Inflation, Deflation, Bubble - The Destruction of a Bubble

October 31st, 2020

The Destruction of a Bubble

Many macro folks suggest that by inflating an asset bubble, the Fed runs the risk of manifesting yet another asset bubble collapse. To which we say, yes, but (respectfully) so what?

“To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

– Mark Twain

“To a central banker with a QE playbook, every bankruptcy looks like a reason to print”

-Black Snow Capital

While there are certainly good reasons to be short stocks here (and we are), we believe the biggest risk to the global portfolios is not another short-term liquidity event. One that would inevitably result in more easing and more printing. Rather, we believe the biggest global risk is a shift in the underlying deflationary dynamics upon which all Fed financial crisis policy depends.

Put another way, we’re worried less about the asset bubble, and more about the end of disinflation, which would make the Fed’s promotion of the asset bubble untenable.

This generates a problem with regards to market timing. As PMs, we deal with the problem with an options trader’s mindset. Rather than elaborate on implementation here, we will focus on the fundamental drivers of the cycle.

What will cause the disinflation and what historically has been the primary driver of rising (and volatile) inflation? To answer that, we’ve linked to some of our recent work on the long-term history of inflation. A bit of a chart deck, but worth a scan if you have a minute.

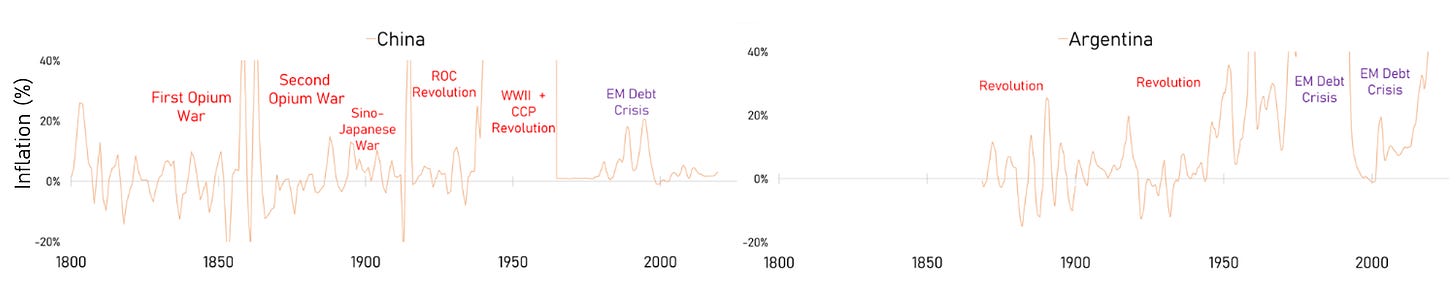

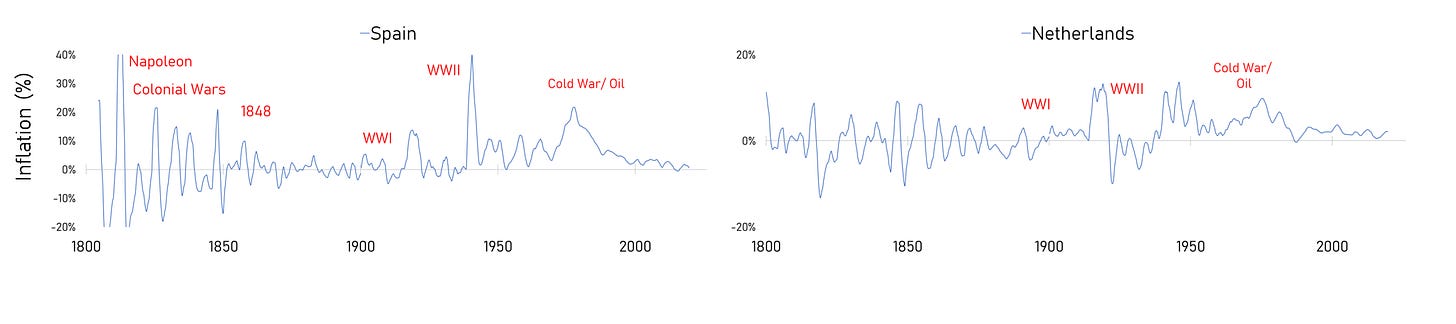

In that deck, we’ve attributed each inflationary event (sustained 10%+ inflation) into one of two categories.: Inflation volatility resulting from financial panics (deleveragings and EM balance of payment crises being the classic example here) vs inflation resulting from internal political conflict or external war..

What you see in the deck, is a lot of charts that look like this:

The pattern here is clear. Financial panics lead to deflation and conflicts lead to inflation.

Occasionally we ease our way out of those panics to get inflation, but generally the largest long-term driver of inflation (especially in the developed world) isn’t policy or bubbles at all, it’s conflict!

Now, one might ask, what type of conflicts matter? Why didn’t wars like Afghanistan or Iraq really register? Looking at history, the type of conflict necessary to register on the scales above usually represents an existential threat to the existing internal or external order.

In this light, the Cold War was a single slow-burn conflict, spread out over 40 years, and constrained in terms of military power by the introduction of the atom bomb. The 50s-80s representing an existential conflict, playing out over a generation through a series of proxy wars and economic tit-for-tat fights.

The first time we saw this was surprising. We spent years learning about traditional business cycle dynamics and never did the role of conflict or war really come up.

The short-term debt cycle and the long-term debt cycle are great frameworks, but if you want to understand inflation in the developed world, it looks like you really, really, need to understand conflict!

This pattern repeats over and over when looking into macro history.

Fight a war, get inflation.

Lose a war…hyperinflation.

