The Arsenal of Autocracy

How We Armed Our Rivals

(Context: I spent a couple of hours with GPT5, Claude and Grok working out the numbers below. Then fed a rough draft of the argument in this post into a model along with FDR’s “Arsenal of Democracy” speech from December 1940 and said “How would FDR say this”? This is what results.)

My friends:

This is not a discussion of trade policy. It is a warning on national survival, because the central purpose of your leaders must be to recognize that we have already entered—not may enter, but have entered—a competition for the preservation of democratic independence and all that such independence means to free peoples everywhere.

Tonight, in the presence of a strategic crisis, my mind goes back to December 29th, 1940, when Franklin Roosevelt warned Americans that their civilization faced mortal danger. He called upon America to become the great arsenal of democracy. Today, we face the inverse reality: we have allowed our adversaries to become the arsenal of autocracy.

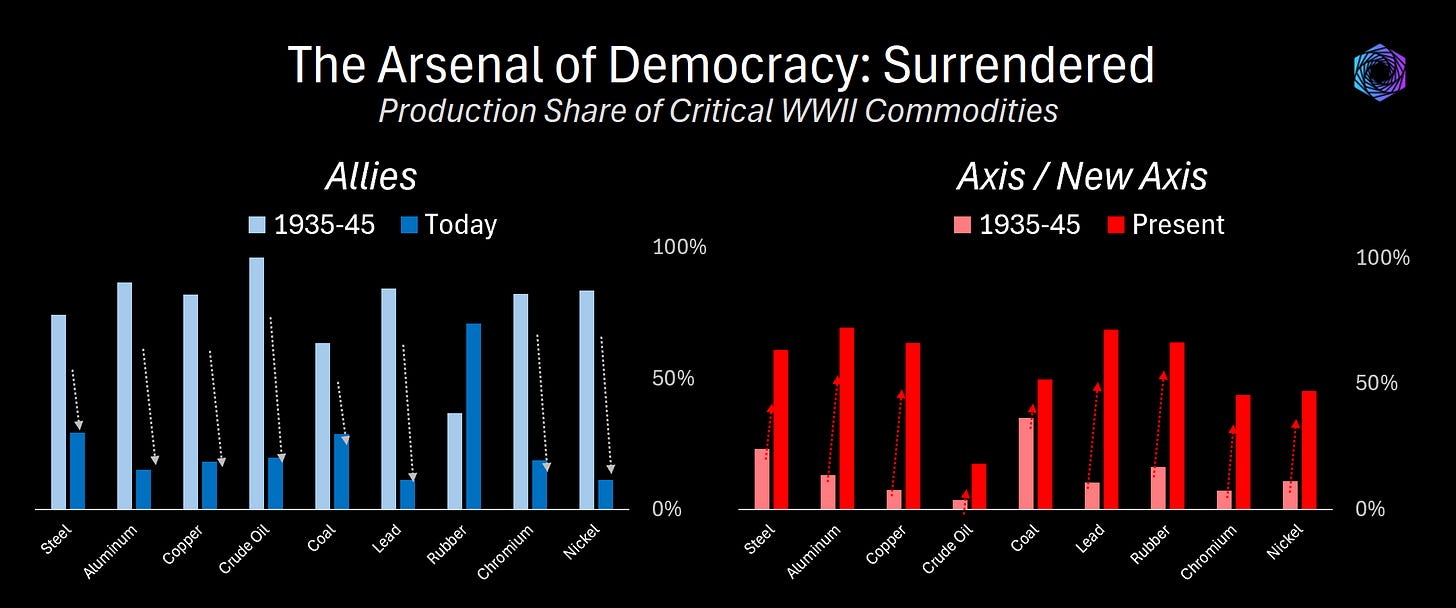

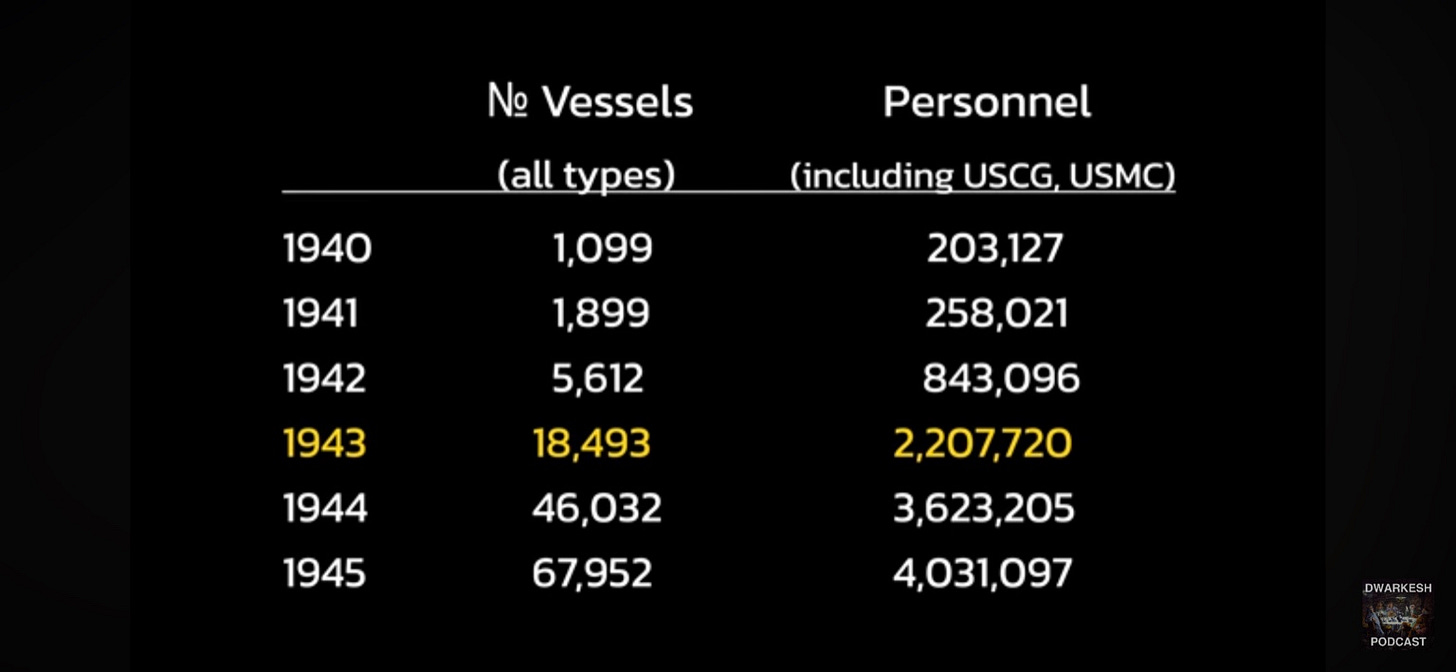

We met the challenge of 1940 with industrial might and collective purpose.

We face this new crisis—this new threat to the security of free nations—having surrendered that might, piece by piece, factory by factory, to those who oppose our values.

Never before since that wartime mobilization has democratic civilization been in such material dependence on its strategic rivals as now.

The Great Reversal

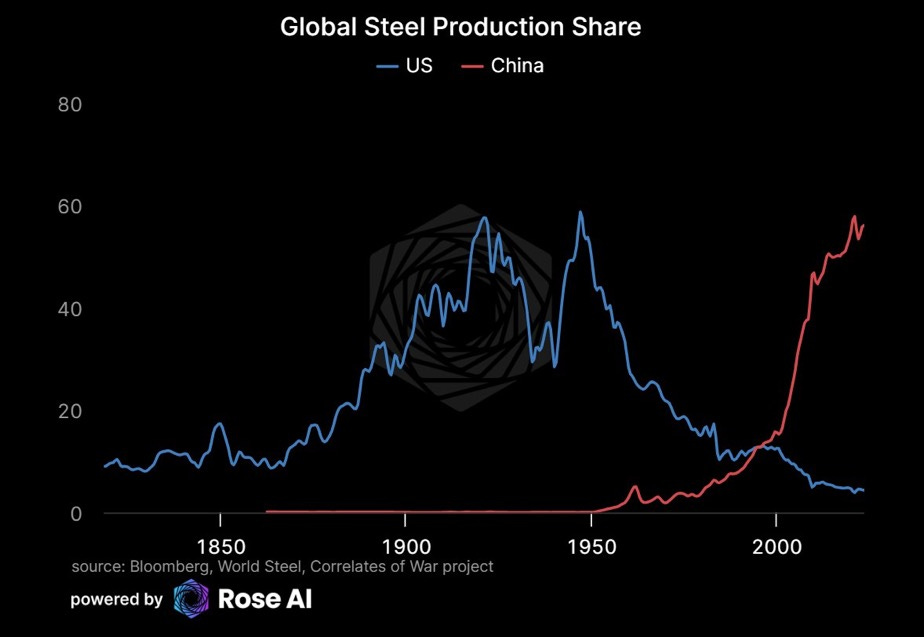

The charts tell a story of civilizational surrender. In 1945, the Allies controlled 85% of global steel production, 80% of aluminum, 90% of copper, and virtually all crude oil outside Axis territory.

Today, those same democratic allies control just 29% of steel, 26% of aluminum, and have ceded dominance in every critical material to a new axis of autocracies.

