keeps outperforming and with it, your future expectations of energy demand)

Asset prices are lagging (silver still sub-$35, gold/silver ratio still 80:1)

That gap - between fundamental reality and price - is where conviction lives.

This is the dissonance. Not between your worldview and price. But between:

Observable validation of your thesis AND

Market prices that don’t reflect that reality YET

The Actual Portfolio

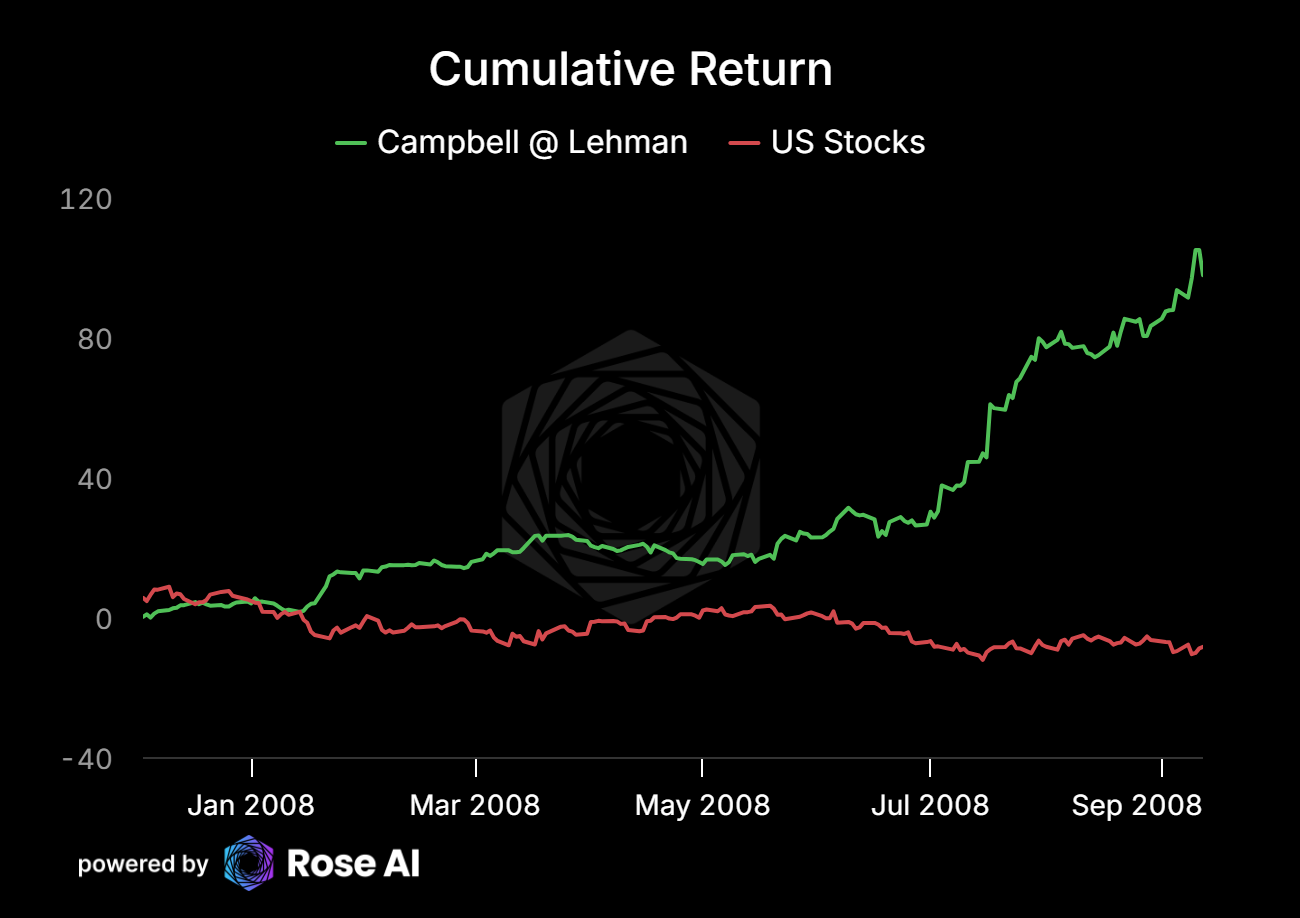

Looking at the performance chart, you can see the steady compounding through most of the year, with acceleration in recent months as the precious metals thesis plays out.

