Contagion Comes to California

The law of unintended consequences meets modern banking regulation

Every financial crisis is the same, but the players are different.

We wrote about this a couple of years ago. Back when we were on the road trying to protect people from the very kind of economic shock we are currently experiencing.

Don’t believe me, take a look. I’ll wait.

The argument came in four parts:

Financial Panics are all essentially always the same.

The Fed’s playbook in response to those panics is ~always the same.

The primary tool of that playbook, lower rates + money printing, was been over-used during 40 years of deflation. Resulting in 10 years of ZIRP (zero-interest rate policy) and a bubble in illiquid, long duration assets like PE, VC, Real Estate and levered duration (bonds). Many of these assets were promoted by famous investors & particularly vulnerable to inflation induced monetary tightening.

The 40 year deflationary wave underpinning that Fed policy - kicked off by globalization, demographics and Volcker - was likely coming to an end. On the horizon was great power conflict, and with it enough inflation to cause a tightening that would destroy the bubble.

Well.

Here we are.

In today’s ramble, we’re going to walk through this argument again, in the context of the Failure of SVB, and talk about the (likely) role that financial contagion will play in the coming week and policymakers likely response function.

All Financial Panics Are The Same

All Anglo (American/British) financial panics are (essentially) the same. I say this with confidence because I made this chart of the last 200 years of them, and came up with a nice alliterative framework called the Five Bs:

Boom ~> Bubble ~> Bankruptcies ~> Bank Failures ~> Bailout

Financial panics generally come about as a result of a Boom in a *good idea*.

Usually some new fangled technological or infrastructure which raises productivity (canals, railroads, telephones, the internet)

Left unattended & in the presence of easy money, a Boom transitions to a Bubble.

Positive returns attracts speculative capital, which pushes up asset prices and pushes down forward expected returns.

Positive returns attract leverage, as we get overconfident about future returns, right at their lowest point.

Monetary tightness causes Bankruptcies in the most over-levered, risky players.

Those bankruptcies cause Bank Failures, usually in frontier corners of the financial system.

For students of the 2010s European financial crisis, we even started calling the PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain) the Periphery.

This kicks off a cycle of contagion, as smaller bank failures put pressure on the larger, more systemically important financial institutions that (in general) provided them liquidity. In Europe, we called Germany, France et al the Core.

Contagion takes over, as (reasonable) worries about the liquidity of the core banking system begin to dominate (reasonable) confidence about it’s solvency. This forced policymakers hands, and we get Bail Outs.

The Fed’s Financial Panic playbook

While the particulars of the bail out vary widely, they generally abide by the following narrative.

Provide liquidity to distressed players by buying good assets at fair prices.

Provide liability guarantees for systemically important institutions (the ‘core’).

Provide support to core banks financial takeover of failing financial institutions.

Lower rates.

Provide liquidity to distressed assets at more than fair prices.

Attempt to segregate ‘the problem’ in a ‘bad bank’ or in government holdcos.

When necessary, print money to recapitalize the banking system.

When necessary, print money to buy government bonds to support counter-cyclical expansionary fiscal policy.

At the moment, we are still at step 1/2, with interest rate curves still are pricing in ~100bps of further tightening this year. In spite of a full hike (25bps) coming out of the curve since Wednesday before the SVB news.

Further, late Sunday as we were writing this, Treasury, FDIC and the Fed released a (slightly) vaguely worded statement implying that depositors would have access to all their money tomorrow morning. There’s a chance we skipped right to the end of our five B framework.

We may have our bailout already.

How Hedged Are The Banks Really?

Noticeably absent from the 2020 piece is really any mention of banks. At the time we were writing to professional investors, and so the role that banks had played in the food fight for duration was a bit of a side story.