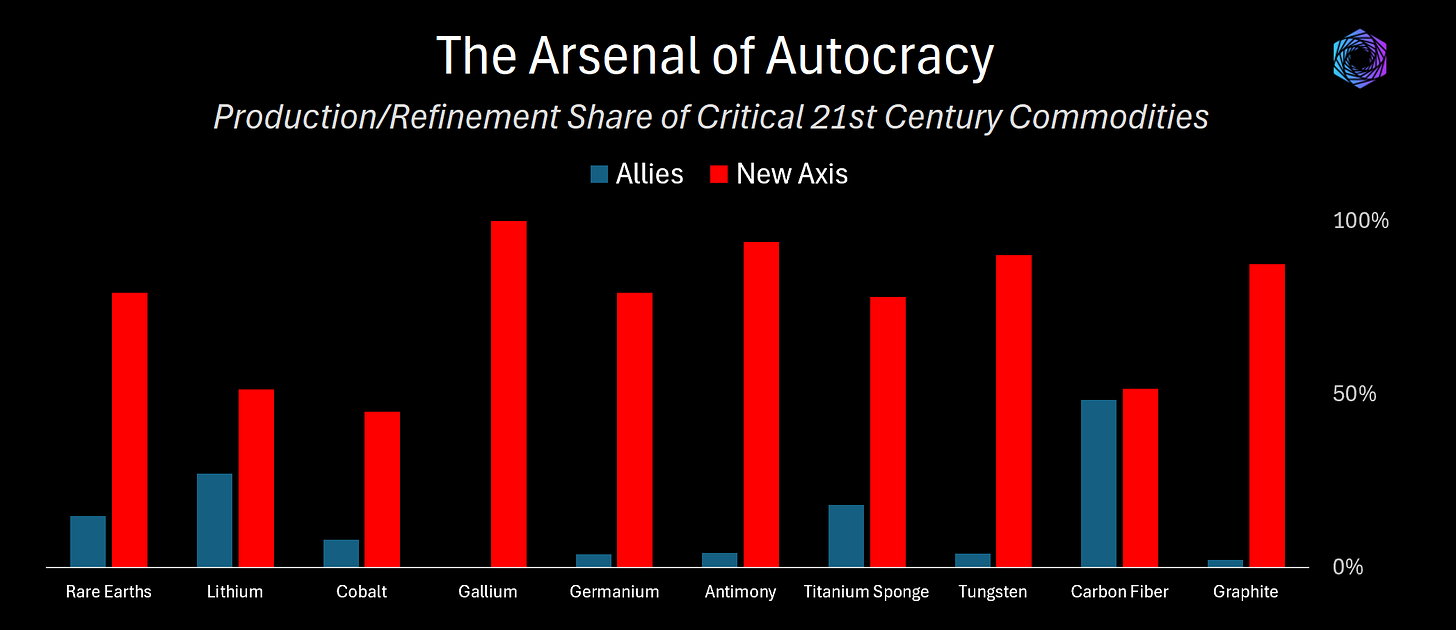

The reversal is even starker in 21st-century materials. China and its authoritarian partners control 99% of gallium, 95% of rare earth processing, 83% of tungsten, and 78% of lithium processing. Every green transition technology, every smart weapon, every semiconductor depends on supply chains that run through Beijing’s hands.

For today, by decisions made in Beijing, three-quarters of our defense systems depend on materials controlled by a nation that views our alliance system as the primary obstacle to its ambitions. When China restricted gallium exports last year, they demonstrated that any company claiming to know their supply chain is like a company saying they’ve never been hacked.

The leaders of China have made clear they intend not only to dominate production in their own country, but to make the entire democratic world dependent on resources they control, and then to use that control as leverage for geopolitical dominance.

