How to Short a Startup

The invention of the "Snow Put"

This one is going to be short on prose, long on diagrams.

Long story short, after I left Bridgewater, and before Rose got off the ground, there was a hedge fund called Snow.

The goal of Snow was pretty simple. We wanted to make a hedge fund that actually, you know, hedged something.

In particular, I was interested in the idea of hedging your life. Taking out the systemic risk (aka ‘beta’) which, according to my portfolio math, meant that everyone would then be freed up to take MORE risk in the areas that they really had alpha.

Aka diversify your life.

My experience trading through the financial crisis at Lehman Brothers taught me that sometimes, the world just moves, and with it, a lot of babies get thrown out with the bathwater. For me the baby was a promising career as an up and coming proprietary equity derivatives trader, but there were examples all around of folks with less who got hurt more.

The specific idea to help startup people hedge their startup equity was kind of an outgrowth of a Nobel prize winning economist by the name of Shiller, who argued that homeowners should be able to hedge their home value. His idea was to help retail take out a short position in a hyper-local futures contract tied to the value of their local residential real estate market.

This was four years after graduating from business school at Stanford, and I saw a lot of my classmates extremely levered not only to their particular company’s equity, but to the market for startup equity in general. A lot of folks who needed to hedge their life.

Keep in mind this is 2015. We were coming up on a decade of ZIRP (aka very low interest rates and QE) and the startup space was seeing a flood of capital, “moving out the risk curve” and chasing extra return in illiquid, long duration VC. Further, funds like Tiger Global had breached the Rubicon between public and private markets and made a killing investing in “unicorns” (210 at last count), leading to a host of ‘fast followers’ bidding up the price of growth-stage startup equity.

A phenomena I coined the “Unicorn Economy”

To compound things, there was this idea for a company called Rose jangling around in my head, the tool I always wanted to use a data driven investor.

The “thing” that would connect to all your data sources, and then use AI to help find, analyze, store and visualize your data. Somewhere in it we would also build a marketplace, where the same folks buying the data could turn around and sell their cleaned up, derived data sets back into a public marketplace. Where you could buy and sell alpha, basically.

The full story of Rose deserves another ramble, but basically the very good friend from Oxford I left Bridgewater (and Thrive) to build Rose with got cold feet, leaving me on the altar, the day before he was due to fly to SF and apply to YC with me. His wife nixxed it at the last moment, and in an instant I saw the timeline for building this smart database or whatever the heck we would make go from 3 to 10 years. He was that good (which we know in retrospect cause last year he got recruited by Anthropic, of all places, where he’s helping them build AGI now for $$$).

Anyway, so here I am in 2015 thinking, oh boy, this thing is going to take like a decade now, and the good times aren’t going to last that long.

Why?

Well….

a) nothing good last forever (lol, there’s that childhood trauma)

b) eventually inflation would come back and with it, the removal of ‘accommodative monetary policy’ fueling the startup fire

c) the Chinese credit system would probably blow up by the time I was in a place to raise material money on this AI thing, and then I would be hosed

d) if China didn’t implode, it was because they chose conflict, which would lead to inflation (remember conflict is inflationary!) which would pull up yields, which would pull liquidity from VC etc.

Which got me thinking. What if there was a way to hedge the systematic risk inherent in investing in early stage tech equity?

So I went around and talked to my friends, did the YC thing of ‘if I built this, would you buy / need it?” The answers I got were interesting:

For employees, the idiosyncratic risk just absolutely swamped the systematic risk. Yes, a lot of growth stage employees were getting massively subordinated and, in the process, invertedly exposing themselves to a ton of market risk in their life portfolio even after they had ‘made it’, but the idiosyncratic risk of their particular startup was like 5x more important to the outcome than the market.

For investors in startups, the case was much stronger, but there were institutional/cultural reasons they couldn’t even been seen to hedge. Things that made no sense to me as a macro investor, but started to make a lot more sense as I got deeper into the market.

See as a (former) macro guy, my job was to time the market.

Timing markets is hard! It takes a ton of time, a lot of data, and most of the best VCs got there by picking the best teams/products/startups, rather than sitting their trying to time the waxes and wanes of the NASDAQ. Meaning not only is it potentially distracting and value destroying to have VCs punting the market, but culturally you kinda want your venture folks to be perma-bullish. Leave the shorting to the public markets guys. Again, to me this made no sense to me at the time, because really the best way to ignore the moves in public market is to hedge them out, but obviously now it makes a lot more sense.

Finally, there was the problem of liquidity. Any hedge would likely require investment, and while VCs may have some personal liquidity, many of them could not afford to pay the premium to hedge their biggest positions. The lack of diversification was almost as existential for the early investors (like my friends who had just made one or two successful early bets ) as the founders. I also learned that most founders were already so levered into their individual startup equity, that they couldn’t afford to hedge. There was no liquidity from which to buy the optionality to hedge their life!

