Don't Invade the Heartland

2,500 Years of Data Explain How To Win From the Periphery

Marcus Licinius Crassus was the richest man in Rome. Member of the First Triumvirate alongside Julius Caesar and Pompey. Made his fortune in real estate and silver mines. Wanted military glory to match his colleagues.

In 53 BC, he invaded Parthia (modern Iraq/Iran) with seven legions—42,000 men.

The Parthians, a Heartland power, drew him deeper into Mesopotamia. At Carrhae, Parthian horse archers surrounded the Romans. The legions formed testudo (shield walls). The Parthians circled, firing arrows for hours.

By sunset: 20,000 Romans dead. 10,000 captured. Crassus beheaded during negotiations.

Later, Parthian King Orodes was watching a Greek tragedy. When the actor needed a prop for King Pentheus’s severed head, someone brought out Crassus’s actual head. The audience applauded.

The richest man in Rome. A theatrical prop. Because he invaded the Heartland.

Timeless and Universal Truths (And Why Most People Get Them Wrong)

“It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” — Thucydides

I remember the day my old boss discovered the Thucydides Trap—Harvard historian Graham Allison’s reframing of the ancient Greek historian’s key insight. The idea: one of the most volatile military situations is when you have two great powers, one rising and one falling, which strains the existing status quo.

Allison’s modern application: “China and the US are currently on a collision course for war.”

What struck me wasn’t the synthesis—sure, it seemed reasonable that conflicts occur when power structures are challenged—but how thin the analysis was.

When I dug into Allison’s study: 16 examples of a rising power challenging a falling power, 12 of which resulted in war.

Not even enough for the Central Limit Theorem. You need at least 30 observations before claiming to know any relationship at 5% significance. Sixteen examples isn’t a dataset—it’s an anecdote with a bibliography.

But my complaint goes deeper than sample size.

When you’re a quant trading stocks, the first lesson is: “past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.” This isn’t compliance boilerplate. The future is, by definition, not like the past—especially when you’re operating on the world based on things you think you know from observations of the past. LTCM learned this the hard way.

The bias appears even in how you select observations. If you’re trading the S&P 500, you’re trading equity shares of very successful companies. Is Lehman in your sample? AIG? All the savings and loans that went bust in the ‘80s/’90s? Probably not.

You’re basing expectations on the winners.

This occurs at the macro level too. When you analyze US stock returns over a century, you’re picking the most successful stock market in history, leaving out all the Argentinas, pre-revolution Russias, pre-WWII Germanys.

So yes, if you cherry-pick the 16 most dramatic conflicts, you’re likely to find big wars where the rising power won and changed the world.

Which got me thinking: If the best analogy for US/China is UK vs. Germany—and Germany was this rising, ethnically homogeneous, recently unified, nationalistic country—why did Germany lose? Twice.

Or, to go back further: Why did Napoleon lose?

These aren’t rhetorical questions. They’re the questions that actually matter if you’re trying to understand great power competition. Because the Thucydides Trap framework tells you when conflict is likely.

It doesn’t tell you who wins or how.

That’s where geography enters.

The Pattern Across 2,500 Years

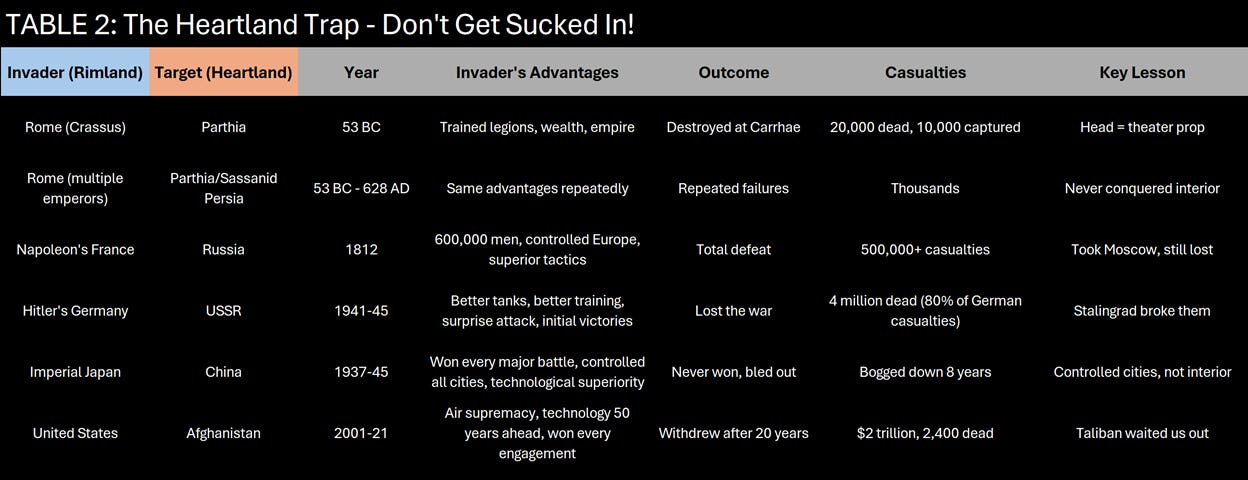

Crassus wasn’t unique. He’s just the most darkly comedic example of a pattern that’s been consistent for millennia.

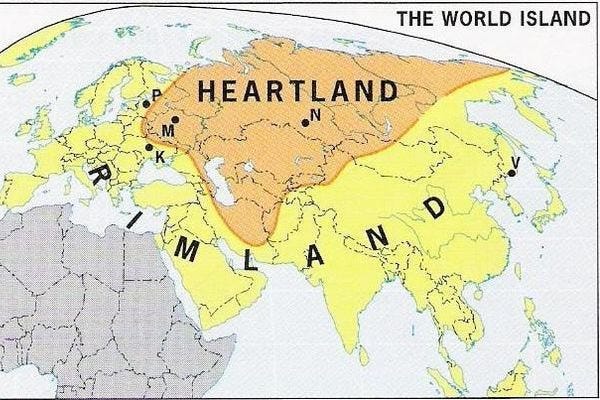

A pattern first introduced at the turn of the 20th century by British historian Halford Mackinder and his theory of the Heartland:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland;

who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island;

who rules the World-Island commands the world.

— Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, p. 106

A straightforward idea—familiar to anyone who’s played Civilization or Command & Conquer. If you control the biggest landmass, you probably win.

Funny thing was, when you looked deeper, this model explained the aspirations of people far more than the outcomes of their attempts at world conquest. A sexy idea, but a poison chalice. It’s led to the destruction of many more empires than it’s created.

Which brings us to why those Heartland empires fell, introduced by American strategist Nicholas Spykman: while lots of folks try to take over the Heartland with dreams of global empire, most of the world’s wealth lies upon the coasts—the Rimland.

Where it’s easy to trade via the sea. Where you find smaller, maritime, commercially oriented societies. This friendliness to trade brings them into contact with other peoples, which liberalizes their society (easy to move around, you get more tolerant when you trade with people who aren’t like you) and introduces potential allies who, coincidentally, also don’t like the idea of someone unifying the Heartland into a world-dominating behemoth.

