Where Did All the Lamplighters Go?

Automation and the Information Economy

Six months ago, we took a couple thousand words to answer the question “Where Did All the Farmers Go?”

I’ll save you the trouble, the answer was machines.

Machines and SaaS.

The longer story is that farmers have been supplementing their labor with animal power for millennia. Water power led to wind power, which eventually led to the engine. This technological progression unlocking a myriad of machines that replaced human and animal labor with steel, petroleum, and microchips — a trend that continues to this day.

In fact, this proliferation of machines (and modern fertilizer) is actually how we managed to feed 8bn people.

In spite of doomers like Malthus that said there wasn’t enough land on earth!

You can see the radical improvements in the fruit of our labor that broke Malthus’ model below. All we needed was a 5x improvement in the yield of carbs and boom, there goes his model. Reminds me of energy today, in a way, but that’s a story for another ramble.

This improvement in agricultural productivity was not only a boon insofar as it led to a world capable of feeding 10bn humans, but also because of all the time it freed up.

As Sam Altman put it recently, in a world with electric lighting, being a lamplighter is a “trifling waste of time.”

In this context, the agricultural revolution was amazing not just because the price of food went down to the point where 10bn people became easy, but because it freed up all those well fed people to now do other things aside from grinding out dinner. You know things like spreadsheets and powerpoint.

Freeing up from billions from subsistence agriculture is probably the single most important output of industrialization. So far. (Remember this is all an allegory for what happens when human level robots show up in 3…2…1…)