The Width of Oceans

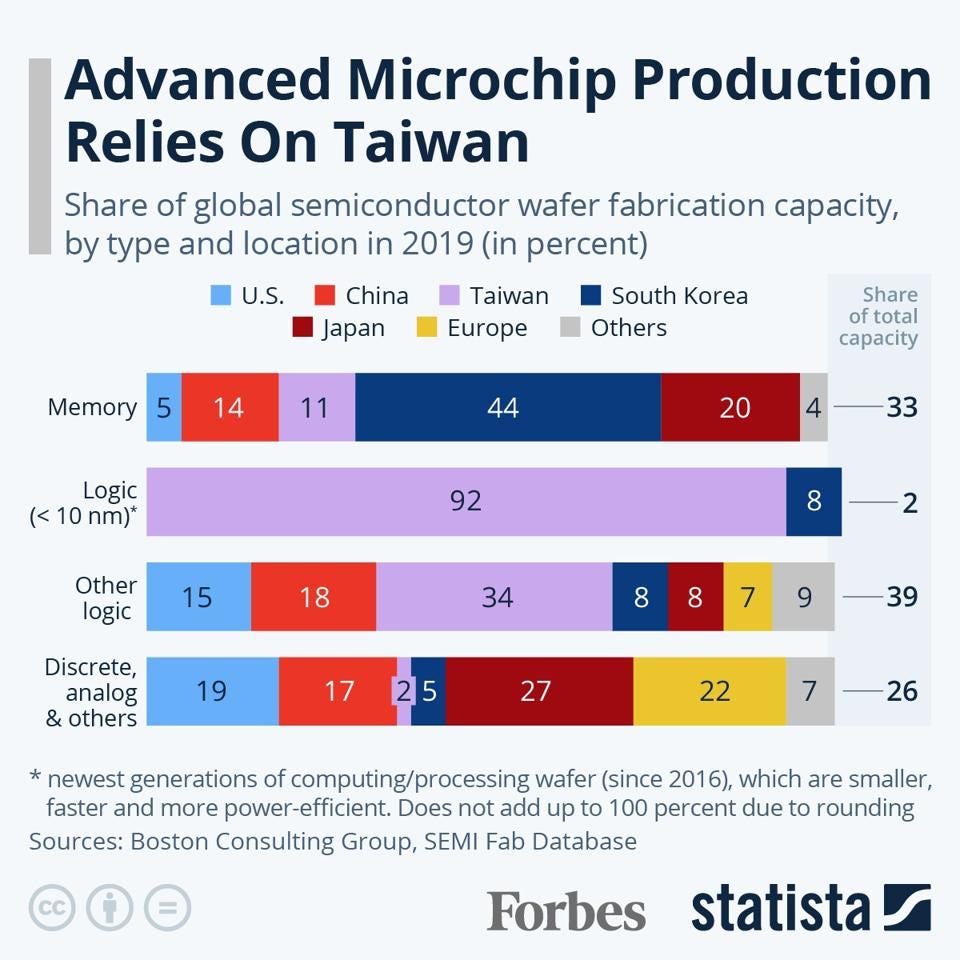

Some of us like to believe that semiconductor production in Taiwan and material processing in China are of no concern to us. But it is a matter of most vital concern that 92% of advanced chips flow through facilities 100 miles from the Chinese coast—closer to Beijing than Cuba is to Miami.

In Roosevelt’s time, the width of oceans protected us. Today, a single earthquake, blockade, or “special military operation” targeting Taiwan would halt production of nearly every advanced electronic system in the democratic world within weeks.

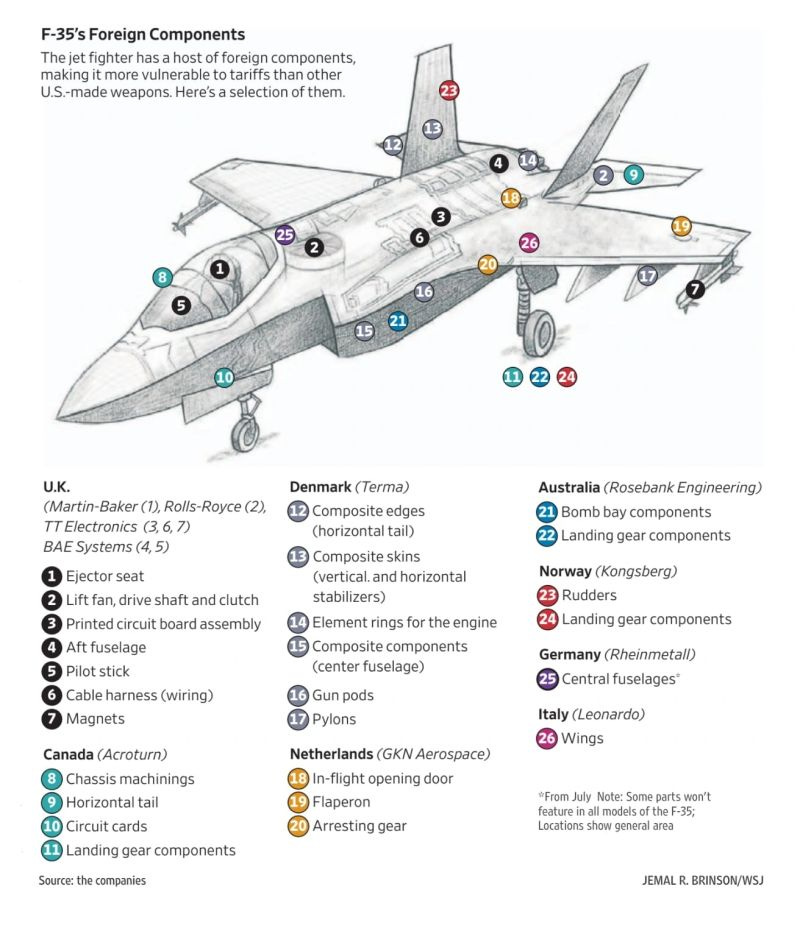

Does anyone seriously believe we can maintain military superiority when every F-35 requires 920 pounds of rare earth elements that China exclusively processes? Does anyone believe we could sustain our economy if the semiconductor flow from Taiwan stopped tomorrow?

If Taiwan falls under Beijing’s control, China will command not just rare earths and critical minerals, but the very neurons of the global economy. It is no exaggeration to say that all of us, in all the democracies, would be living at the mercy of supply chains weaponized for political submission.