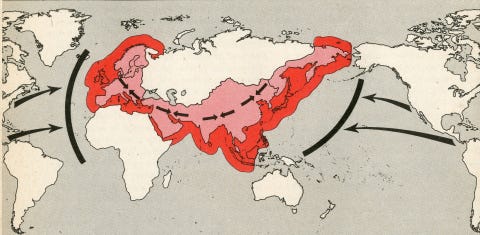

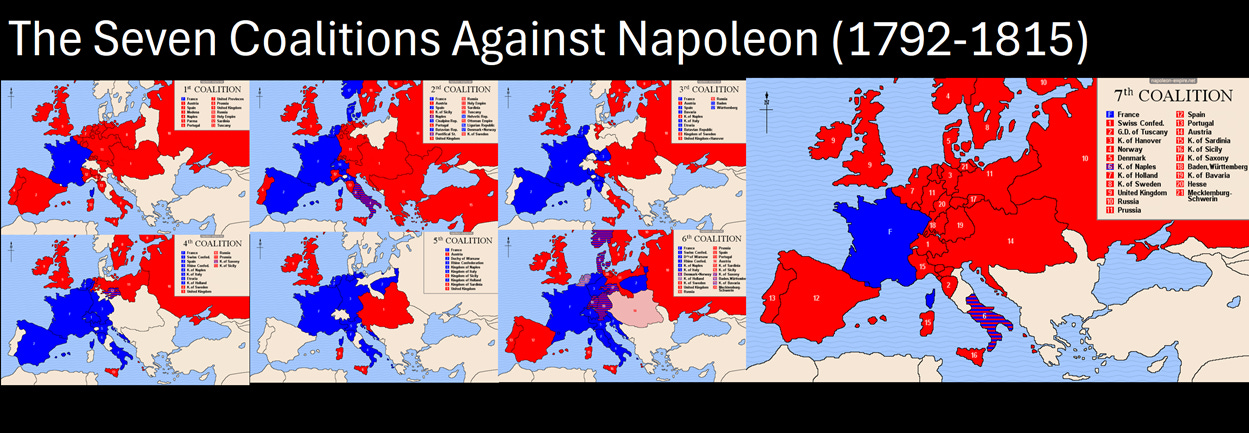

Napoleon being the canonical example. Having been such a menace that it took seven coalitions spread out over 20 years just to chill him out.

Imagine being the British banker raising war bonds to rally the troops for the seventh time (!) in 1815.

Probably sounded similar to one of those decacorns in 2030, raising their Series Q after missing the IPO window: “No, this time we mean it, this is the last raise...”

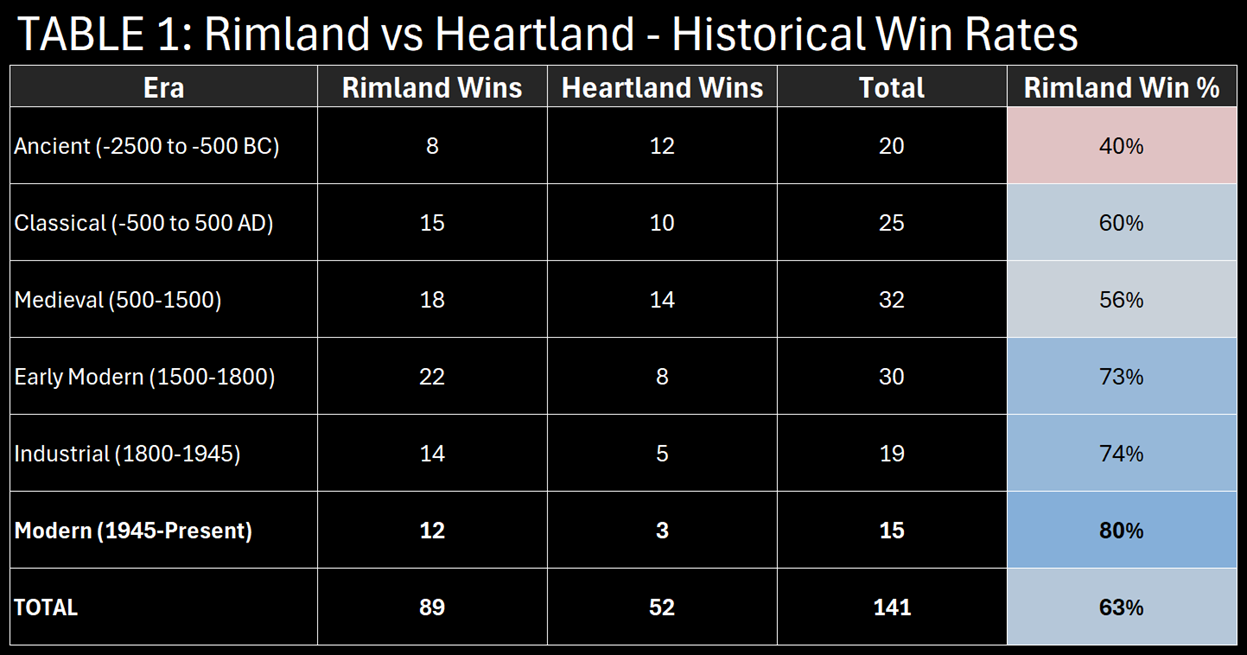

Testing the Theory With Actual Data

Rather than accept conventional wisdom built on cherry-picked examples, I decided to collect some actual data.

What follows is based on a study of 141 major conflicts from 2500 BC to present. For each conflict, we coded which side was the rising power, which was the Rimland/Heartland power, relative size of economies, and relative casualty rates.

Methodology disclaimer: This is the kind of thing someone who actually knows what they’re doing should get paid to compile professionally. I’m an amateur hack here. I asked a bunch of LLMs, cross-referenced historical sources, tried to call out hallucinations, but I’m sure I’ve inserted my own bias and reaffirmed my priors to some extent. But when you see what comes out, it’s directionally sensible.

Five findings emerged:

First: Rising powers almost always win (80%), but rising powers are usually labeled post-hoc, so take this with a truckload of salt.

Second: Rimland powers usually win, though falling Rimland powers lose more often than they win.

Third: Rimland powers win when they rely on their strengths—building alliances, using economic might, containing the Heartland, forcing them to collapse under their own weight. They win with gold.

Fourth: Rimland powers lose in consistent ways—when they overextend deep into the Heartland, where they become vulnerable to extended supply chains, attritional warfare, and encirclement (Napoleon’s march on Moscow, Hitler’s Barbarossa, Alexander in Afghanistan, Crassus at Carrhae).

Fifth: Heartland powers usually win with blood—trading space and bodies for time (Alexander I against Napoleon, Stalin against Hitler, China against Japan in WWII).

The pattern is overwhelming: Rimland powers win by controlling the periphery. They lose by invading the interior.

The Data: Win Rates Over Time

We analyzed 141 documented conflicts from 2500 BC to present, coding each for geography (Rimland vs Heartland), power trajectory (rising vs falling), and outcomes. The pattern is overwhelming.

Rimland powers (sea-based, trade-oriented, alliance-driven) win by controlling the periphery. They lose by invading the interior.

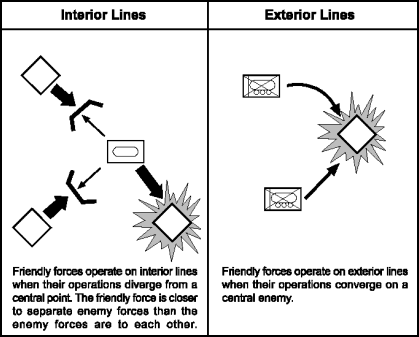

The trend is unmistakable, and the Rimland advantage has grown over time. In ancient times, Heartland powers actually won more often (60%). Land-based empires—Persians, Assyrians, Mongols—could project power through sheer manpower and interior lines.

By the Industrial Age, Rimland powers were winning 74%. Railroads and telegraphs helped Heartland powers mobilize, but maritime logistics were already superior.

Since 1945: Rimland powers win 80% of conflicts.

But the modern era is different in a more fundamental way. Rimland powers don’t just win more often—they win at a fraction of the cost.