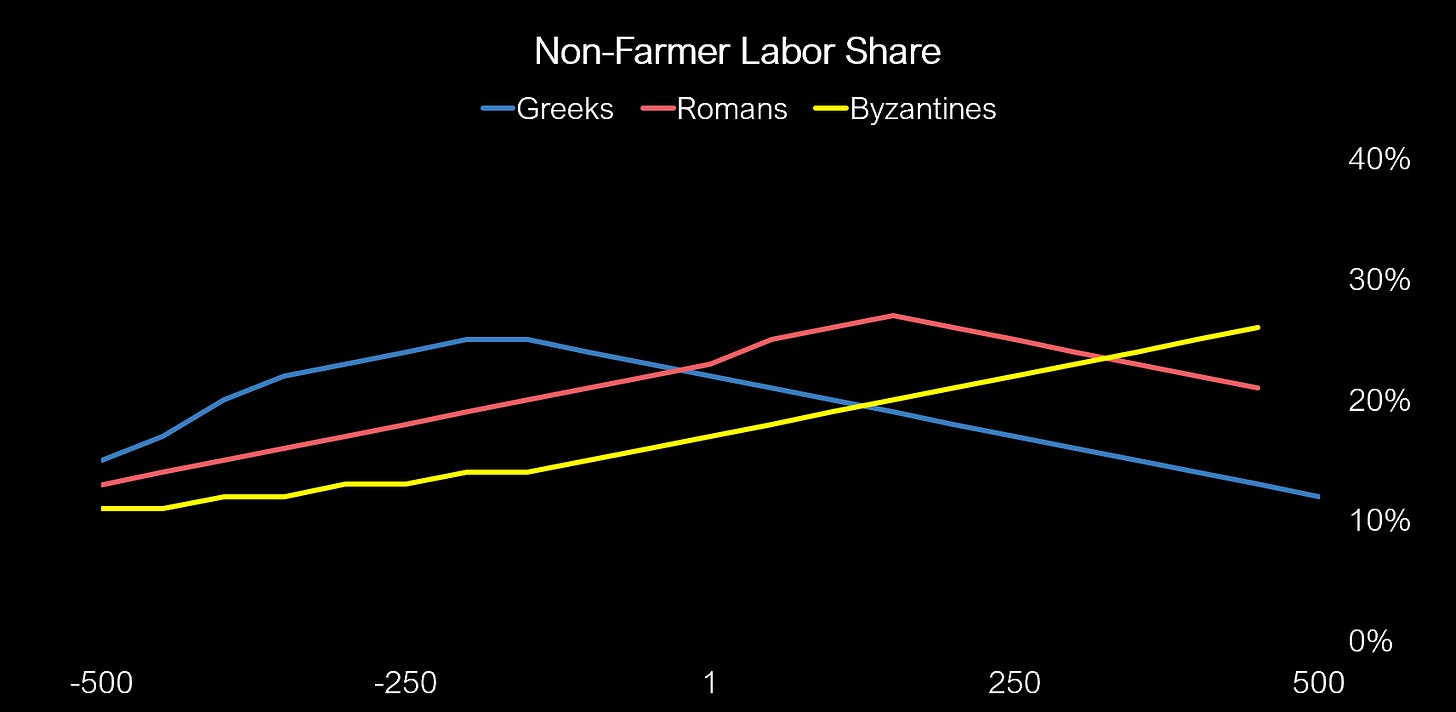

Interestingly, the chart above reveals the peaks of classical civilizations through the proportion of people engaged in non-agricultural work.

So if even the job of ‘farmer’ has no intrinsic good, insofar as it’s good when a lot of people are doing other non-farming stuff, why would we want to ‘protect’ that job?

With the power of hindsight, why would you want to protect any of the jobs from our list of prior automation?

Also, look at how many new jobs were born out of the ashes of what was automated.

In the modern context, we see the dockworkers that might get automated when they go viral, but we don’t see the jobs created designing, manufacturing, maintaining, and supporting the machines that will replace them.

We don’t see the other new jobs that open up once the cost of shipping goes down. At least not yet.

If you are a markets person like me, you look at that list up above and go “huh there seems to be a lot of turnover in the way we create and store information.”

Which kind of makes sense with an eye towards history. After all, most of the first major examples of ancient writing were concerned with trade, property, contracts, inheritance, taxes. In short, money.

For example, the majority of Hammurabi’s Laws had something to do with money.

Gets you thinking about the guys that introduced papyrus as a disruptive technological revolution over hammering reeds into clay tablets.

Imagine if, instead of logging into Yelp, you had to sit down with wet clay and a stylus to record your dissatisfaction with 1,080 pounds of copper (worth about $5,000 at today's prices, or roughly a month's average wages at the time, paid in bags of barley called "sila").

Which, if you are a data nerd like me, gets you thinking about where can I find this process of automation via capital in long term macro stats?

