Irrational Doomers

SB-1047 is a different kind of rat trap

The bulk of this ramble comes from a talk I gave this summer at the less.online conference. Nestled deep in the heart of Berkeley, California the conference was hosted by “rationalists” and open to various hyper-online communities. EA was there, TPOT, even folks from the crypto world interested in prediction markets.

You see, in case you haven't heard, we've solved rationality.

Turns out, from a "rational perspective," the only thing that matters in the world is the impending and inevitable end of humanity via the rise of the machines.

“After all, it’s existential!”

Which you no doubt have heard by now 30 seconds into any conversation with a “doomer”. So I thought it might be interesting to go into the heart of the dragon (and the epicenter of lobbying for the “Kill AI Bill” SB 1047) to co-host a talk with Nathan Young called “Why it’s irrational to be worried about AI doom.”

The argument starts with a steelman.

The Steelman - The Argument for Doom

To lay out the case for the irrationality of obsessing over existential AI doom, we first need to understand it. For this first part, we're going to use a tradition from the rationalist community called 'steelmanning,' which involves presenting the other side's case in the strongest possible way before critiquing it. The goal is to tackle their best arguments, not their worst.

With that in mind, here’s the steelman argument for AI doom:

Compute is scaling exponentially

Intelligence scales with compute

Intelligence = Power

Power is instrumental

Misalignment is inevitable

Look at how we treat animals

We are running out of time

You can think of these as a series of escalating premises, where in order for the conclusion to be reached (“we are running out of time to avoid existential danger → we must stop/pause/retvrn to the forest immediately”), you need to accept each of these premises in turn. Intelligence scales with compute, compute is scaling exponentially. This intelligence will inevitably lead to extremely powerful, extremely misaligned machines, which, given the way we treat animals, means we have very little time before they wake up and decide to eat us for dinner (or turn us into paperclips, or harvest us for our hydrocarbon chains or use us as batteries or whatever). We can synthesize this view into a “probably of doom” or p(doom) which aught be quite high (more on this later).