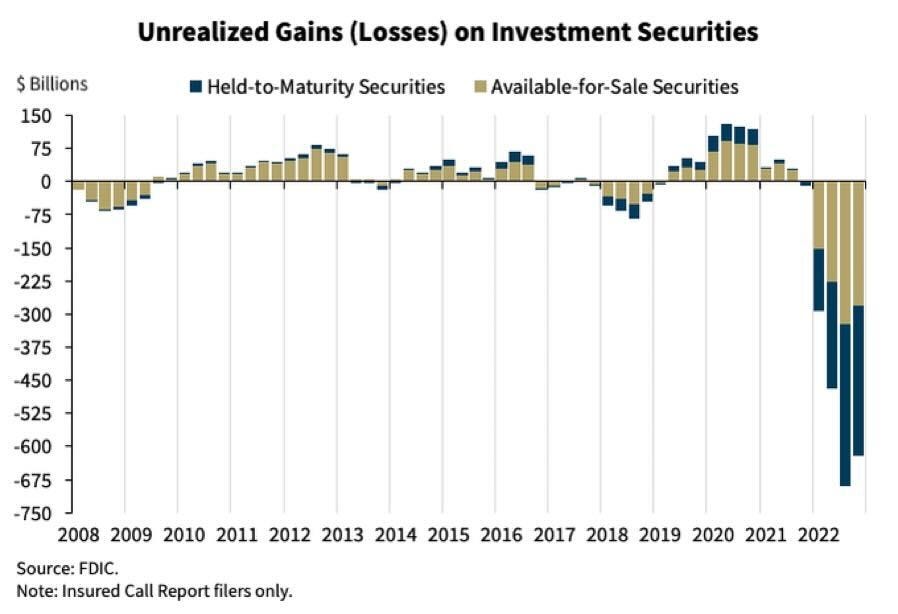

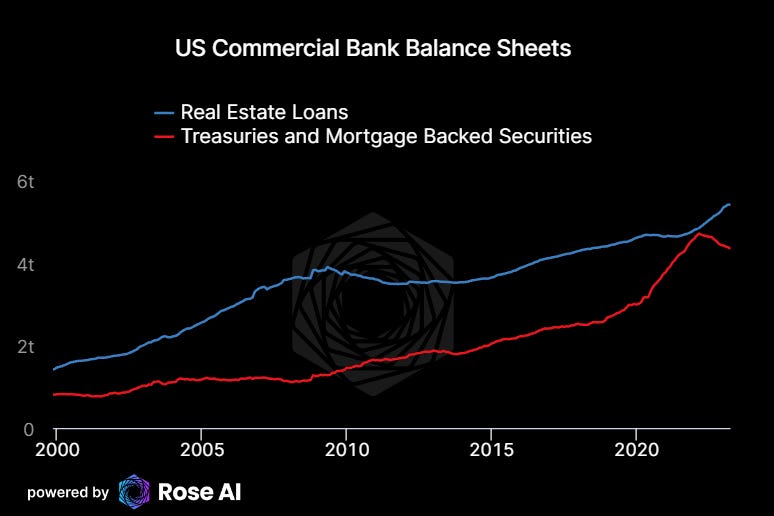

We were wrong. In the two years since we wrote that piece, US commercial banks essentially doubled their exposure to government bonds and “agencies” (mortgage backed securities issues by Fannie, Freddie, and Ginny).

This wouldn’t normally be a problem. After all, it’s the role of the banking system to intermediate your deposit into things like bonds and loans. In the process, they accept credit, interest rate, and liquidity risk as a cost of doing business. Modern banking is essentially the process of then taking these risks and splitting them up into individual elements, each of which can be ‘hedged’ (aka sold to a third party who is looking for that particular risk).

So, what happened to Silicon Valley Bank?

Historically, when we look for problems in the banking system, we look for too much bad credit or too little stable funding. We look for an outsized ratio of loans to deposits, as an indicator that a bank has been particularly risky in their lending.

This was NOT the case in SVB.

Actually, the opposite. SVB, owing to it’s unique place the ‘unicorn economy’ of Bay Area teach, saw a surge in deposits.

In an era of super low interest rates, this was not a problem. Pay 0% on your deposits, and reinvest the proceeds in “safe” assets like government bonds and agency issued mortgage backed securities (MBS).