Emerging markets have slightly different dynamics. Generally lacking in domestic capital and dependent on the developed world for at least part of their credit system, the role of foreign creditors becomes much more important and determinative. Developed countries, particularly those that issue debt in currencies they can print, seldom go through balance of payments issues of the same nature.

In conclusion, it’s not clear that really anyone is taking this into account, likely due to the brain damage required to clean the data enough to see these patterns. A problem we struggled with so much, we started a data company (Rose Technology) to solve it. So many critical time-series for macroeconomic stats, not just inflation, literally start immediately after the last devastating conflict or hyperinflation.

For example, most Eastern European stats come into being right after the end of the Cold War and the fall of the USSR.

Most modern Western European inflation stats start after WWII, operating from a world of Pax Americana and Bretton–Woods. Go back a little further, and you will find data from the League of Nations stats, immediately after WWI and the end of the gold standard.

Go back further, and you can dig up data on European countries from the Latin Monetary Union, a sort of 19th century test drive for the concept of the Euro.

Go back even further, and you find yourself scraping through French wheat prices from the 1830s or Chinese rice prices from the 1450s, to get a sense of the boom bust cycles of earlier times. Each era, encoding the biases of their time in data, like the way an old tree tracks the weather of its youth in the width of its rings.

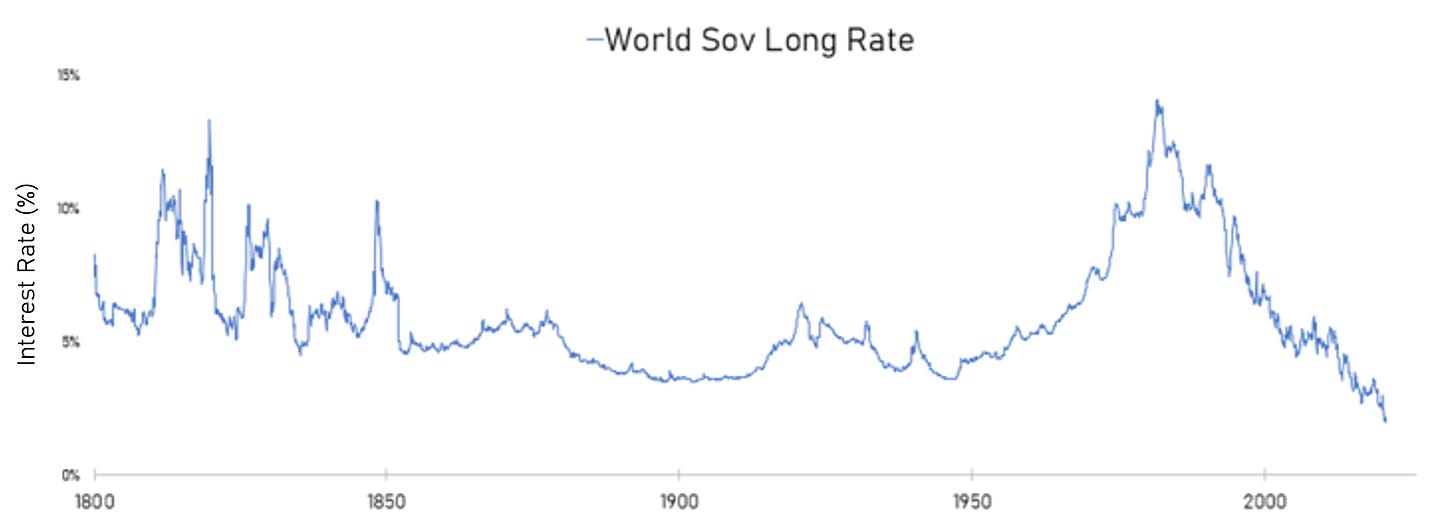

Where does that leave us, particularly as investors in the era of low and negative interest rates?

Cautious for one. Not because we think conflict is especially likely (though on the margin the odds feel like they are increasing everyday), but because it’s just so off the map for most investors.

Like, how many folks realize that the single most determinative force in the long term returns of fixed income isn’t the business cycle, but the conflict cycle? How many folks realize that, prior to WWII, the status quo was conflict?

Looking to today, it feels as though we are in the early days of another cold war, this time with China inheriting the role of the USSR.

A newly industrialized Asian land-power, awoken from a century of slumber, stagnation, and civil war, unified by an ideology fusing nationalism with communism and looking to flex its muscles across Taiwan, the South China Sea and the Indo-China border. China has much less history of external war, and more history of internal conflict (see preceding chart), at times when the emperor loses “the mandate of heaven”. With this backdrop of domestic political vulnerability, China’s recent territorial squabbles take on a more deliberate approach. Foreign conflict acts to distract from domestic problems if the credit bubble really does come crashing down.

However, similar to the last cold war, nuclear weapons give both sides a billion reasons not to engage in direct military conflict. What’s more likely than a grand conflagration between the East and the West is a repeat of the Western strategy of fiscal deficits and containment. Recall it took 40 years to shake out the USSR, and the we had to break the dollar’s peg to gold in the process.

Regardless of who wins the big house next week, expect a bumbling path towards a similar cold-war strategy. The US relying on its reserve currency status to engage in competitive deficit financed spending, investing in a combination of bread and circuses at home, the containment of foreign imperialism abroad, and (hopefully productive) competition to develop the new frontiers of civilization.

Given this wider historical context, all the money China is printing (and the credit bubble that money printing supports), starts to make a lot more sense. Maybe it’s us in the West that are wising up to the game of competition through printing and spending. Maybe both sides are just getting started.

Maybe, just maybe, folks have way too many bonds, and not enough gold in their portfolio.