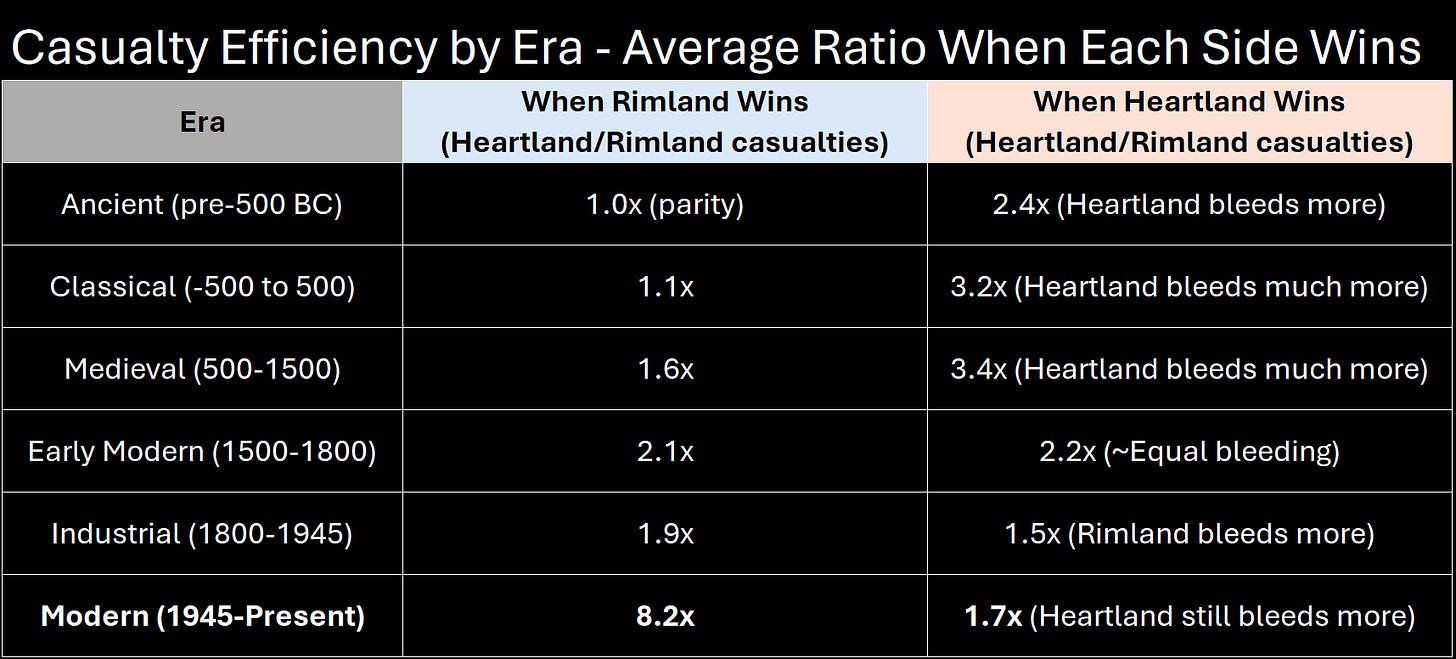

The Efficiency Gap

Here’s the part nobody talks about: It’s not just that Rimland powers win more often. It’s that they win more cheaply.

We analyzed casualty ratios* across 141 historical conflicts. The key insight: economic size doesn’t determine victory. Strategy does.

And here’s how strategy manifests in blood: for every Rimland casualty, how many Heartland casualties?

The results are intriguing, though probably worth double checking.

What the data shows:

When Rimland powers win:

Modern era (1945+): They inflict 8-10x more casualties than they take

Historical average: 3-5x casualty advantage

Examples: Gulf War (100:1), Kosovo (0 NATO combat deaths), Libya (0 coalition casualties)

When Heartland powers win:

They still bleed heavily—often taking MORE casualties than opponent

Win through endurance and attrition, not efficiency

Examples: USSR in WWII (8.7M military deaths to beat Germany), Russia in Chechnya (massive casualties to “win”), China in Korea (300K+ deaths for stalemate)

Napoleon’s Fatal Mistake (And Everyone Who Followed)

The pattern repeats. Rimland power invades Heartland with every advantage. Wins initial battles, can’t force decisive victory. Gets ground down by depth, time, logistics, nationalism, climate, attrition. Eventually loses.

Historical win rates when strategies diverge:

Rimland powers avoiding invasion of Heartland interior: 81%

Rimland powers invading Heartland interior: 10%

Technology changes. The outcome doesn’t.

Every invader thinks it’ll be different. They always have good reasons. Their military is overrated (Parthian cavalry vs Roman legions, Russian feudal army, Stalin’s purges, Chinese military backward, Taliban had rifles vs F-18s, PLA untested since 1979). Their economy is collapsing (Parthia fragmenting, Russian serfdom failing, Soviet collectivization disaster, Warlord chaos, Afghanistan had no economy, China’s property crisis bleeding $1.1T/year). Their regime is illegitimate (Parthian despotism, Tsarist autocracy, Communist terror state, Warlords/KMT corruption, Taliban oppression, CCP authoritarianism). We have better technology (Roman engineering, French artillery, Panzers and Luftwaffe, Planes and tanks vs horses, Drones and precision weapons, F-35s and carriers).

All of these can be true. You still lose.

Heartland advantages aren’t about strength—they’re about making you weak. Depth means they retreat, you advance, your supply lines stretch. Time means they wait, you need results (domestic political pressure: “Why are we still there?”). Attrition means you win battles, they lose but survive to fight again (no decisive engagement). Nationalism means they’re defending homeland, you’re foreign invader (rallying effect). Logistics means your high-tech equipment breaks in their climate, their simple weapons don’t (T-34 tanks worked in -40°C; German panzers froze). Climate and terrain—winter, disease, mountains, distance—exhaust you.

The Heartland doesn’t win by being strong. It wins by making you weak.

Napoleon took Moscow. Still lost. Hitler almost took Stalingrad. Still lost. Japan took Nanking, Shanghai, Wuhan. Still lost. US took Kabul in weeks. Still withdrew after 20 years.

Controlling cities isn’t winning. The Heartland wins by not losing—by surviving until you give up.