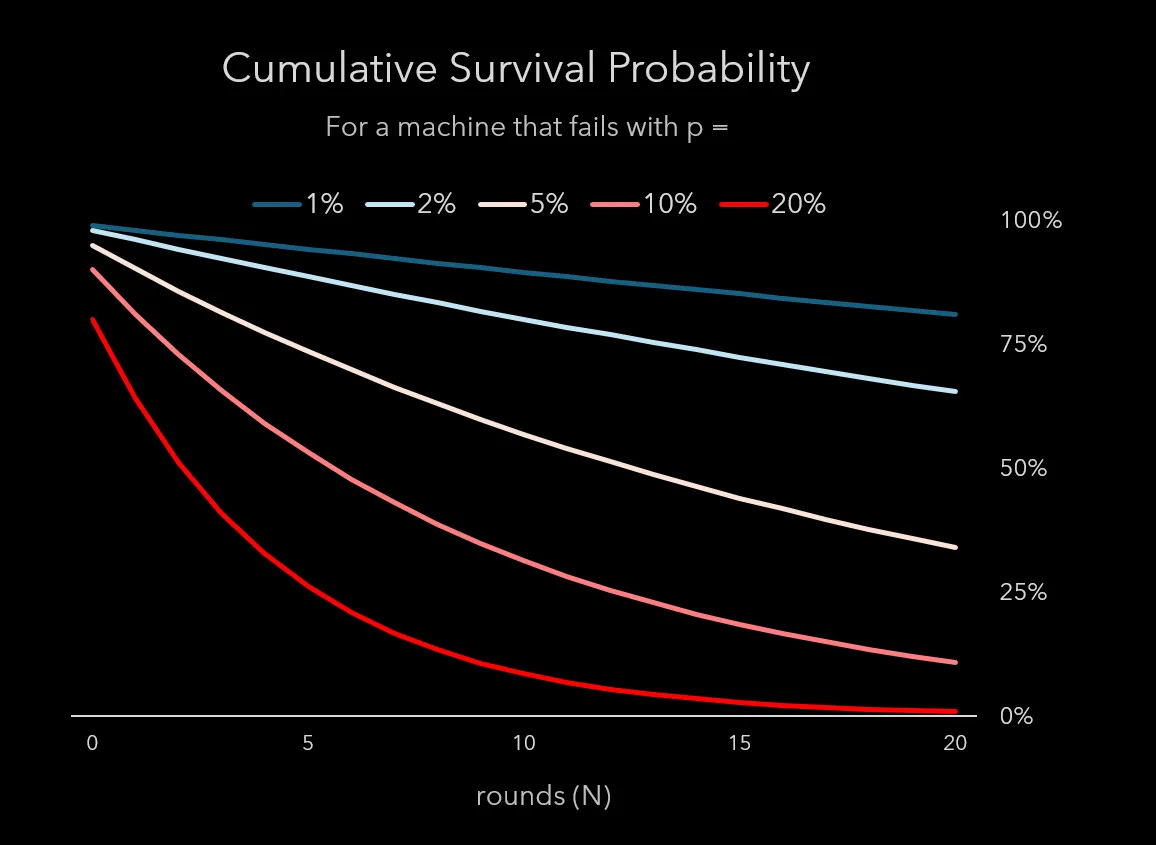

Below going to go into each of these points line by line, I first want to point out that this set of arguments is actually a “chain” of logic. Meaning to believe the final conclusion - that your p(doom) should be high - you need to believe each of the underlying steps. And not just one or two, but all of them. Given the probably that the conclusion is true is just the odds that all of the premises are true, which you can derive by multiplying them (ignoring correlation for a moment), you actually need to be extremely confident in each of these premises in order to end up with a very high expectation of doom. Recall that the odds of p(A and B) = p(A)*p(B), and so if your expectation for any of those seven premises falls below 50%, you cannot have a p(doom) higher than 50%!

Recall from our work on broken machines how quickly the survival probability decreases as you increase the number of steps or reduce your confidence. You can think of the chart below as your p(doom) as you increase the number of steps (or ‘rounds’) and your confidence falls (defined by a low fail probability).

Meaning when you hear someone report high p(doom), they are actually telling you more about the overconfidence by which they build world models than anything useful about it.

Why?

Well, if you were truly rational, you would approach that list of seven criteria not with certainty but with uncertainty. What are the odds that not just one but all seven of those criteria are actually all true (and ‘binding’ as we say in game theory)?

Keep this in mind as we go through both the steelman and the rebuttal. The “doomers” need to convince you that they are right on all seven questions.

What are the odds of that?

Certainty not 99.99999999999%. Because that would mean there’s only a 0.0000001% chance you are wrong. Which, frankly, isn’t very rational.

Compute is scaling exponentially

It does appear that Moore's law, with some assistance, continues to hold.