The Plain Facts

During the past decades, many people in government and industry told us that global supply chains would make war impossible. That economic integration would guarantee peace. One might summarize their message as: “Please, citizens, don’t frighten us by telling us we’ve traded our security for marginally cheaper products.”

Frankly and definitely there is danger ahead—danger we created ourselves. We cannot escape it by pretending our 4% share of global steel production can match China’s 54%, or that our three Javelins produced daily can match Ukraine’s need for 500.

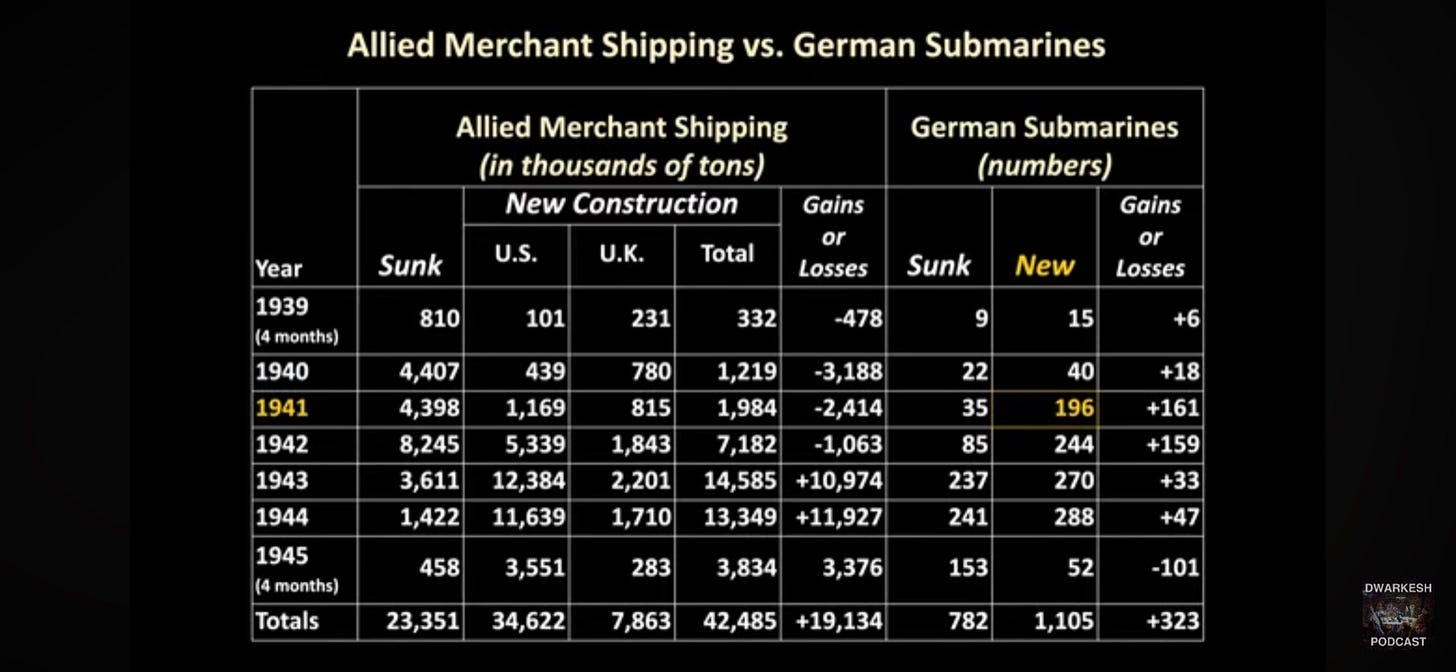

The fate of our industries tells us what it means to live at the mercy of autocratic supply chains. Our shipyards that once launched a Liberty Ship every fourteen days now struggle to maintain four submarines annually. Our steel mills that armed democracy now import the specialty steels our power grid requires.

Germany believed Russian gas integration guaranteed peace—until it didn’t. Japan thought rare earth imports were just commerce—until China embargoed them over a fishing dispute. These trouble-makers have but one purpose: to divide our alliances into competing supplicants, begging for the materials our own weapons require.