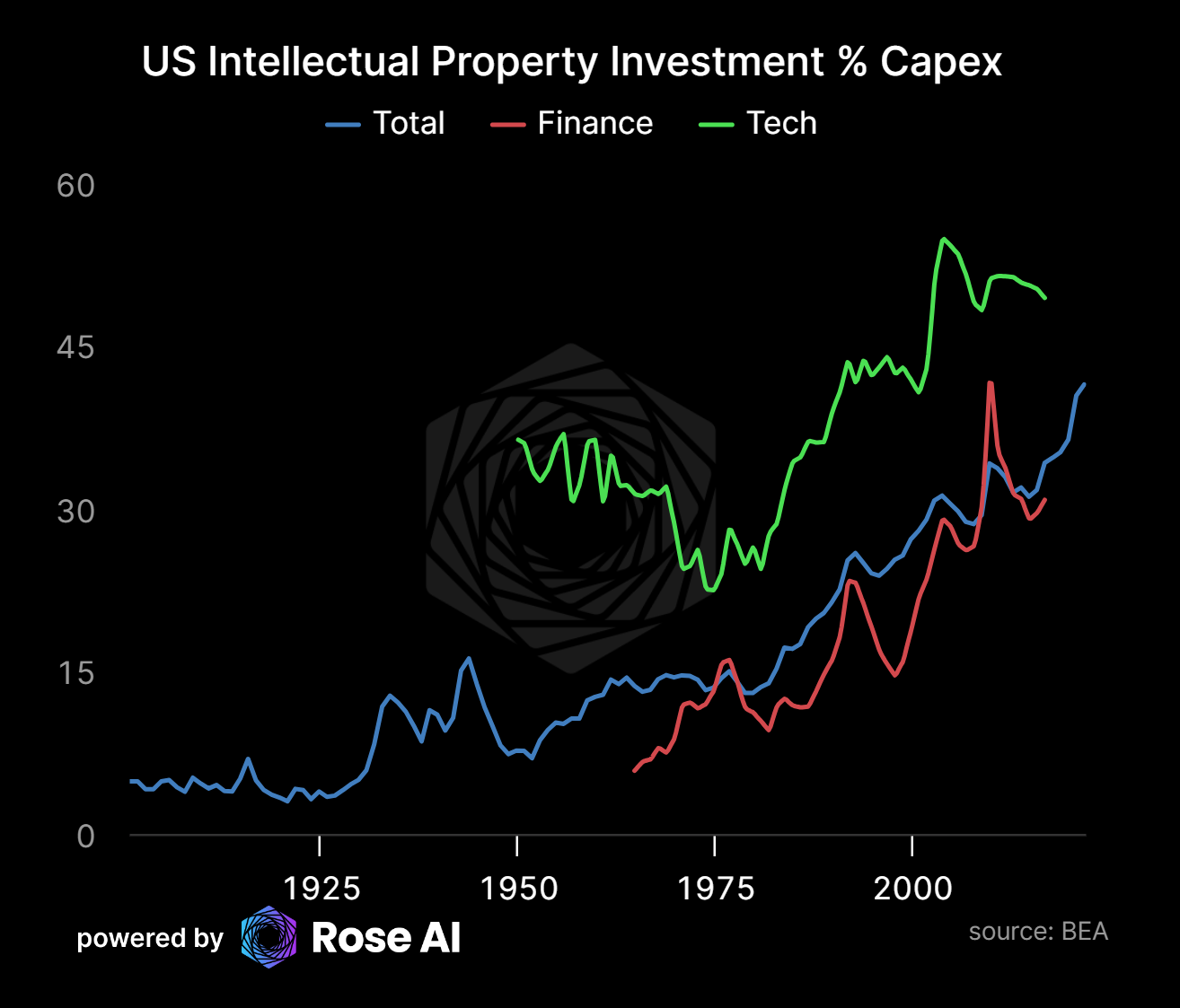

So you start looking for data on where we’ve invested in machines over the past 100 yrs. It takes a minute to grok, but it tells a pretty compelling story.

First we invested in machines to move stuff. Engines. Engines led to automating the manufacturing of stuff that makes other stuff: machinery.

Once we got good at that, we started to invest in thinking machines (computers) to tell us what to make. Engines of information.

Now the bulk of private capex goes purely into investing in ideas, in the form of intellectual property. You can literally see the abstraction and digitization of the US economy in these charts.

Bringing this data up to date, you can see this trend of investing in ideas has swept the entire US economy. Starting in the tech (or what they used to call the “information”) sector in the 80s, the share of IP as a proportion of total tech capex has pretty much doubled across the board. Now one in three investment dollars in the US private sector is going into ideas/content/IP!

Though with substantial difference within each sector. As you would expect, some sectors need ideas more than others. More on this in another ramble.

What does this mean for the broader economy?

What was the economic narrative from the 1950s to the 2000s?