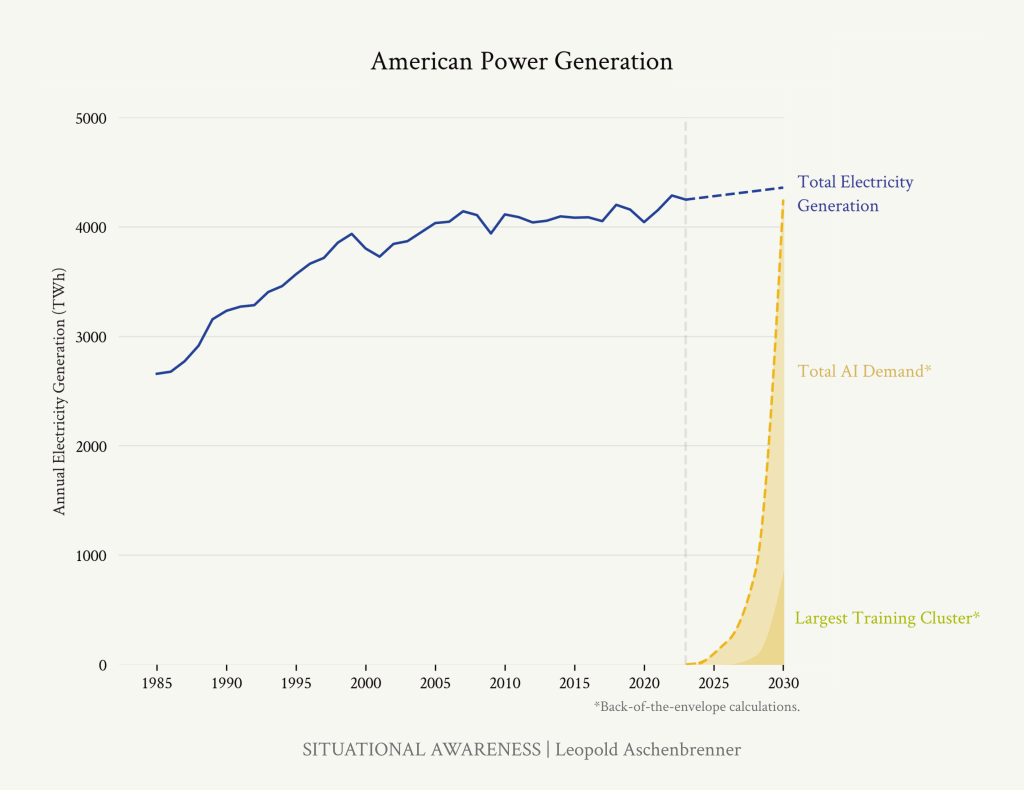

Less well-known is the limitation on this conceptual scaling in compute due to the enormous energy consumption required to power these models. “Double your demand” kind of scale. If you assume models will scale infinitely without considering the cost or availability of power, you're likely starting from an overconfident position. Even satisfying the kind of demand growth outlined in Leopold’s ‘Situational Awareness” article would take twenty years in the US even if the entire house was on fire. The idea of building it in five years is laughable.

Remember this when we come back to the notion of time.