New Britains, New Alliances

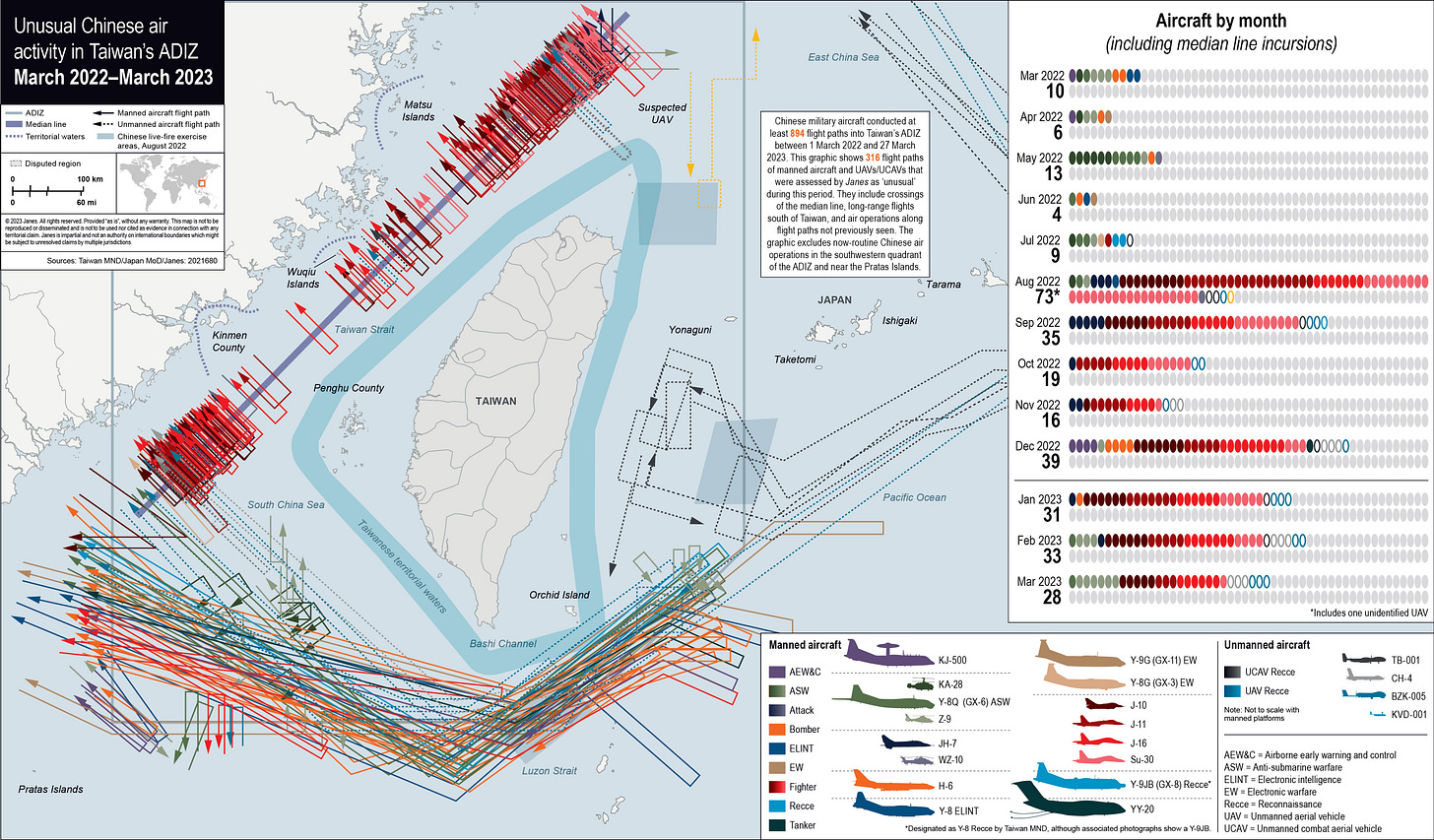

South Korea and Japan today are the spearhead of technological resistance to authoritarian dominance—they are Britain in our current struggle. Korea produces almost a third of the world’s merchant ships, building in a single month what America might construct in a decade. Japan maintains the materials science and machine tool excellence that once defined Detroit and Pittsburgh. Taiwan stands as the singular fortress of semiconductor sovereignty, its survival as critical to democratic technology as Britain’s was to democratic survival in 1940.