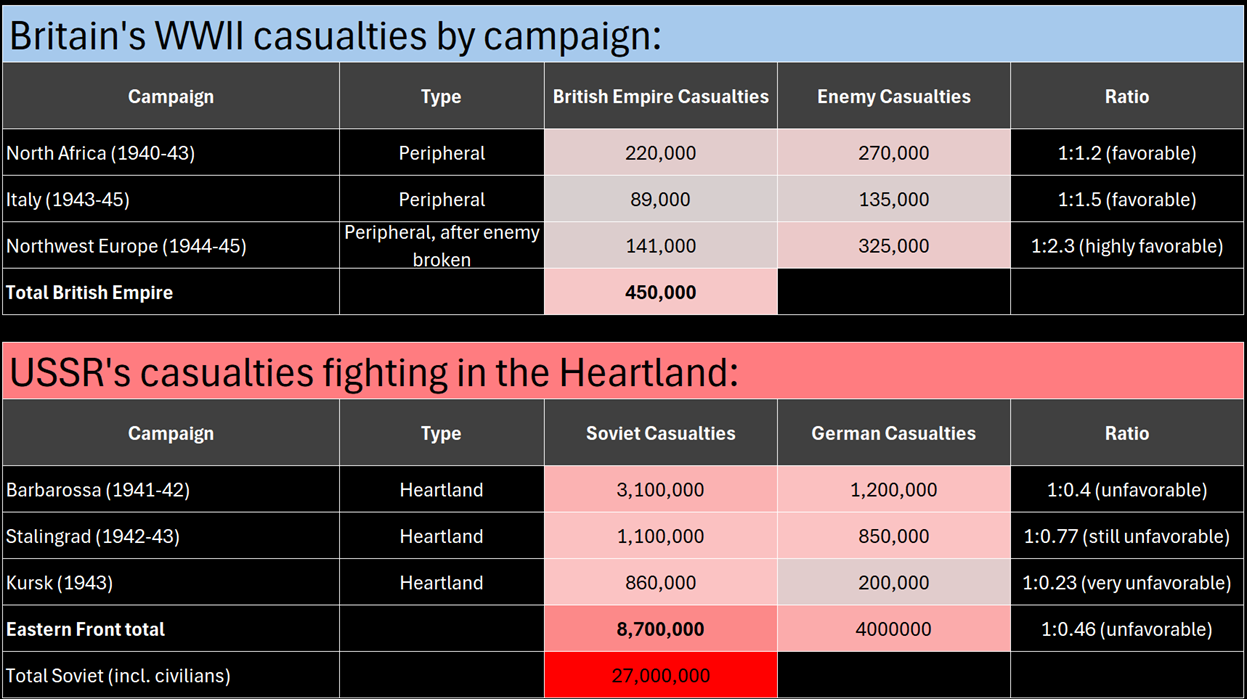

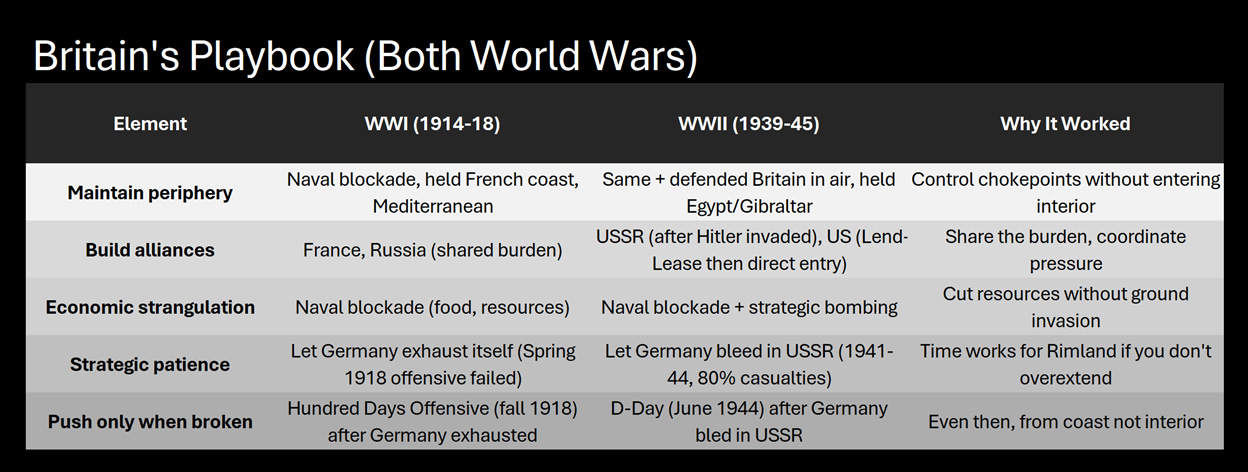

The Good and The Bad: Britain’s Playbook vs. Germany’s Trap

Britain: How to Win From the Periphery (Both Wars)

World War I: Britain never invaded Germany. They blockaded, they built alliances, they waited. The Royal Navy strangled German trade. By 1918, German civilians were starving. The economy collapsed. The army mutinied. Germany sued for peace—not because they lost battles, but because they ran out of food, fuel, and money.

British casualties: 886,000 military deaths German casualties: 2,037,000 military deaths

Britain bled less, spent more time, and won.

World War II: Churchill’s strategy from 1940-1944: Don’t invade Europe until Germany bleeds out in Russia. North Africa, Italy, strategic bombing—all peripheral operations. Keep pressure, but don’t commit to decisive battle until the enemy is already broken.

D-Day happened June 1944—after three years of Germany bleeding in the East. After Stalingrad. After Kursk. After the Wehrmacht was already shattered. Churchill invaded when Germany couldn’t fight back effectively.

The Rimland powers combined lost less than 1 million. The Heartland power fighting Germany in the interior lost 10 times that. Both won. One did it at 1/10th the cost.

The Britain Playbook:

1. Never invade the Heartland

2. Build alliances (France, Russia, eventually US)

3. Apply economic pressure (blockade, sanctions)

4. Wait for the enemy to exhaust themselves

5. Only push when they’re already broken

Boring. Politically difficult. Unglamorous. But it works.

Germany: The Fatal Pattern (Both Wars)

World War I (1914-1918):

Germany’s strategy was actually smart initially. The Schlieffen Plan: knock out France quickly (6 weeks), then turn and face Russia.

They almost succeeded. Got within 30 miles of Paris (September 1914). Then the French counterattacked at the Marne. Trench warfare began.

Germany got bogged down on the Western Front. Two-front war—France/Britain in the west, Russia in the east.

Then 1917: Russia collapsed. Bolshevik Revolution. Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918) gave Germany control of Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic states. Germany won the East.

At this point, Germany could have:

· Consolidated control of Eastern Europe

· Shifted to defensive posture in the West

· Waited for Britain/France to exhaust themselves

· Negotiated peace from position of strength

Instead: Spring Offensive 1918. One last push to knock out France before American troops arrived in force.

The offensive failed. Germany exhausted its reserves. The Allies counterattacked (Hundred Days Offensive, summer-fall 1918). Germany collapsed by November.

Lesson: Even when they won the East, they couldn’t resist overextending for the knockout blow.