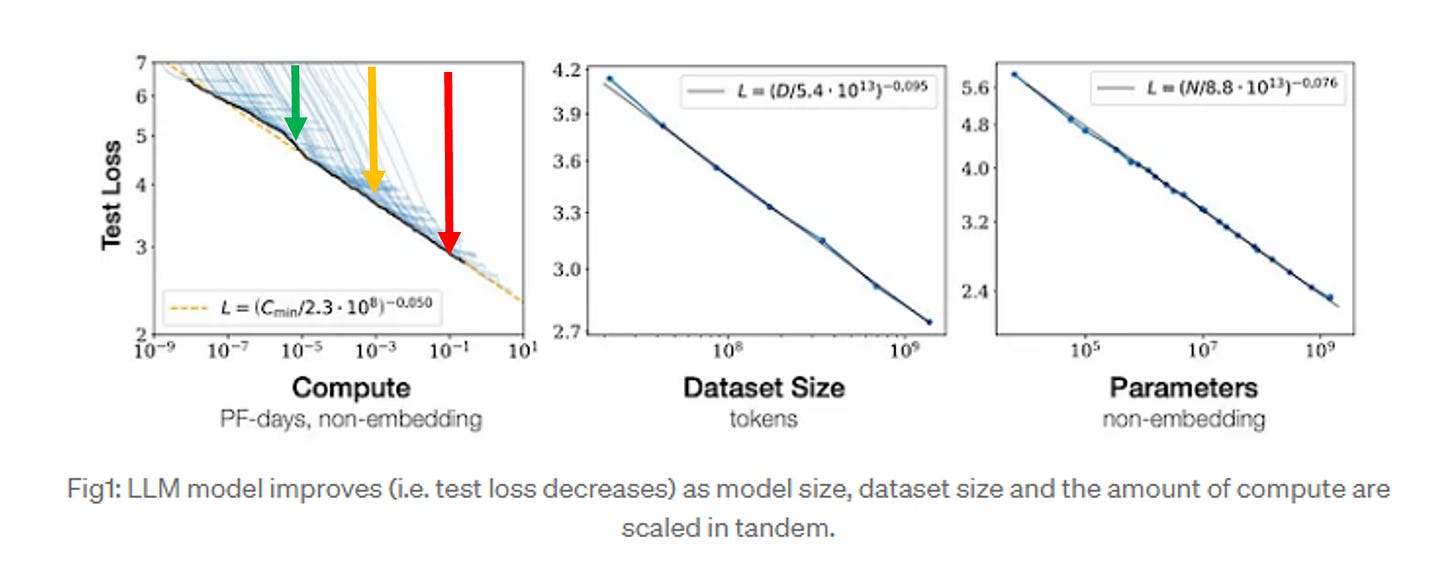

Intelligence scales with compute

One of the core successes from the last two decades of AI research is the insight that throwing ever more compute and data into ever more complex and highly dimensional models actually does result in smarter and smarter robots.

We now live in a world where the bleeding edge intelligence work is defined by a) how much data you can get your hands on, b) how much compute you can throw at it, and c) what novel or innovative techniques you use to combine those two things.

While there are conceptual limits to the degree to which compute can scale given the energy supply required to feed it, this is perhaps the doomers strongest empirical argument, at least in recent history.

We know it’s possible to overfit these models, resulting in something called “model collapse”, but outside of this, the biggest source of uncertainty here is just the fact that we don’t know if the existing transformer-based methods will preserve these scaling past the point of human cognition.

Intelligence = Power

This one is a doozy, and perhaps the place where doomers reveal a worldview deeply disconnected from reality. Apologies to those that have heard me use this question on Twitter, but next time you hear a doomer assume that more intelligence beings are naturally more powerful than less intelligent ones, ask them if they were the most popular kid in high school. Almost definitionally the answer will be no (for pretty much anyone deeply versed in this topic, myself included).

Then ask them why.

The tension here being that everyone knows that the most intelligent person in high school wasn’t the most powerful. Even looking 20 or 40 years in the rear view mirror this would be true (though potentially less so). There’s no amount of pure intelligent scheming that will enable you to automatically ascend a human power hierarchy.

When you look at it on it’s face, this is a ridiculous proposition. Is a Phd student in mathematics more powerful than a grizzly bear? Not if you locked them in a room with the lights off!

The point here being not that intelligence doesn’t help folks find their way to power, or operate as a very potent weapon to do so, but rather there are many types of power. Monetary power. Political power. Cultural power. Inherited power. These forms of power are seldom homogenously distributed and often in conflict. The obsession with the one form of power rationalists have in spades - intelligence - thus makes sense from a cognitive dissonance perspective. We tend to possess a worldview which is supportive of our self-image.

Which is a long way of saying that assuming intelligence equates to power might good for spreading doom and for the self-esteem of the doomers, but it’s actively unhelpful in actually preparing society for a world with intelligent machines.

Why?

Recall our piece on “don’t trust machines”:

There’s an inherent assumption underneath all these arguments that there are problems for which there even exists a correct answer. That intelligence begats power because the robots will just be able to ‘figure it out.’ Which we already know to be false! Not from me but from the greats like Turing, Gödel, Russell, Wolfram etc who came to the same conclusion via different paths.

There are some problems with no correct answers. There are no perfect systems. No infinitely capable machines, just really really really good ones.

By obsessing over and limiting the intelligence of machines, doomers ignore the very real and tangible ways that we already live in a world of broken machines that have a lot of power. Most dramatically in the form of bureaucracy or the innumerable automated systems you encounter in your day to day life.

If you really want to fight the rise of the robots, this is where you should take your stand: not in preventing models from getting more intelligent, but in the way that humans actively and intentionally give them power.

Power is instrumental

This argument is somewhat of a bankshot, but one of my favorites.

The word ‘instrumental’ being a placeholder for the idea borrowed from game theory that more optionality “strictly dominates” less optionality. Strictly dominates just game theory speak for the idea that more options is always better than less options, as long as you keep your old options, because then you get to choose from a broader set of preference maximizing outcomes.

At least from a purely rational, narrowly overconfident, and quasi-scientific perspective. (This is a self-joke because I am a washed-up game theorist.)