Alas a gigantic market with no product!

The Snow Put

This was a real problem. You had two parties to a trade, both of whom kinda wanted to get out but couldn’t. Here I mean specifically the folks who invested in the early rounds of “unicorns” like WeWork, Uber and AirBnB that were already deep ‘in the money.’

So you have two sides who are both interested in a liquidity or downside protection, but the only asset they really had to bring to the party was the thing they were trying to hedge!

What to do?

Well this is where, ironically, my time at Lehman Brother’s came rushing back. After all I was a proprietary exotic derivatives trader in my other former life and what this situation really needed was some first class financial engineering. So I got to work looking at the actual structures underneath all these mega rounds and, for the first time, came into contact with the dreaded liquidation preference.

See, when Softbank or whoever puts in another billion into WeWork, they aren’t just buying equity. It’s not like going out and buying ten thousand shares of Google. What the VCs are actually buying is preferred equity, or as we called it on the desk in London, a convertible bond.

This is where you ask “Campbell WTF is a convertible bond and when will you tell me how to short startups?”

To which I answer, here comes the diagrams.

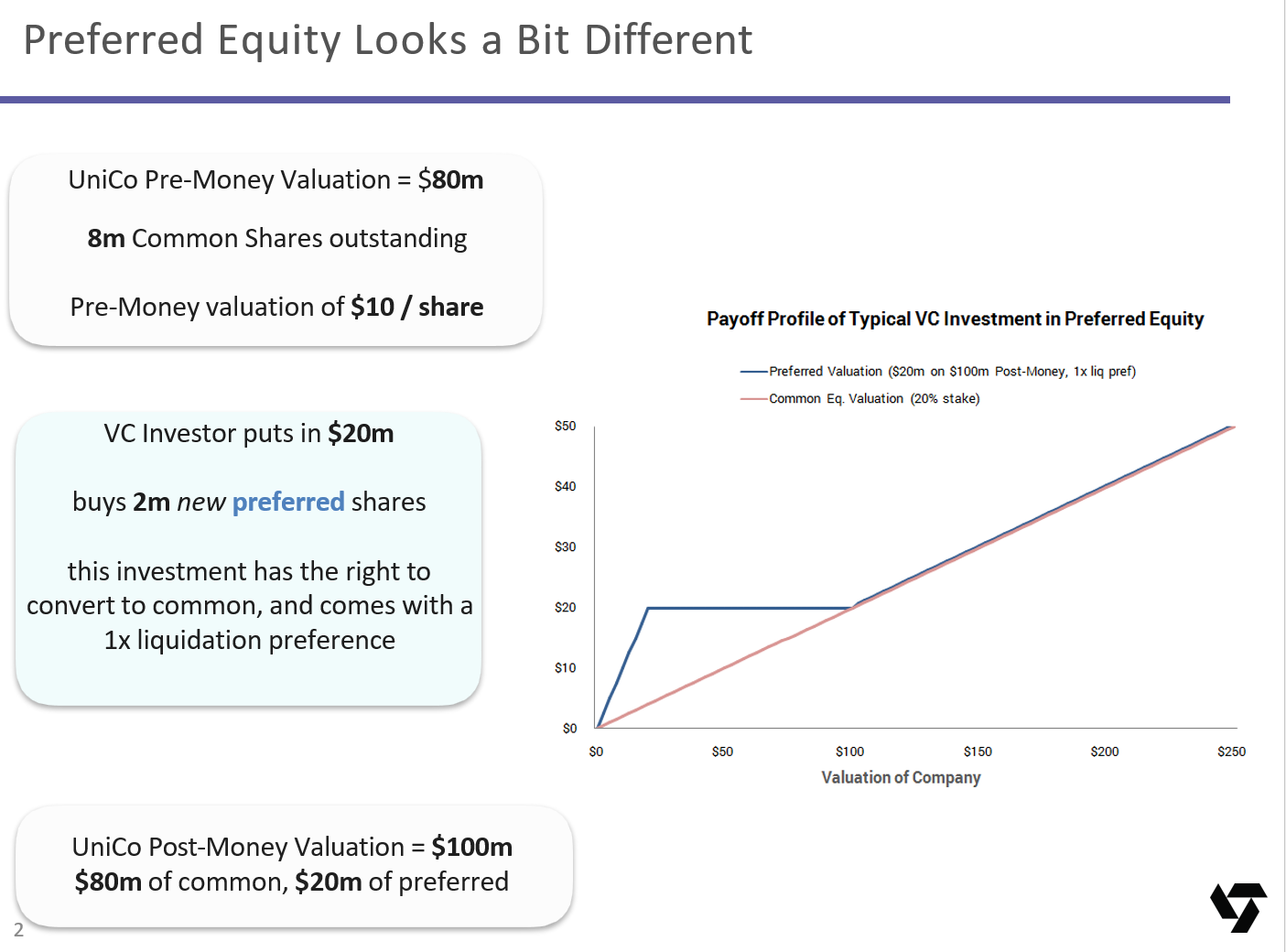

Let’s start with the payoff to an investor buying $20m of common equity in a company valued at $80m (pre-money).