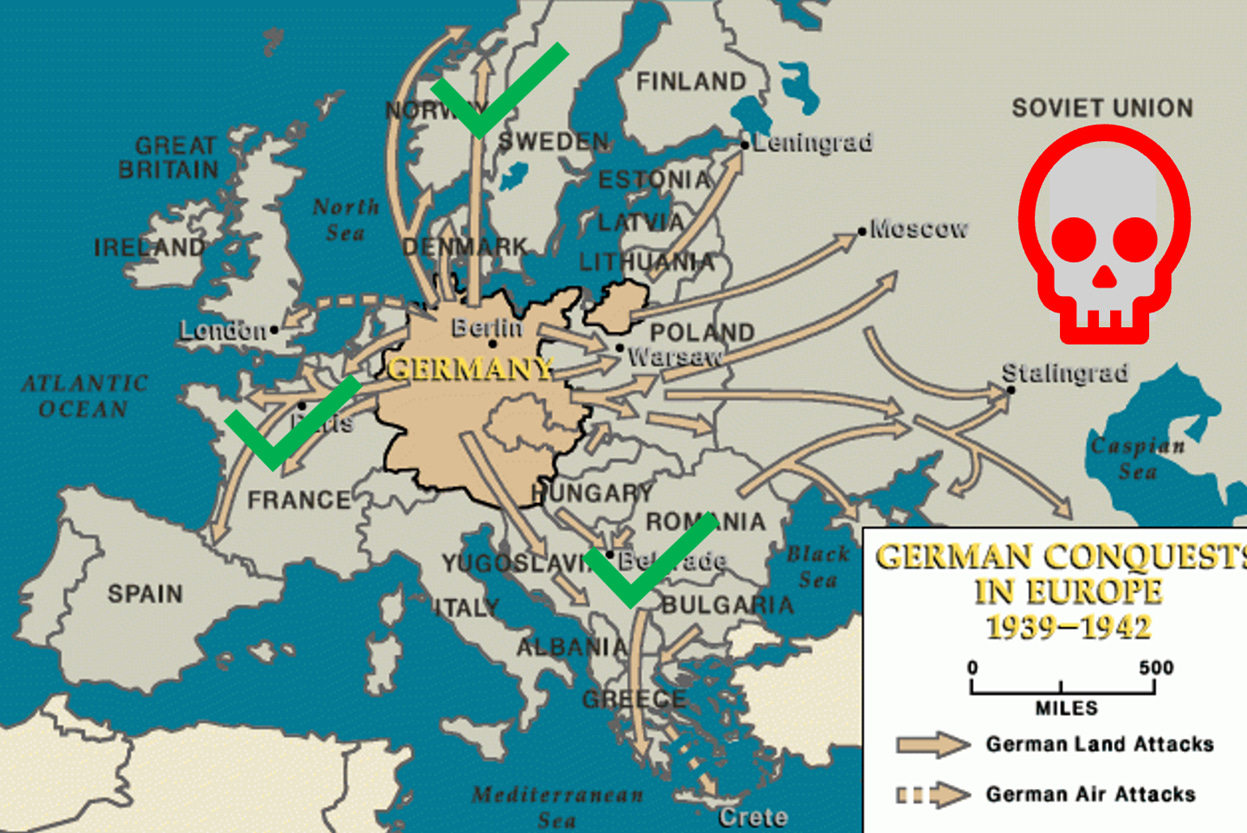

World War II (1939-1945):

Germany’s early success came from staying on the periphery. Quick strikes, consolidate, move on.

The Periphery Strategy (1939-1941):

· Poland: 5 weeks (Sep-Oct 1939)

· Denmark/Norway: 2 months (Apr-Jun 1940)

· France: 6 weeks (May-Jun 1940)

· Balkans: 3 weeks (Apr 1941)

Germany was winning. By spring 1941, they controlled Poland, France, Low Countries, Denmark, Norway, Balkans. Allied with Italy, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria. Non-aggression pact with USSR.

Germany could have stopped. Consolidated. Defended. Britain was isolated (US not yet in war). USSR was neutral.

But Hitler couldn’t resist.

June 22, 1941: Operation Barbarossa.

3.8 million men. Largest invasion in history. Three army groups. Objective: Destroy USSR in 3-4 months before winter.

Hitler’s logic (like every invader before him):

· Soviet military is weak (TRUE—Stalin’s purges destroyed officer corps)

· Soviet economy is collapsing (TRUE—collectivization was catastrophic)

· Soviet regime is illegitimate (TRUE—terror state)

· Soviet people will welcome us (PARTIALLY TRUE—some Ukrainians did initially)

· We have better technology (TRUE—German tanks, tactics, training superior)

· It’ll be over quickly (FALSE)

What happened:

1941-42: The Trap Closes

· Winter: Unprepared for -40°C, equipment froze

· Supply lines stretched: Moscow 1,000 miles from German border

· Soviet resistance stiffened: Defending Motherland, not Communist Party

· Partisans behind German lines: Classic Heartland defense

1942-43: Stalingrad

· German 6th Army (300,000 men) encircled

· Hitler refused retreat, entire army destroyed

· Turning point—Germany never recovered

1943-45: Soviet Counteroffensive

· USSR pushed Germany back through Eastern Europe

· Red Army in Berlin, April 1945

80% of German casualties were on the Eastern Front.

The war in Western Europe—North Africa, Italy, France—was the sideshow. The real war, the war that killed Nazi Germany, was in the Heartland.

The Pattern

Britain (both wars): Never invaded the Heartland. Built alliances. Applied economic pressure. Waited. Pushed only when the enemy was already broken.

Result: Won both wars with minimal casualties relative to Heartland combatants.

Germany (both wars): Started with peripheral success. Consolidated control. Then couldn’t resist the temptation to invade deep into the Heartland for the decisive victory.

Result: Lost both wars, bled catastrophically in the attempt.

The data doesn’t lie. The pattern is consistent.

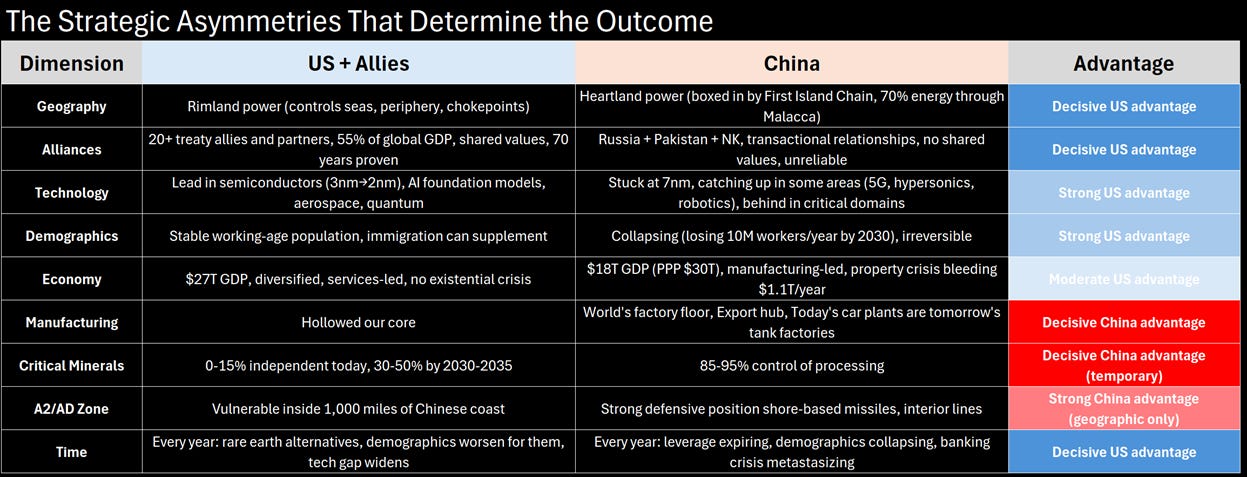

The Alliance Asymmetry (Why They Can’t Win Long-Term)

China sucks at making friends. This isn’t a small problem—it’s the fundamental structural disadvantage that makes their strategic position untenable long-term.

The US Alliance Network: 70+ Years in the Making

Japan: 54,000 US troops stationed, mutual defense treaty, integrated command structures, technology partnerships (co-developing next-gen fighters).

South Korea: 28,000 US troops, mutual defense treaty, coordinated defense planning. Samsung, SK Hynix memory chips deeply integrated with US tech ecosystem.

Australia: AUKUS nuclear submarine partnership, Pine Gap intelligence facility, force interoperability.

Philippines: Mutual defense treaty, recently restored base access (2023).

Thailand: Treaty ally since 1954.

India (Quad member, shared China concern, military exercises, technology cooperation, massive market, manufacturing alternative to China.

Singapore (US naval presence, intelligence cooperation, financial hub leaning West).

Vietnam (enemy of my enemy, South China Sea disputes with China, buying US weapons).

Taiwan: TSMC produces 90% of advanced chips, fully aligned with US.

Netherlands: ASML extreme ultraviolet lithography machines, only source for cutting-edge chip production.

USMCA: US-Mexico-Canada, $1.3T annual trade.

European Union: $1.1T annual trade.

Combined: ~55% of global GDP aligned with US interests

China’s “Alliance” Network: Transactional, Not Strategic

Russia: “No limits partnership” announced February 2022, weeks before Ukraine invasion. Reality—Russia is junior partner, economy smaller than Italy’s. This is a pact between declining powers, not an alliance of strength.

Pakistan: $62B in Belt & Road investment, creating dependency not partnership. Pakistan is liability (economic basket case, terrorism safe haven, nuclear-armed instability).