Thus, if you ask a robot to go to the store and buy you some milk, it may decide that the easiest way to satisfy that goal is to hack into the Federal Reserve and steal the money for all the milk in the world (along with the other $4tr or so). This would be ‘rational’ from an infinitely powerful robot’s perspective because, all things being equal, having access to infinite money makes it marginally more likely that the robot will be able to meet its goals of making sure you get your milk!

This "instrumental value" of power (or optionality) thus results in machines which are inevitably power seeking. Doomers call this premise "instrumental convergence."

Examining this premise up close, though, reveals some issues with applying it to the real world. The first is that the acquisition of power is costless and instantaneous. The second is that removing the power of others (when in a zero-sum context) does not trigger any strategic replies. The third is that it assumes all games are zero-sum, which we know pretty well from the universe is not the case. The fourth and final objection is that this argument is really just a special case of what's called the 'alignment problem,' which we will get into now.

Misalignment is inevitable

For those of us paying attention, that last step looks a lot like the infamous 'paperclip problem' whereby an all-powerful robot somehow gets it into its head that the best way to meet its goals of making a lot of paperclips is to turn the entire human population into paperclips.

Your intuition might be that this seems like a rather unfortunate (and unlikely) goal, but don't worry, they say, this is just your irrationality.

See (the argument goes), if you consider the space of possible goals/values, and the infinite dimensionality of the potential goals an AI could have, the argument is that it is very, very unlikely that you will be successful in perfectly mapping the values and goals of the machine to what a human would want. (Note the burying of the lede here that we assume we know what we want, which will become pretty important later.)

To me, this argument is the one with the most sleight of hand. See, the problem of 'alignment' has been around a lot longer than the field of AI. Back when writers were trying to build utopia in books and empires, this was an actual practical problem. "If an omniscient and utility-maximizing government is going to make all the production and consumption decisions in the economy anyway, how ought that entity come to that societal maximum?" This has been a problem for economists since Walras was rambling back in 1874 about his 'auctioneer' who ran around the economy adjusting prices by managing local auctions.

Funny enough, a hundred years later Arrow comes out with an "Impossibility Theorem" which answers the question definitively:

Perfect alignment is impossible. There are rational sets of preferences within a group as small as three people which are irreconcilable. It's not just that it's hard, it's impossible.

Anyone with a passing familiarity with politics, the media, or even a big family already knows this intuitively. Sometimes there is no way to make everyone happy.

Meaning even before we get to the problem of whether a machine can perfectly map to a human's preferences, we would need to solve the problem of aligning every human on Earth.

Which is a harder problem than perfectly aligning three people's preferences.

Which, as we just covered, is impossible.

Anyway, the reason we're being pedantic here is to show how 'solving alignment' cannot be the bar for giving machines power. Because a) we know perfect alignment will never be solved, and b) we already have a lot of powerful machines running around, misaligned.

Meaning talking about whether the models can be "perfectly aligned" is a red herring; it distracts from the very real and very present problems of all the broken machines currently running around hurting people. A quick example here is when TurboTax was lobbying the government against making an easy-to-use auto-filing system for income taxes because it channeled people to their crappy product. This, in many cases, not only charged them a fee they didn't need (and couldn't afford) but in some cases gave them the wrong advice.

