IDENTIFYING AND MANAGING RISK IN YOUR "LIFE PORTFOLIO"

I don’t think people understand diversification well.

The core concept is simple, understand the risks you face, and don’t put all your puppies in one basket. But looking around, I see quite a few puppies, and not many baskets. This post is about my personal journey towards an appreciation for diversification, gained through reflection on 15 years of mistakes.

. . .

My suspicion is that modern, academic finance is partly to blame here. We have obscured pretty simple, intuitive notions under layers of mathematical complexity to the point where the most important concepts are lost.

You don't need to understand the wacky formulas for calculating covariance matrices and optimal weightings to understand what they understood way back in biblical times.

But divide your investments among many places, for you do not know what risks might lie ahead.

This is a great quote. Apparently the Talmud has a similar notion and recommends that people divide their assets equally between land, their business, and liquid assets. Not bad.

On the other hand, here’s a quote from the topper of the wikipedia article:

If asset prices do not change in perfect synchrony, a diversified portfolio will have less variance than the weighted average variance of its constituent assets, and often less volatility than the least volatile of its constituents.

Huh?

Here's one of the key formulas:

Ugh.

Three thousand years and somehow the introduction of math has completely obscured the point.

The top quote nails it not just because it is written in plain english, but because it highlights something entirely absent from the second quote….diversification is about identifying your risks and correcting for overconfidence.

This post is about my personal journey towards an appreciation for diversification. Told through the lens of the various and many mistakes I have made by not thinking well about the economic and financial exposures I created just in living my life..

. . .

Go North, Young Man

Going to college at McGill (as an American) in the early 2000s was pretty neat. Montreal was a weird and wonderful place, the food was great, and the education was about 1/5th the cost of a comparable school in the states.

Going to college in Canada also taught me my first lesson in the importance of understanding asset-liability hedging.

See, part of the reason college in Canada was so cheap (aside from a set of delightful subsidies from the federal government), was the fact that in the early 2000s, the Canadian Dollar was the weakest it had ever been. This meant that, as an American who was borrowing in dollars to pay for school, everything looked (and felt) pretty cheap!

This changed halfway through my time, when the “Loonie” bottomed and began rapidly appreciating, and with it, the cost of my education. My bill for school went up more than 25% in around two years. Somehow the financial aid office failed to inform me that by attending McGill, I was taking a rather large (for me) position in international currency markets!

. . .

A Massachusetts Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

At McGill, I took an interest in economics and computer science. When I wasn’t working in photo shops or seafood restaurants to pay for books, I worked in a behavioral game theory lab where we ran experiments on humans playing games for real money. It was interesting stuff, testing whether people really cared about fairness and the welfare of others.

Eventually, I somehow conned my way into Oxford, and departed for the motherland to study game theory. Whereas once my foreign educational expenses were cheap, now I was living in a country where the currency was as strong as it had been in 20yrs.

Further, while I was at Oxford, the dollar continued to depreciate, and with it, my unhedged foreign expenses appreciated in value. After two years at Oxford, it was clear to everyone that I am not quite cut out to be an academic. Too much…something. Thus we enter the final leg of the (particular unprofitable) currency trade that was my personal finances.

See, since I was taking out loans to go to grad school, I had acquired assets (and liabilities) in dollars. Every quarter, I converted some of those dollars into pounds to pay for tuition and expenses, locking in the prevailing exchange rate. As the pound rose, I thus had to borrow more dollars to cover the same expenses in pounds.

In the final leg of this trade, I began working in London and earning compensation in pounds. Now I had assets in pounds and liabilities in dollars (my loans). However, rather than transfer all of my savings back into dollars as I earned it, I saved in my British bank account...only to see the value of the pound fall more than 20% during the financial crisis.

To sum up...buy GBP high. Sell low. An auspicious start to a career in global macro.

. . .

Trading Places

What was I doing to earn those pounds? Why, working as a prop trader in London at Lehman Brothers (of course).

There's a lot to go into here, but will save most for a later post. The big learning for me here was that when your institutions collapses, it doesn't really matter what your trading PnL (profit and loss) was. You are still out of a gig.

Honestly, I was one of the lucky ones. All I had to lose was my job and a bit of ego (which was probably helpful at that point anyway). More senior people had been compensated in Lehman stock (which was locked up for years) and thus when Lehman collapsed, a lot of people I knew basically lost their life savings.

To add insult to injury, right before Lehman went under, management transferred a reported $5bn of cash from the London office to the New York office (which was subsequently bought by Barclays). Some of which would have gone to severance packages.

Meaning, essentially, the last act of Lehman New York was to raid the firm-wide piggy bank. How do you hedge against that!

. . .

(Investigating)Your Life

At this point, you get the idea. Many times the biggest economic and financial risks are things that are a) totally outside our control, b) systemic and macro in nature, and c) difficult to hedge.

In spite of these experiences (or maybe because of them), I believe it pays to investigate a broader notion of risk and exposure when thinking through diversification.

Understanding risk is about much more than calculating the correlation and variance of your 401k. It's about thinking deeply about your broader portfolio. Your 'life portfolio,' so to speak.

What assets do you have? What liabilities?

What are your sources of income, what are the drivers of that income?

What are your expenses? What sensitivities do those have?

This even extends to the your implicit assets and liabilities. Your skills, your liabilities? If your job is about to be automated, it might not make sense to get that 95% LTV mortgage…

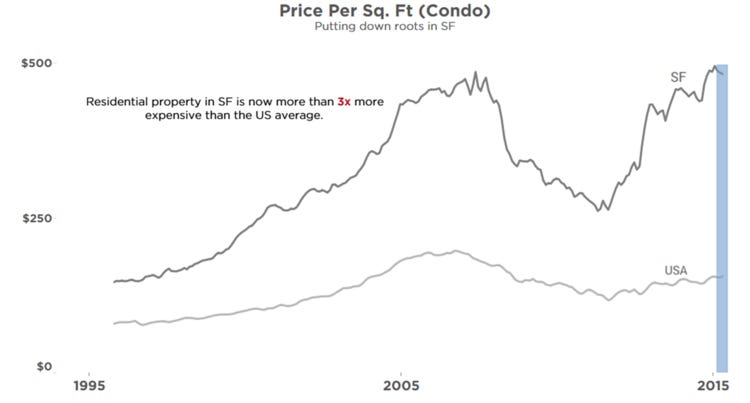

Needless to say, after recently moving back to the Bay Area, we decided to rent.