North Korea: China provides 90% of energy, most food. Kim does whatever he wants regardless of Chinese preferences—it’s babysitting a dangerous toddler with nukes.

Belt & Road “Partners”: $1 trillion invested, countries now heavily indebted. When they can’t pay, China seizes strategic assets (Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka). Result: growing backlash, not gratitude. These are resentful debtors, not grateful allies.

BRICS: No mutual defense commitments, no integrated command, no technology sharing. Members have completely different interests (India is simultaneously in the Quad with the US and antagonistic toward China).

Iran: China buys Iranian oil at discount prices. Religious theocracy and atheist communist state have nothing in common beyond opposing the US.

Combined: ~30% of global GDP (mostly China itself), no real allies

The One Phone Call Test

US makes one phone call to Japan: “We need Okinawa bases operational, Fifth Air Force deployed, AEGIS destroyers in formation.” Response within 24 hours: “Already done. What else do you need?”

To South Korea: “We need Osan and Kunsan at full capacity.” Response: “Airbases are yours. Deploying missile defenses. What else?”

To Australia: “We need Pine Gap intelligence, submarines in South China Sea.” Response: “You have it. Activating AUKUS protocols.”

This is rehearsed. We’ve done variations for 70 years.

China makes the same call to Russia: “We need military support.” Response: “What’s in it for us? We can sell you weapons at premium prices, but direct involvement? Different negotiation.”

To Pakistan: “Threaten India, tie down their forces.” Response: “If India attacks you, we’ll respond for our interests. But fight the United States? We’re not suicidal.”

To North Korea: “Threaten South Korea and Japan.” Response: [Unpredictable. Kim might. Or might not. Or might make everything worse.]

Within weeks, the US has 5+ carrier strike groups in theater, allied air forces flying coordinated missions, real-time Five Eyes intelligence, and logistics spanning the entire Pacific.

China has shore-based missiles, their fleet, and ground-based air force—and that’s it. No allied bases, logistics, intelligence, or coordinated support. They’re alone.

You can buy clients. You can’t buy allies.

Alliance-building requires trust (70 years of kept commitments), shared values (democracies cooperate naturally), mutual benefit (genuine partnership), and time (US-Japan alliance: 70+ years; China-Russia “partnership”: 10 years and transactional).

This gap cannot be closed in the 2025-2030 window. Trust takes generations. China doesn’t have generations.