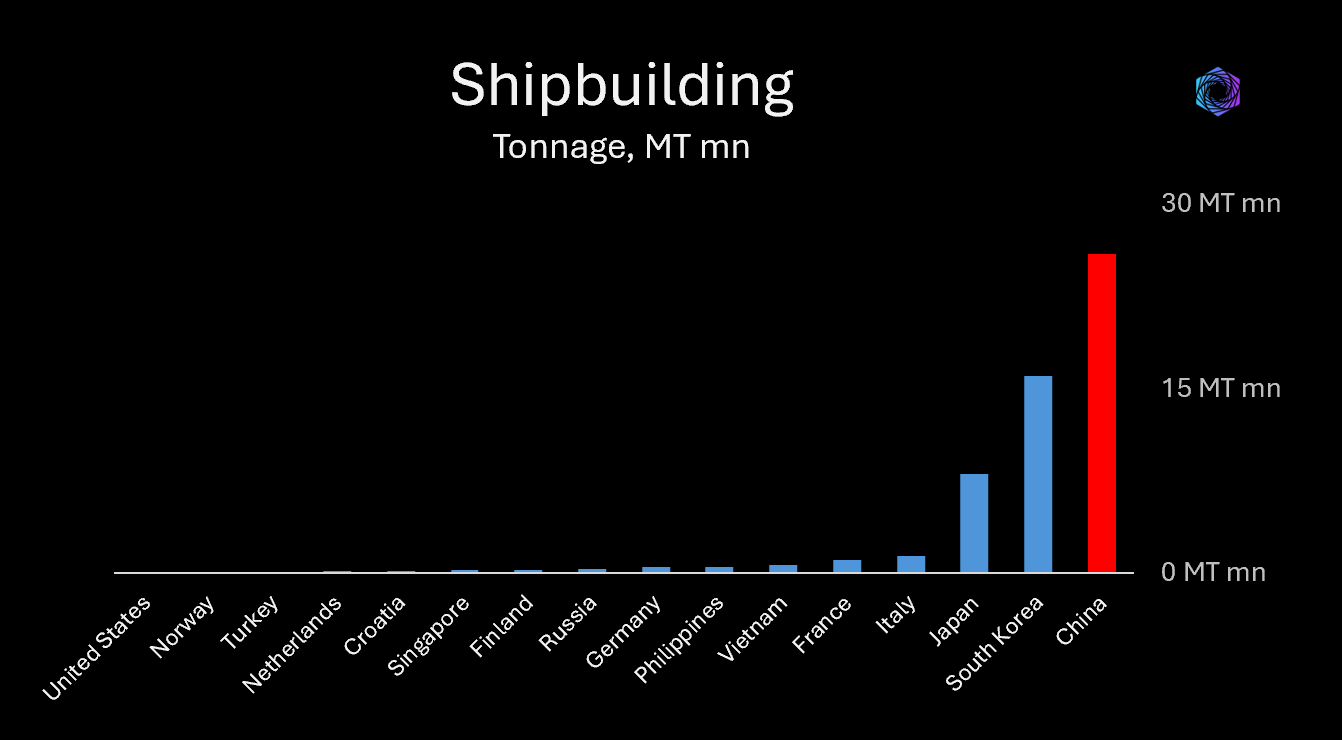

Yet even these allies cannot stand alone. The shipbuilding chart reveals the scale of our challenge: China builds more tonnage in a single year than exists in the entire U.S. merchant fleet. Without Korean and Japanese yards, the democratic world cannot maintain naval parity, cannot ensure commercial logistics, cannot project power across the oceans that once protected us.