In fact, if you looked at the value of the bank by most metrics, it was good times!

Problem was, SVB was taking a lot of ‘duration’ risk in doing so.

Aka buying long term assets that were sensitive to the expected path of interest rates.

This strategy was by and large rewarded during COVID, which stopped the Fed’s tightening in it’s tracts and saw the return of ZIRP, and rewarded banks for doubling down on long term debt instruments during an era of historically low rates!

The resulting carnage in the bond market is well documented (by me lol).

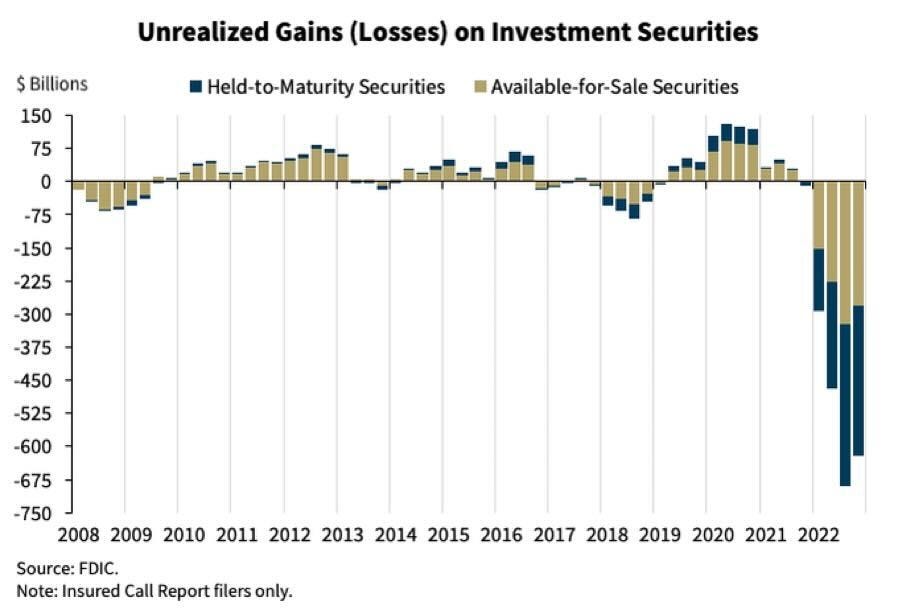

After the rise in rates, SVB was sitting on huge losses, mostly hidden by the fact they were labeled ‘held to maturity’ and hence not subject (necessarily) to mark to market adjustments.

Meaning, if you did the look through their portfolio, the bank was effectively already insolvent going into last week.

The rest of the story has been relatively well covered by the media.

Bank management sells some of those AFS securities at a loss to generate cash, crystalizing losses in the process and allowing the to do the math on the rest of the portfolio.

Stock drops, people start pulling their money.

Alarm bells.

Bank Run.

The Mechanics of Contagion

Well, let’s put ourselves in the role of an unsecured depositor at another regional bank. Someone with $50m in a corporate checking account. Putting aside the potential moral implications of participating in a bank run that could go systemic, it’s a no brainer for them to move deposits to either a systemically important bank with a rock solid balance sheet (JP Morgan) or use the money to buy short term Tbills.

Honestly we wouldn’t be surprised to see lawsuits when this is all said and done by investors looking to punish management teams asleep at the wheel.

Who in their right mind would leave a major proportion of their corporate liquidity in unsecured, traditional deposits?

Turns out quite a few people. Roku for one. $487mn to be exact.

Even financial institutions aren’t immune.