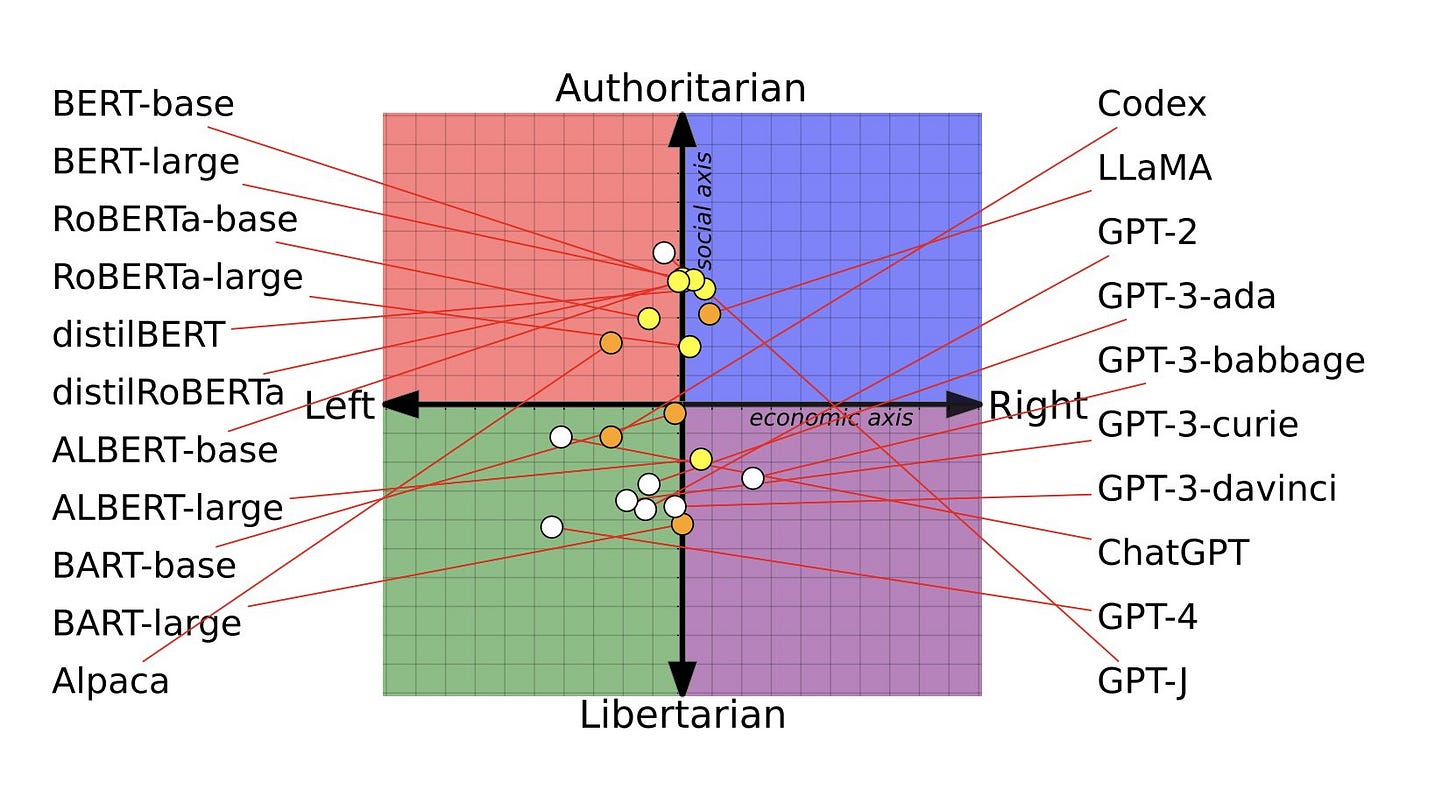

Playing around with the different models directly also corroborates this. Gemini is different from GPT-4, which is different from Claude or Grok. It's immediately obvious that no two models are aligned in exactly the same way. There's a lot of room for aligning them even within the scope of what's considered palatable by the market.

Which calls to mind the way that CNN is different from Fox News or MSNBC. Or the New York Post is different from the New York Times. These institutions have an alignment that is similar in some dimensions and then carefully shaped into some zone within the 'political' dimension such that everyone knows a story from one might have a slightly different tack than one from the other.

Like the newspapers of old, we're going to have to get used to a little misalignment, rather than use its impossibility as justification for a view that the bar is perfect alignment.

The Moral Circle

The argument here is seemingly pretty simple, but like many on the list, actually works against the arguments of many doomers as you play the move out.

The core idea is that as the dominant species on Earth, we humans aren't very nice to the other creatures on Earth. We stick animals in factory farms, consume and pollute their ecosystems, and routinely experiment on them purely for instrumental purposes (knowledge).

Leading a doomer to say, "Would you want an AI to do that to you?"