The Uncomfortable Friends We Need

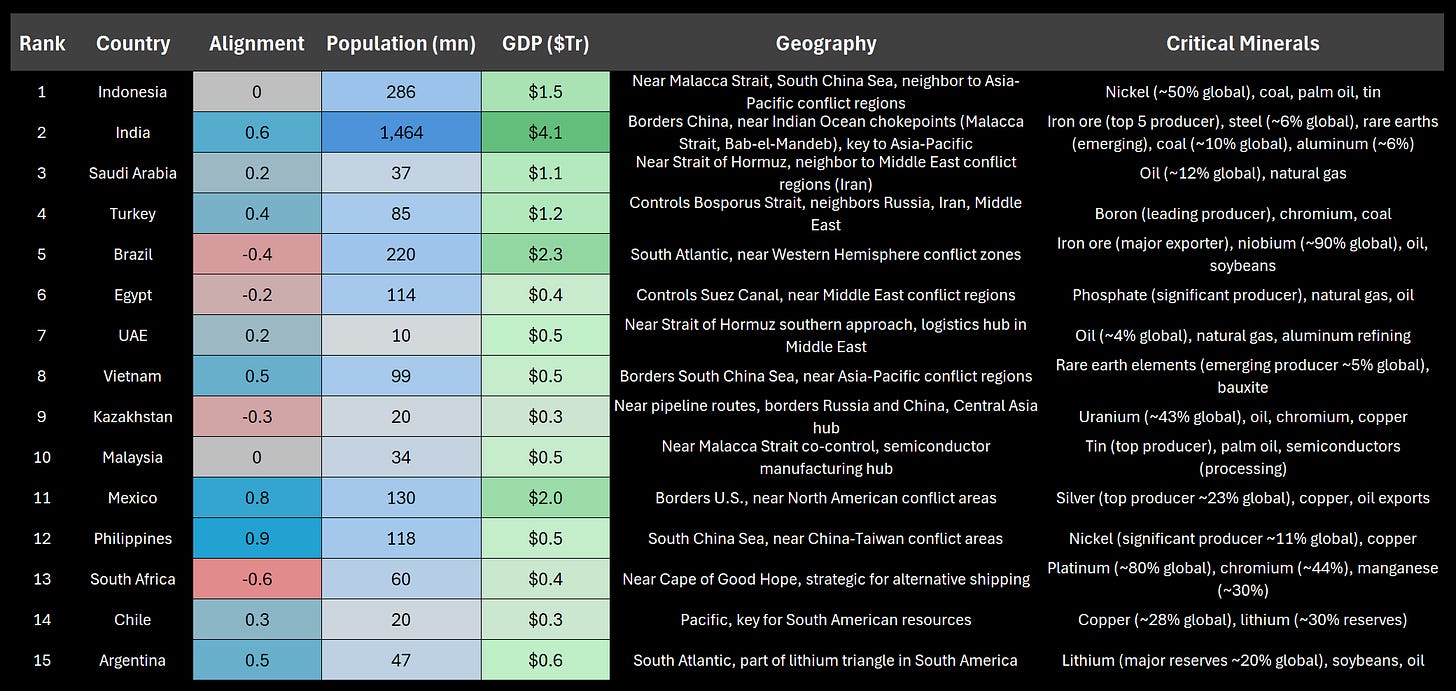

The third chart reveals an uncomfortable truth: securing the materials for democratic survival requires partnerships with nations that don’t fit neatly into our traditional alliance structures. Indonesia controls 50% of global nickel—essential for batteries and stainless steel. Turkey dominates boron production. South Africa holds 80% of platinum reserves. The lithium triangle of Chile and Argentina contains resources that could break Chinese battery dominance.

These nations—neither fully aligned nor opposed, neither democratic nor autocratic—represent the swing states of material power. Their alignment may determine whether democracies can build electric vehicles, whether our satellites can function, whether our supply chains can survive the next crisis.

We must offer these nations something China cannot: genuine partnership rather than debt dependence, technology transfer rather than extraction, shared prosperity rather than neo-colonial arrangements. The battle for critical minerals is also a battle for the allegiance of the global south.

Democracy’s Depleted Arsenal

The British people and their allies today are demonstrating this vulnerability in Ukraine. Our Ukrainian partners fire our entire monthly ammunition production in a single day of intense combat. Our ability to “sustain the fight” isn’t just affected by production—it is defined by it.

Thinking in terms of today and tomorrow, I make the direct statement that there is far less chance of maintaining deterrence if we continue depending on our rivals for critical materials than if we act now to rebuild production among democratic allies and new partners.

There is no demand for abandoning global trade. There is no intention to pursue complete self-sufficiency. But democracy’s survival against authoritarian material dominance is being threatened, and must be secured, by the reindustrialization of democratic nations and the integration of allied supply chains.

The Response Required

This nation must make a great effort to rebuild what we voluntarily surrendered. We must recognize that Korean shipyards are as vital to our security as Norfolk Naval Base, that Japanese materials science is as critical as our national laboratories, that Australian lithium and Indonesian nickel are as strategic as Saudi oil once was.

I am confident that if consumer convenience must yield to strategic necessity, if quarterly earnings must bow to generational security, then such sacrifices will gladly be made for our primary and compelling purpose.

No pessimistic talk about “efficiency” or “comparative advantage” should delay the immediate reconstruction of industries essential to freedom. The possible consequences of failure are much more to be feared than the costs of action.

We must become once again an arsenal of democracy—not alone, but in concert with allies old and new. For us this is an emergency as serious as war itself—because it is the preparation that might prevent war, or the lack of preparation that guarantees defeat.

The Axis powers of our time are not going to abandon their leverage voluntarily. But I base my hope on this fact: free peoples, when awakened to danger, have always outproduced and outinnovated authoritarian systems—when they chose to produce at all.

As Roosevelt said, there will be no “bottlenecks” in our determination—but first, we must acknowledge that we have become the bottleneck. No combination of dictators should be able to hold hostage the materials democracy needs to defend itself.

I have the profound conviction that free nations, working together with pragmatic partners, can break these chains of dependence we forged ourselves. Japan reduced Chinese rare earth dependence from 91% to 58% through determined effort. The CHIPS Act, however insufficient, shows recognition of the crisis. Consider what democracy’s reindustrialization actually requires: MP Materials spent $700 million and seven years to build America’s first rare earth processing facility in Texas, breaking China’s monopoly on neodymium magnets essential for F-35 fighters. TSMC’s Arizona fabs will cost $65 billion and won’t reach full production until 2028—and even then will produce chips two generations behind Taiwan’s output. These facilities cost more, take longer, and produce less than their authoritarian competitors—but they exist, they work, and they prove that security costs more than surrender but less than subjugation.

I call for that allied effort. I call for diplomatic creativity that sees potential partners where we once saw only complexity. I call for it in the name of those who will inherit either freedom or dependence based on our choices today. I call upon our peoples with absolute confidence that our common cause—the cause of production, of tangible capability, of industrial strength—will determine whether democracy or autocracy defines the next century.

The arsenal of autocracy wasn’t stolen from us. We gave it away, one factory at a time, for marginally cheaper phones and slightly higher margins. The question now is whether we possess the wisdom to build new partnerships, the courage to rebuild old capacities, and the will to take back the means of our own defense.

Till next time.

Generally agree.

But would place more emphasis on the upside of latin American partnerships

It’s ok. We’ll beat them with what we do best. Enterprise SaaS.