Here’s the current positioning:

Core Thesis Positions:

Heavy precious metals (gold + silver + miners)

Long AI/tech infrastructure

Short credit spreads

Long/short trends in tech/finance/retial

Short equities via vol/options

The correlation charts tell the story: This portfolio moved with precious metals, not with traditional 60/40. When stocks and bonds both struggled mid-year, the portfolio kept grinding higher.

A Note on Execution

We’ve started rotating some positions into options - buying convexity as theses play out. But I’m including this not as a victory lap, but as a lesson in a) the need for systems, b) the value of execution, and c) a reminder about the perils of ego.

Recently I’ve been working at a client that limits my ability to access the internet during trading hours. I knew I should be shifting into options but every time I tried, the market was closed, or the trade’s didn’t clear, or my broker would *surprise* demand some other hoop to jump through to execute (what we call “the princess is another castle). Meaning even though I was 100%+ long silver and gold, as I watched the price action, as I was making money, I was furious.

Not because I was losing money - I wasn’t, I was printing. But because if I’d rotated into options when I wanted to, I’d be up even more.

And that’s when I knew: Being angry about “not making enough” while you’re making a lot is the classic greed signal. Time to take profits.

So I started selling. Took 20% off my silver and gold positions yesterday. More to follow.

But here’s the deeper problem: I wouldn’t be in this position if I had a system to execute properly in the first place. The options rotation was the right move - I just couldn’t execute it in real-time.

This is the activation-execution loop problem. You don’t have this issue when you’re 23 and staring at screens for 10 hours a day. You do when you have a life, real clients, and trade a couple hours a month.

This is why I need to build the machine. Not to replace judgment, but to execute when I can’t. To systematize myself the way Ray systematized himself decades ago - not by imitating his system, but by building mine.

This is what we’re building toward. Synthesis.

Where This Started

I know what you’re thinking. This is the first time in years I’ve posted performance. Of course it’s because I’m winning.

Fair enough. But let me show you something else. This isn’t the first time.

This was me at 23:

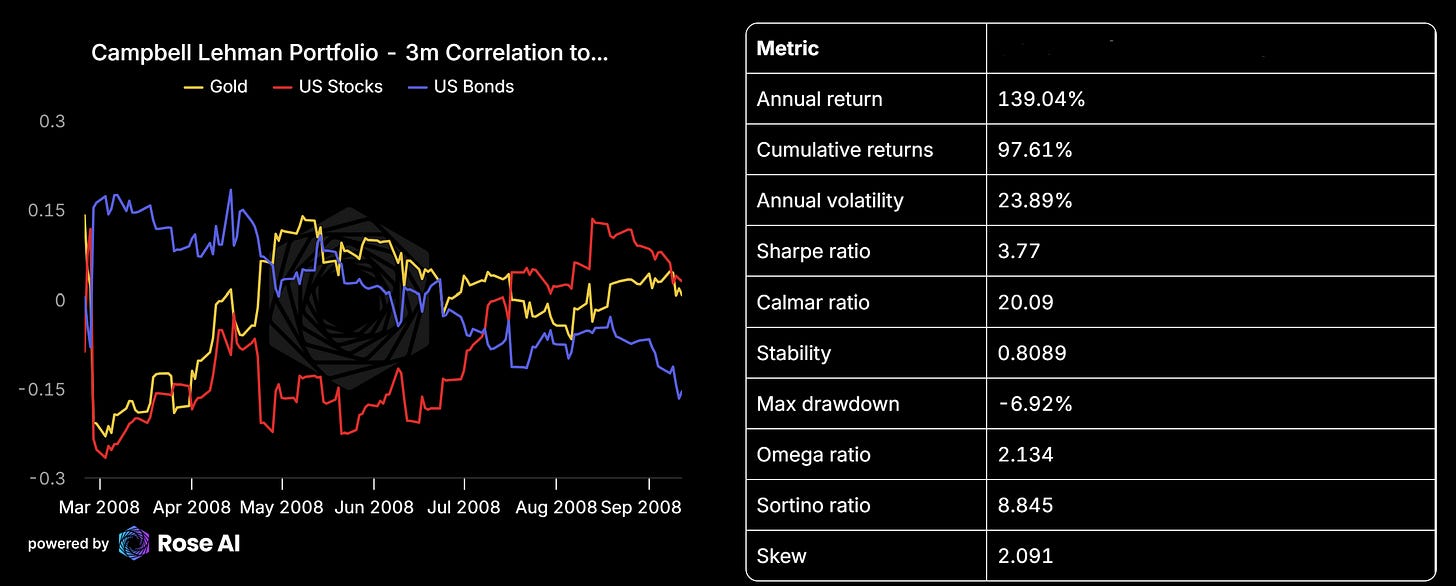

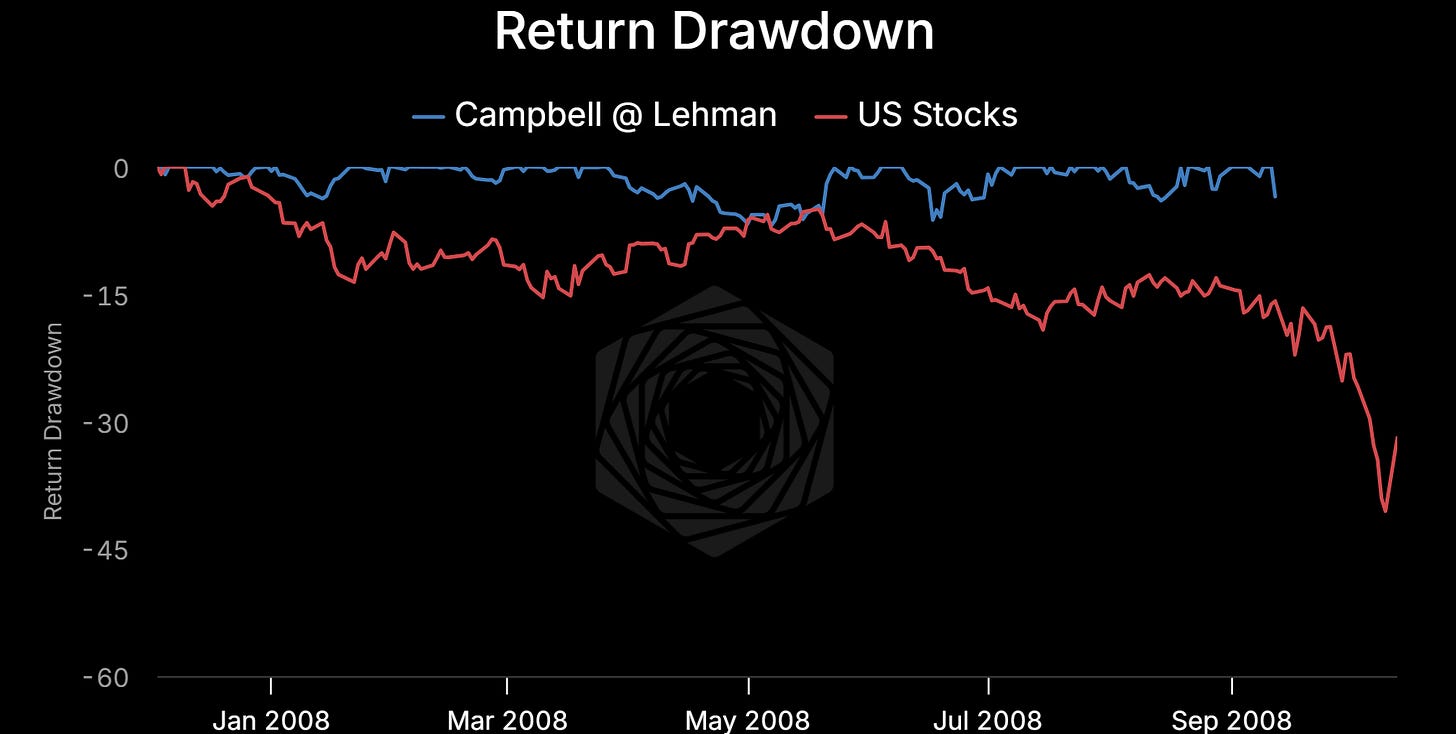

139% annualized return (Jan-Sep 2008)

3.77 Sharpe ratio

20.09 Calmar ratio

-6.92% max drawdown

23.89% volatility

During the GFC. While the market collapsed. On a $10M book at Lehman. Dumb kid of out grad schoo.

Not just good returns. A 3.77 Sharpe during the most volatile period in modern market history. Better risk-adjusted returns than my current book. Lower drawdown. (The power of the ISDA!) Positioned for chaos while everyone else was dying.

I was the kid who was long commodities in the first half of 2008 and then short financials in the back half. Who made 139% while the world burned. Who managed risk better than funds with decades of experience (if I do say so, lacking humility).

And then, nine months into my first real job, the clock stopped, I was unemployed and it was time to apply to business school.

But look at those numbers. -6.92% max drawdown. That’s professional grade.

That’s who I actually am. The human in the machine.

Coming Home

For the last decade, I’ve been trying to help other people systematize their investment process with Rose. Building tools, frameworks, infrastructure. But they don’t really want my help - they see me too much as a trader, not enough as a tech guy.

So I’m done solving other people’s problems. I’m coming home.

I’m taking what I’m actually good at - trading - and using a decade of AI/data experience to systematize myself.

The Lehman track record shows I could trade. The current track record shows I still can. But that’s not the goal.

The goal: Can we build a machine that actually learns? That compounds conviction over time? That knows when to lever up versus when to cut?