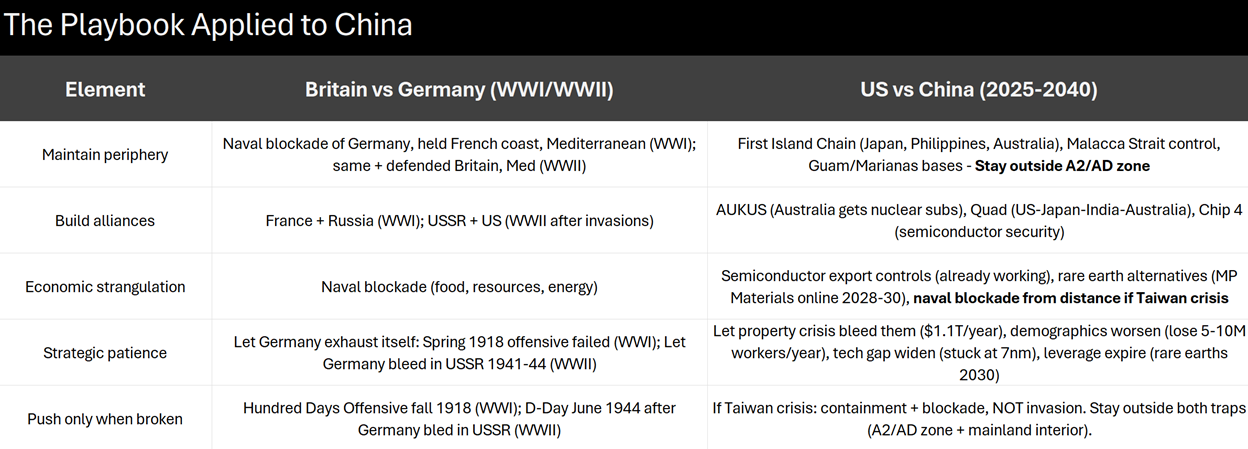

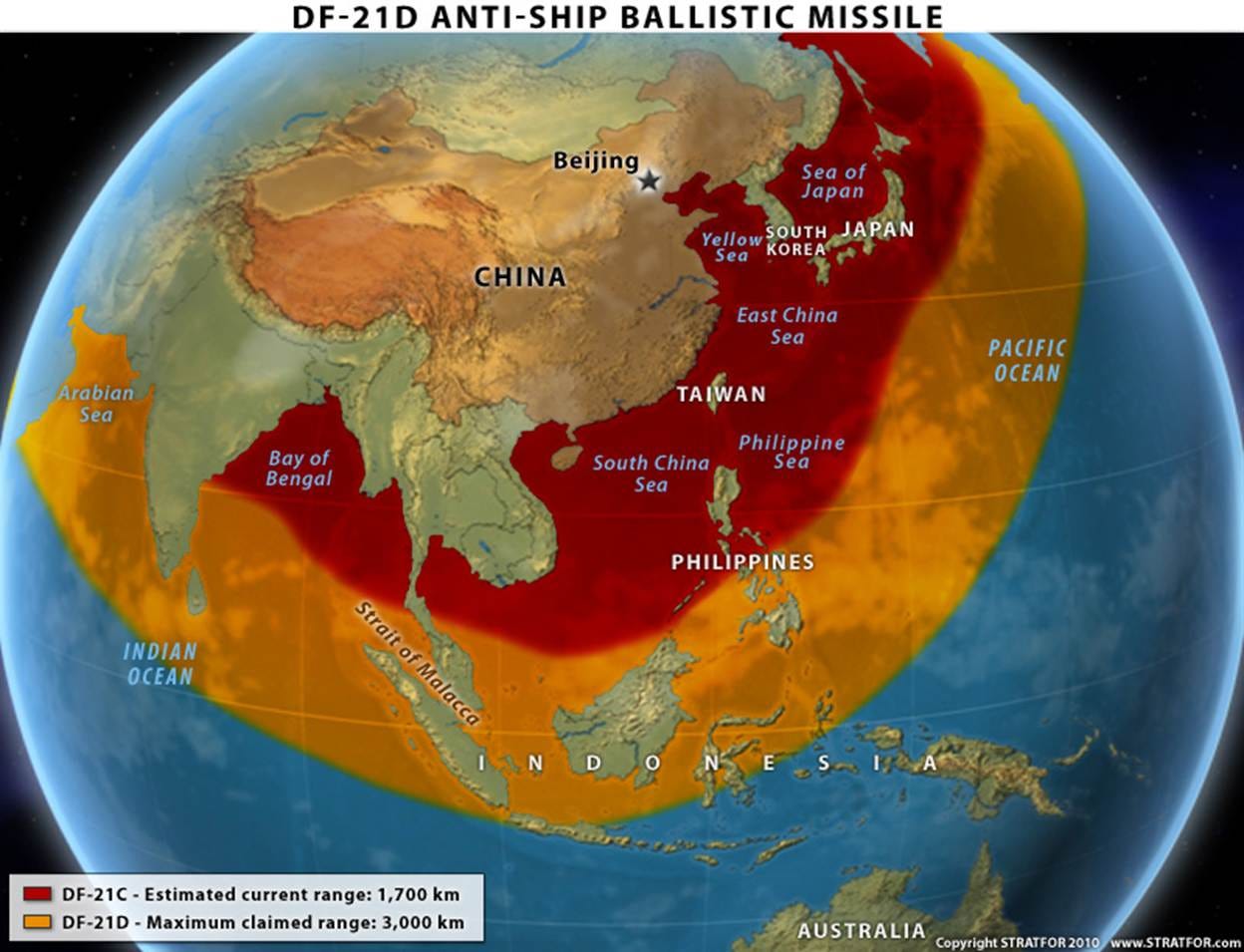

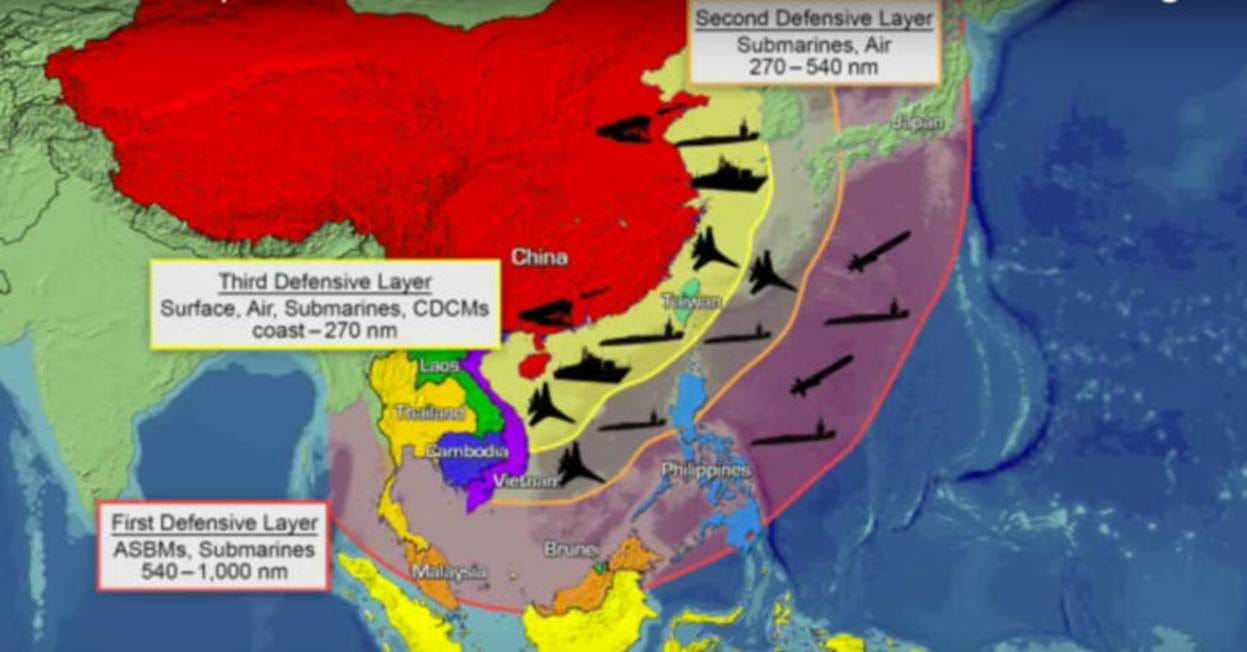

The Modern Heartland: A2/AD as Interior Depth

Taiwan isn’t just about the island—it’s about where the island sits. Taiwan is 100 miles from mainland China, inside China’s A2/AD (Anti-Access/Area Denial) envelope.

The traditional Heartland trap was about interior depth—invading into land where the defender has advantages. The modern Heartland trap includes the A2/AD zone where shore-based weapons create a defensive bubble extending 1,000+ miles from the coast.

China’s A2/AD isn’t about conquering the Pacific—it’s about survival. A US naval blockade cuts off 70% of energy imports through Malacca Strait, 100M tonnes of food imports, and 90% of seaborne trade.

China’s response: DF-21D and DF-26 “Carrier Killer” missiles (ranges of 1,000+ and 2,500+ miles), 50+ attack submarines patrolling near seas, shore-based aircraft with 5-10 minute flight times from Fujian province, and artificial island bases in the South China Sea pushing the defensive perimeter outward.

The purpose: make it costly enough for the US to operate within 1,000 miles of Chinese coast that we give up. Not beat the US Navy outright—just deny access long enough.

Traditional vs Modern Heartland:

Traditional: Defender has interior lines. Attacker faces stretched logistics. Deeper you go, weaker you get. Defender trades space for time.

Modern A2/AD: Defender has shore-based missiles. Attacker faces carriers at risk. Closer you get, more vulnerable. Defender denies access, raises costs, waits for domestic pressure.

Just as you don’t invade deep into Russia’s interior, you don’t fight sustained naval operations deep inside China’s A2/AD envelope.