The math here is pretty simple (though I’m sure I’m messing up some detail somewhere).

You buy 20% of the common shares, you get 20% or 2m out of the 10m total shares.

If the startup ends up selling for $200m, you get 20%, or $40m.

If the startup sells for $20bn, you get 20%, or $4bn.

20%. Always. Easy.

Now let’s add in the liquidation preference and make it a bit more realistic.

A “1x liquidation preference” is actually a pretty simple term. It says, “hey kid, if I give you $20m, at the very minimum, I want my money back if anything goes poorly”

Immediately you can see where the idea of this being a convertible bond came from, because it is!

This is where the ‘subordination’ of the early employees (and earlier investors) comes in. Because that option, the liquidation preference, the difference between the blue line (the preferred equity aka convertible bond) and the red line (the common equity) represents real value that has to come from somewhere.

Where does this value come from?

Well all the people that essentially get hosed if the company ends up selling (or IPO’ing) for less than the valuation this latest investor got!

It’s a little hard to see on the diagram below, but if you look closely you can see that the red line, the common (aka the employees), doesn’t even kick in until the “liq pref” (aka the venture capitalists) totally gets paid back.

“Meaning if WeWork, raises another billion at a $20bn valuation and the company sells for less than a billion, all the early employees get wiped out.”

Which is what I used to say.

Which is exactly what happened.

Anyway, so it goes.

So where is the magic? What’s the secret?

Well, the secret is that we don’t need to invent any new options to help startup investors hedge their equity, the venture guys (and gals) already invented it for us!

It’s the liquidation preference!

Those 2m preferred equity shares are actually two financial instruments, masquerading as one.

There’s the liquidation preference, which only makes money if the startup sells for less than the valuation at the time of investment (but more than the total amount of cumulative liquidation preference) and then 2m kinda, sorta SUPER-common shares. Common shares that are just clean claims on the value of the company, without subordination or protection.

How do you get at all this option-y goodness?

Simple as buy* the preferred equity from the venture capitalist (“San Francisco”) and sell the super common to a cross-over hedge fund (“NYC”).

(* or more realistically, enter into a pre-funded total return swap since there are terms against VCs selling pre-IPO)

What’s left is a a special kind of downside put option on the startup, which we dubbed a “Snow Put.”

You also can use those super common shares to fuel an actual market for early stage, pre-IPO tech equity. Keep in mind this is pre-blockchain mania and so this idea sounded radical.

Funny thing is even though these put options are imperfect (since you get NOTHING if the company goes all the way to $0), they are actually the perfect hedge for a particular group of investors: the very startup employees and early stage investors that sold the liquidation preference (aka Snow Put) to begin with.

Aha! The perfect hedge!

The math in reality gets a lot more complicated (because you have multiple rounds with multiple liq prefs), but nothing the folks who cracked the CDO-squared Mortgage Backed Security couldn’t make short work of.

You just need to be able to think through a lot of diagrams that look like this:

Which in real life looks like this:

The best part was that the market was so illiquid, the middlemen currently sitting between SF and NYC who were dealing primarily in ‘secondary’ (aka employee or early investor shares that is made saleable) made so much money currently, that there was an argument we should get these Snow Puts for free….

Since the cross-over investors in NYC should be willing to pay a premium for these super-common shares vs the subordinated common that they were currently dealing in.

That opened up a surplus. One we intended to sneak out the back with in the form of the Snow Puts. As our compensation for putting the deal together.

With the understanding that these liquidation preferences were likely best packaged themselves into a portfolio. When not able to be sold directly back to the employees.

Ironically it’s actually this instrument, the Snow Puts, which when packaged into a diversified portfolio that would enable VCs to actually hedge their systematic risk!

Isn’t it nice when things come full circle?

Anyway, enough for today. We’ll go into detail more later on this one if folks have interest. I legitimately think that more folks should be able to hedge their startup equity, and a couple of folks have brought it up recently, so we thought we would share the idea after almost ten years (!) to get the ball rolling.

All we ask is if you lift this idea: 1) You agree to call them “Snow Puts”, and 2) you let us know you are trying to do it, and allow us help with the math.

We don’t even really need to be paid at this point, I just want to help folks hedge.

I've been surprised that hedging risk in one's life hasn't become easier for everyday folks in recent decades.

Definitely in favor.