Not curve-fitting. Not a black box that explodes. A system that thinks, updates beliefs based on evidence, and calibrates its own confidence.

Markets are just the laboratory. The place where you get immediate, monetary feedback on whether your cognitive framework works.

This is about synthesis: the 23-year-old trader’s intuition + the institutional builder’s systems + the AI researcher’s frameworks.

What’s Next

This is the first of three posts:

Post 1 (this one): The goal

Post 2: The process

Post 3: The machine

We’ll also provide more granular updates going forward. Monthly portfolio snapshots. Weekly if things get interesting. The full trade log at year-end.

Not because I need to prove anything. But because this is the project.

Building a machine that can actually learn to trade markets. Using my own portfolio as the training ground. Doing it in public. With real capital.

The 23-year-old trader had the intuition. The institutional builder has the process. The AI researcher has the frameworks.

It’s time to bring them all home.

Disclaimers

I've been liking your posts and appreciate learning more about you even than when we worked together. E.g. about your family and also this section:

> See, when I got to the Stanford Graduate School of Business (aka “GSB”), I had a difficult time making friends. I was living off campus with my partner (of five years), and I missed the pre-onboarding trip to Columbia (thanks JJ) . Add in the fact that a) I don’t drink, b) I’m a fair bit aspy, and c) I wasn’t ready for the culture, it took a good six months to really find my legs, find my people, and start being “me.”

I definitely relate to that.

interested