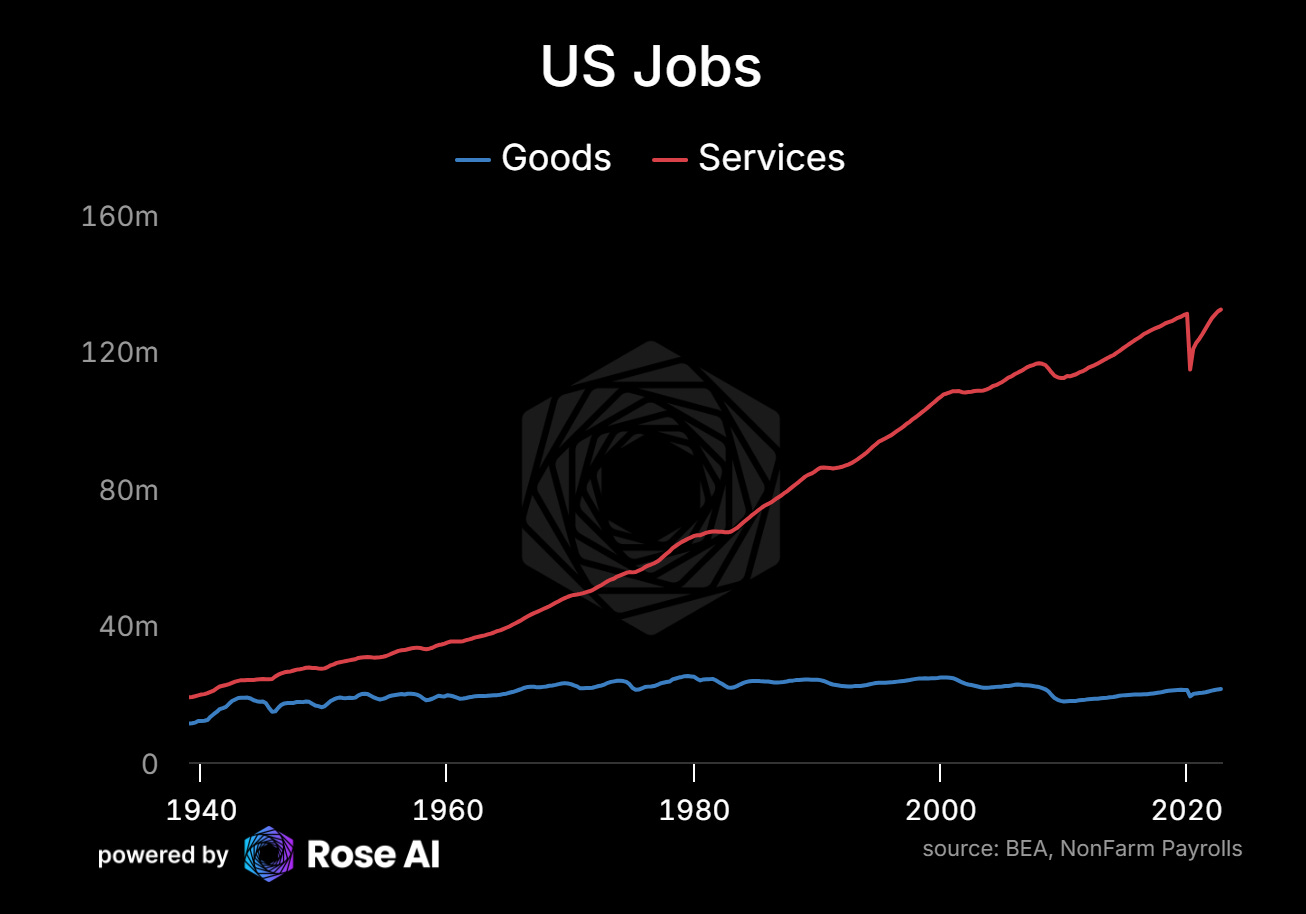

As we became increasingly efficient at producing tangible goods, including energy, a growing proportion of the workforce shifted towards producing intangible assets: the “Service Economy.”

We used to call it the service economy, but we should have called it the paper economy.

Your great-grandfather wished his kids would push paper in a ‘white collar’ job in the big city. Now mothers hope their daughters ship code from home, in a nice California neighborhood, in their sweatpants, making “700TC”.

At least until the robots show up.

This shift towards investing in information offers an intriguing perspective on the 'creator economy.' How else can we define a YouTuber except as someone who generates information for others' consumption? How do we account for their labor in GDP calculations? And how do we measure the productivity of memes?

These sound like crazy questions, but as our economy gets more and more abstract, and less and less physical, we’re going to have to try to answer these questions. A lot of them frameworks familiar to people in…venture and tech. Folks who have been trying to price eyeballs, clicks and attention for long time.

This concludes part two of our series "Where Did All the Farmers Go?" In this installment, we've brought the story up to date, and demonstrated how the concepts of automation and investing in intellectual property have essentially converged in the modern context.

Next time we will use these two pieces as a foundation for a set of speculations. The first about the future of work. The future of work in a world where the marginal cost of intelligence suddenly becomes tied not to the supply of humans, but energy. A future where workers are more directly compensated for their ideas not their labor. The second set of speculations of which physical investments we should expect to see the most demand. No surprise it will be the energy, chips, and pipes that make this idea economy possible.

Until then.

Disclaimers

Charts and graphs included in these materials are intended for educational purposes only and should not function as the sole basis for any investment decision.

The key question is when will the education system catch up