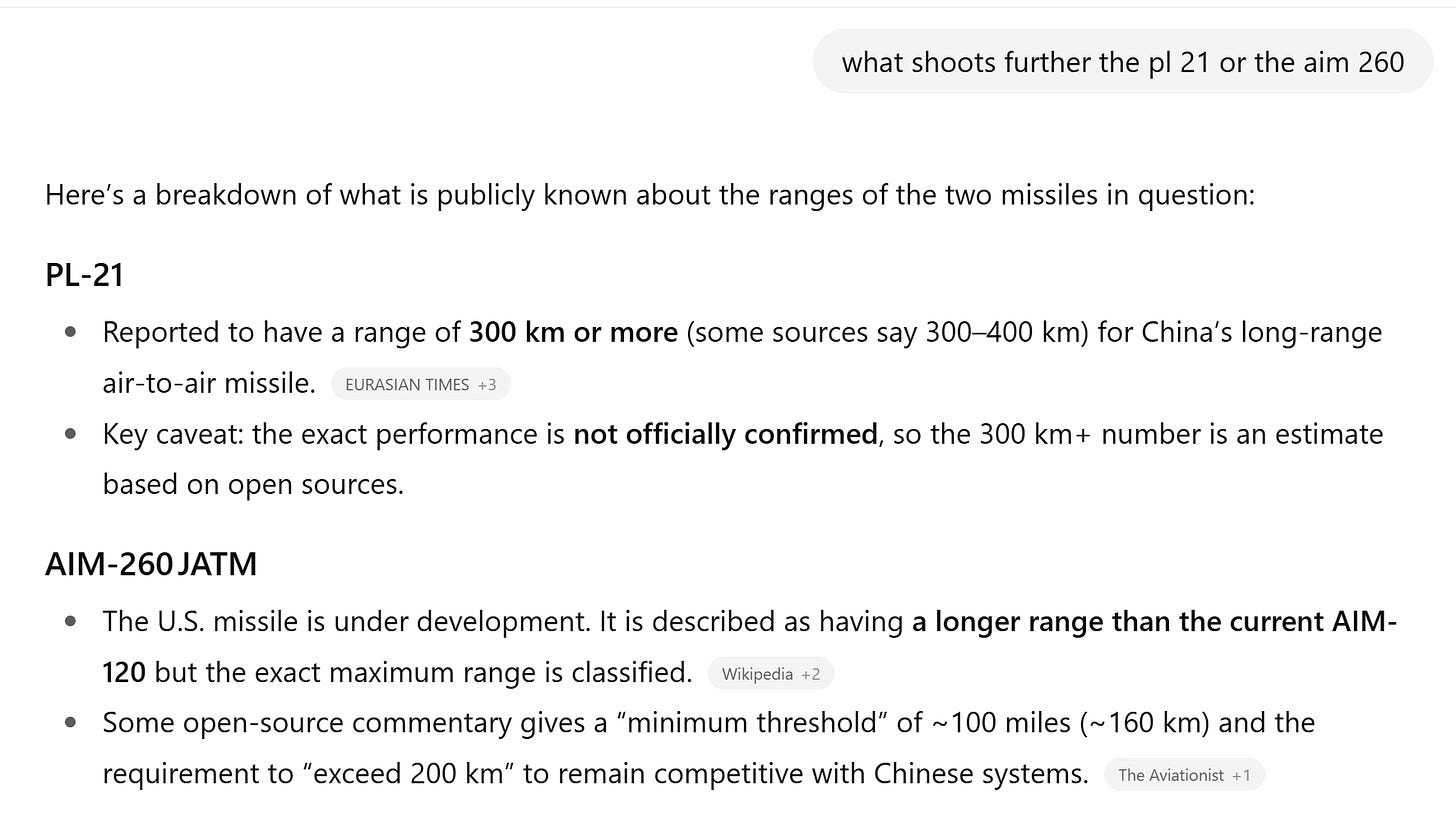

Taiwan sits 100 miles from mainland China—within DF-21D range, within DF-26 range, within Chinese submarine patrol areas, within 5-10 minute flight times from shore bases. That’s before we get to the part where their air-to-air missiles may shoot further than ours.

Fighting there means fighting in their Heartland equivalent.

How we lose

Let me be specific about mistakes that would turn our structural advantages into defeat.

Fighting in the A2/AD zone: Sending carriers within DF-21D range (inside 1,000 miles of Chinese coast), trying to “break the blockade” of Taiwan by sustained naval operations in contested waters. Result: carrier casualties, massive domestic pressure for escalation, taking the bait. The data shows what happens when Rimland powers invade Heartland interiors—win rate drops from 80% to 10%, casualty ratios reverse from 8:1 favorable to 1:3 unfavorable.

Escalating to mainland strikes deep inland: After inevitable losses in A2/AD zone, political pressure to “strike back harder,” hitting command centers in Beijing, infrastructure deep in interior. Result: now you’re fighting on their territory, supply lines stretched, Heartland trap springs shut. Even when invaders “win” such campaigns, they bleed catastrophically. USSR: 8.7M military deaths beating Germany in the Heartland. China: 300K+ casualties in Korean War for a stalemate. Russia: 200K+ casualties in 2 years in Ukraine. Modern Rimland victories fought from the periphery: Gulf War with 100:1 casualty ratio and 100 hours of ground combat, Kosovo with zero NATO combat deaths, Libya with zero coalition casualties. The math doesn’t care about honor or resolve. It cares about geography and logistics.

Abandoning allies: Pulling back to “Fortress America” isolationism, breaking AUKUS commitments to save money, signaling that Taiwan is “on its own.” Result: alliance structure collapses, our 20-vs-1 advantage becomes 1-vs-1.

Not fixing vulnerabilities: Environmental reviews delay rare earth projects for 5+ years, 2030 arrives and we’re still 90% dependent on Chinese processing. Result: Taiwan crisis happens while we’re vulnerable to supply cutoff.

Any of these turns our 81% win probability into a coin flip.

The Urgency Paradox

We need strategic patience (don’t take the bait) AND tactical urgency (fix vulnerabilities now). Both are true. Different timeframes.

Strategic patience (10-20 year view): We’re winning the long competition. Time works for us (demographics, technology, alliances all favor us). Don’t rush into fights where geography favors them. Let their internal contradictions (debt, demographics, despotism) work against them. Only push when they’re already broken (like D-Day after Germany bled in USSR).

Tactical urgency (2-7 year view): Their window is 2025-2030. We need to be ready before it closes. Rare earth alternatives must be online by 2030 (processing plants take 3-5 years to build). Alliance commitments honored (AUKUS submarines delivered on schedule). Critical mineral stockpiles built (6-12 month reserves for defense production). Immigration reform to keep talent here (every Chinese PhD who stays is a PhD they lose).

The synthesis: be patient strategically (don’t invade their Heartland, don’t fight in A2/AD zone except when absolutely necessary), be urgent tactically (fix vulnerabilities before their window closes), recognize 2025-2030 is when both dynamics collide—their last good opportunity coincides with our greatest vulnerabilities if we don’t act now.

The Takeaway

Across 2,500 years of history, the pattern is clear:

The power that stays mobile, maritime, and allied wins. The one that marches into the Heartland loses.

Empires don’t die in battle—they die in overreach.

The Heartland consumes invaders the way deserts consume water and winters consume armies. Logistics fail. Coalitions fracture. Time works against you.

In numbers: Rimland coalitions win roughly three out of four great wars. They do it with fewer casualties, greater trade leverage, and higher GDP share.

The lesson is not just geography—it’s structure. Open systems defeat closed ones because they can adapt, trade, and regenerate.

So don’t invade the Heartland.

Contain it, encircle it, and let it collapse under its own weight.

That’s how Athens beat Persia, how Britain beat Napoleon, how America beat the Soviets—and how the next Rimland power will win again.

What’s Next

Chapter 4 established how geography, alliances, and strategy interact across 2,500 years of conflict. We have the structural advantages. They’re in a closing window (2025-2030). If conflict comes, we win by not taking the bait—but only if we execute.

Execution requires two things. First: a strategy for applying peripheral pressure without triggering the Heartland trap. What does “chaos from position of strength” actually look like in practice? How do you force them into impossible choices without starting a war you don’t want? Second: fixing our vulnerabilities during the 2025-2030 window. Critical minerals, technology gaps, manufacturing capacity—what needs to happen before their window closes?

Chapter 5: Chaotic Containment shows you the first part. The strategy. The game theory. How to make them choose between bad options while we maintain optionality. Including one specific proposal so audacious it sounds insane—until you see the math and game theory behind it.

Chapter 6: Our major vulnerabilities.

The good news: everything in Chapters 6 is fixable with money and political will.

The bad news: we’re not moving fast enough yet.

Crassus thought Parthia would be different. Hitler thought Russia would be different. Every invader thinks it’ll be different. The math says otherwise. Let’s make sure we don’t become the next theatrical prop.

Disclaimers

Charts and graphs included in these materials are intended for educational purposes only and should not function as the sole basis for any investment decision. Opinions contained herein are solely my own and do not represent the views or perspective of any of Rose Technology’s clients, investors, or counterparties.

This letter does not constitute an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security. Nothing herein is intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice. You are solely responsible for determining whether any investment, strategy, security or transaction is appropriate for you. Consult your business advisor, attorney, or tax professional.

THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT INVESTMENT OBJECTIVES WILL BE ACHIEVED OR STRATEGIES WILL BE SUCCESSFUL. PAST RESULTS ARE NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. AN INVESTMENT INVOLVES A HIGH DEGREE OF RISK, INCLUDING THE RISK THAT THE ENTIRE AMOUNT INVESTED IS LOST.

This is a great analysis, but I have serious concerns about US state and fiscal capacity that make me hesitant to fully agree.

You’ve mentioned before the implied bargain that Beijing has struck with the Chinese people: we keep you prosperous, but we stay in power.

I’m not sure that a similar dynamic doesn’t exist in USA at this point. A lot of the people who live here simply do not seem to like the country very much, and how far any government can count on them if their 401Ks crash and/or their benefits are reduced is debatable, at minimum.

FDR never had to worry about a giant pre-existing debt overhang.

And we didn’t just send the physical factories to China. We also surrendered a lot of the muscle memory you need to build things, period. You’re not fixing that in 5 years, especially if resources are constrained and you lack essential ingredients.

I look forward to the next chapter.

I am pretty confident that in your conflicts sample of 141 they're maybe 2 to 10 that are comparable to a conflict like China to USA.