The Unicorn Economy - Part 1

January 22nd, 2016

Imagine for a moment all the people you know involved with startups.

There’s Sarah, the unflappable entrepreneur, disrupting the world, one line of code at a time.

There’s Malcolm, the savvy VC, listening to pitch after pitch for “Uber…for cats” and wondering when Woz and Jobs will walk through that door.

Entrepreneur, investor. OK, now open up the aperture a bit.

Think about the devs, the designers, the growth hackers and social marketing gurus that work with Sarah. The investors, lawyers, bankers, and accountants that work with Malcolm.

Think about Sarah’s customers, and the companies for whom Sarah is a customer. The co-working space she rents, the enterprises that host her site, her code, her payments, and her team’s conversations. Think about their founders, employees and investors.

Think about the firms that comprise Malcolm's portfolio, and the which count Malcolm's firm as part of their portfolio.

Each person, interconnected in a complex web of economic relationships.

I call this system the Unicorn Economy, and I believe it is headed for a bust.

Why?

All economies are subject to a natural boom-bust process in the capital cycle, and the Unicorn Economy is no different.

A bust is not due to any malice, greed, or particular ignorance of an individual or group, but rather a natural part of the process by which economies evolve.

Economies dependent on external capital, like the unicorn economy, are particularly vulnerable to the bust phase. As I write this, emerging market and energy economies dependent on external capital are scrambling for liquidity.

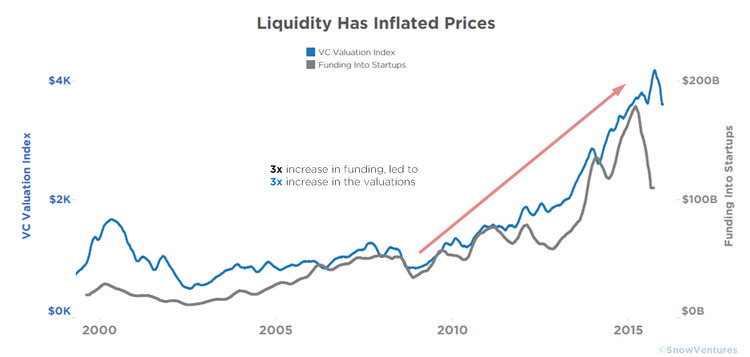

The seeds of today’s bust have roots in the past. In the wake of the financial crisis, the Fed engaged in aggressive easing of monetary policy, to counteract a liquidity crisis in US capital markets.

The goal of this policy was to add liquidity to capital markets, to push up asset prices. This policy was effective, and liquidity found it’s way into the Unicorn Economy, pushing up the valuations for startups. In the heat of the boom last year, funding was flowing into startups at a pace of $150bn a year.

In addition to greater liquidity in the hands of traditional VC players, the Unicorn Economy saw the entrance of ‘cross-over’ investors (themselves fleeing the low returns of public markets) which pushed up prices (and expectations) in the unicorn economy to the point where they can no longer be fulfilled by the majority of enterprises.

Whereas in previous capital cycles, new enterprises would race to turn the corner on the road to profitability and IPO before exhausting unicorn economy capital markets, this new source of capital has enabled enterprises to continue to invest in growth of users without growing revenues.

This leaves the market full of companies creating a lot of value for their users, and capturing little to none of it in the form of revenues, meaning the core question in their business model, whether can they generate cash, has yet to be tested.

This also leaves the unicorn economy deeply vulnerable to conditions in broader capital markets, which look more dire every day. Unless monetary authorities turn face and provide capital markets more liquidity, it looks certain that the Unicorn Economy will face the bust phase of the capital cycle.

This bust phase will not only result in a contraction in spending by firms no longer supported by capital markets, but will lead to a contraction in the broader economy for which these cash flow negative enterprises represent an important source of demand (recall the enterprises for which Sarah is a customer).

Finally, this bust phase will be especially painful not only for those holding their wealth in equity in this economy (without the dual protections of favorable liquidity terms and a diversified portfolio), but those whose life portfolio (jobs, homes or businesses) is tied to this economic ecosystem.

If you carry exposure to this system, we recommend you hedge accordingly.