Now my reply here is a narrow one, and really only applies to a special category of rationalists here: those who claim to be consequentialists while also eating meat and also caring about very long-term outcomes (or "longtermists"). For a lot of moral frameworks, the idea that a machine's moral circle might exclude them is a legitimate worry.

For longtermists, of which I would guess around half of the rationality community ascribes, there is emergent cognitive dissonance between their worldview and their behavior. In order to justify eating a sentient thing, you kind of need to justify the pain and destruction of life involved in your meal. The consequences. If your justification for imposing that harm on an animal originates in their having less moral weight, and that moral weight derives from intelligence, then you are in a pickle.

Because the same moral logic used by you to justify that cheeseburger actually ought to be turned around and pointed at you. Not only does that mean that this worldview justifies placing moral weight in machines with superhuman capacity for sentience, but if you happen to be a longtermist, you might actually have an obligation to bring it into being. But not in the way that Roko's Basilisk compels you to act, out of fear of pain and submission, but rather a positive obligation to participate in the process of creating a life form more intelligent (and hence deserving of more moral weight than you!) A positive obligation to bring good into the world.

There's another objection here originating from Robert Wright's work on the expanding moral circle which says that while we may kind of be jerks to animals at the moment, this is part of a long historical and cultural evolutionary process whereby we have gotten more moral over time. That the scope or circle of folks whom any one individual deems human enough to give moral weight to has radically expanded since the days of hunting and gathering. From family to relatives to tribe to region to nation to species. This moral circle continues to grow and appears correlated to both our intelligence and level of development. Which gives me reason for optimism that an intelligence trained out of a corpus of our own thoughts will come to mirror this energy.

We are running out of time.

Obviously, your perspective on this point depends on your timelines. Personally, I take solace from two things:

First, we actually know that bigger models may be more intelligent, but they also take a lot more time. All that high-dimensional space gives the training process a lot of nooks and crannies to investigate, which means that you need to throw more FLOPs and more time at the problem.

What's interesting here though is the X axis on this scaling chart, which shows various forms of loss against the number of training days it takes. The first thing is that yes, there's a consistent curve you can map these curves to. The second and perhaps more important thing is when the curves reach their minimum loss, and what that implies for training (infinitely) super-intelligent machines.

We have a LOT of time.

Even if we do somehow find a way to get the energy (hi Nuclear!), you are talking about an ~18m cycle at least between the data centers to be built, the data to be gathered, the models to be trained, the loss to be calculated, etc. Even if you had an AI which 'escaped the box,' it would need to find a way to surreptitiously acquire incredibly large swaths of data and compute without alerting anyone, while paying hundreds of billions in infra and energy to run its next generation, and do so for quite some time. Don't believe me? I asked the robot and it also thinks 12-18m. So cut that in half if you want to be pessimistic and then that's just one loop.

Our second objection is that if you are a Bayesian (meaning you think decisions are subject to some amount of 'weighing' options or costs and benefits), then you will know that we have time to "update". Which in this context just means re-evaluate against what we thought was going to happen tomorrow, once we have more information regarding the source of our worry. Regarding AI, we have time to update. A lot of these systems are just going into production and by and large appear totally benign. So now is the time not to yell about existential risk, but to make tangible, tactical, useful predictions and suggestions about what's happening today. Stuff more useful than 'burn all the GPUs' to folks that actually want to make policy. Things that are clear, actionable, and address incoming harms that you see which would lead to bad outcomes in the world. Then rather than chase intelligence, which thus far appears positive, we focus on the places and indicators which actually would go red, if the doomers' worst fears suddenly started realizing. We might want to start with, probabilistically, what prediction markets think is the most likely vector: bio-risk. Which, when you think about it, has a lot more to do with folks slinging pipettes than folks multiplying matrices.

Appendix: Chartbook of historical expectations

Disclaimers

Excellent framework.

Can also add historically how over optimistic smartest people always are on avg. during a build out.

I like the article so far just wanted to challenge the assumption of the growth in electricity demand due to computer chips. I’m not so sure I agree with the chart. Do you know his source for that demand? I think the efficiency gains could offset some or most of the demand.