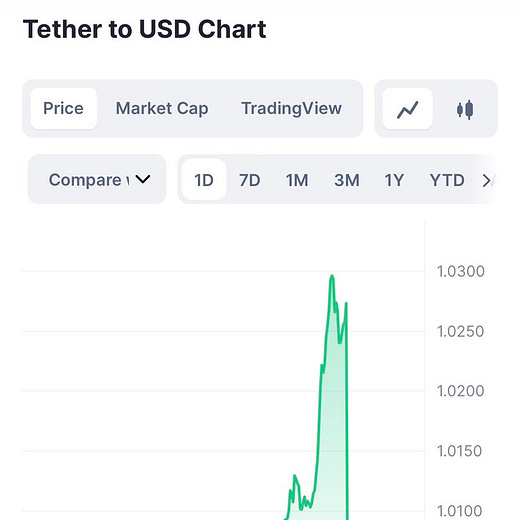

USDC ‘stablecoin’ issuer Circle announced Friday that it also had $3.3bn of the backing their currency in SVB unsecured!

With predictable - and ironic - consequences.

This is how contagion works, and why it’s such a powerfully destructive force in financial systems.

See, money should be BORING.

When depositors have to start thinking about deposits not just as THEIR ASSET, but rather a BANKS LIABILITY, all of a sudden, they have to think about their cash in a pretty uncomfortable way.

“Wait you mean there’s nothing in the cookie jar?” 😬

When your money flips from something easy to something hard, when your money becomes something you need to apply a *discount rate* to, it essentially loses it’s status as money.

If SVB deposits were ‘money good’ there wouldn’t be people buying them from distressed startups at 70c on the dollar.

Where does this leave us? Not in a good place.

ALL CAPS aside, Jason is right. Without further backstop on unsecured deposits, the run will continue.

As we speak the wheels of deleveraging are in motion:

Individuals lining up to take their money out.

Tech investors putting their their portfolios on blast to move their money asap.

Bank analyst all over the world, breaking out their pencils, trying to find out…

Who’s Next?

In the coming days and weeks, you will be overwhelmed with a deluge of analysis. People hunting for too much duration, too much leverage, and not enough liquidity.

This was the kind of work I used to do as a speculator.

First as a Lehman prop trader shorting banks during the financial crisis (lol).

Then, as an investor on the team covering the European sovereign debt crisis in the mid 2010s.

Finally, as a start up hedge fund in 2016, trying to hedge the bubble.

In 2008, that analysis took the form of looking for toxic real estate exposure.

In 2012, we looked for excessive exposure to sovereigns on the brink of default.

In 2016, we identified the Chinese banking system as biggest red, owing to it’s exposure to real estate companies like Evergrande.

This time, it’s not credit that’s the worry. Nobody (yet) is worried about defaults on these portfolios.

Rather, the question is duration.

How many banks gorged themselves on long duration assets and simply…didn’t hedge?

Which is not an easy question to answer. Out of the $4.4Tr of securities on US commercial bank balances, it’s not that easy to track how much in total is hedged, let alone get good bank-by-bank data.

Looking at CFTC data would imply that ‘banks’ have hedged about $1.7tr of this $4.4 (taking matched duration issues out of the equation for a second).

Thing is when you look at the actual underlying data you see that the $1.7tr of bank hedge exposure was offset by a corresponding $1.7tr of *long* exposure held by ‘swaps dealers.’

Which, kind of makes sense when you think of it. Every derivative short needs a long, and turns out it’s the ‘swaps dealers’ that supplied this hedge.

For a bank like Silicon Valley Bank to effectively hedge their treasury/agency portfolio, they need to sell bond duration to people that want it via ‘receiver interest rate swaps.’ Aka contracts that make money when interest rates go up (which replicates the PnL of being short a corresponding portfolio of bonds).

Problem is, who are the swaps dealers?

Also the banks!

Usually, the bigger, systemically important money center banks like JP, Goldman, Morgan Stanley, and Bank of America - Merrill Lynch.

Leaving us, and the market, a bit confused where the risk really is.

It’s entirely possible that swaps dealers are just intermediating Asian bond demand. Relative to Japanese bonds, US bonds look like a great deal!

Even if you assume that ALL of that $1.7tr of swaps dealer long duration exposure is sucked up by Asian financial institutions, you are still left with some pretty chunky losses.

Taking $1.7tr out of $4.4 leaves you around 2/3rds unhedged.

Potentially $500bn+ of losses.

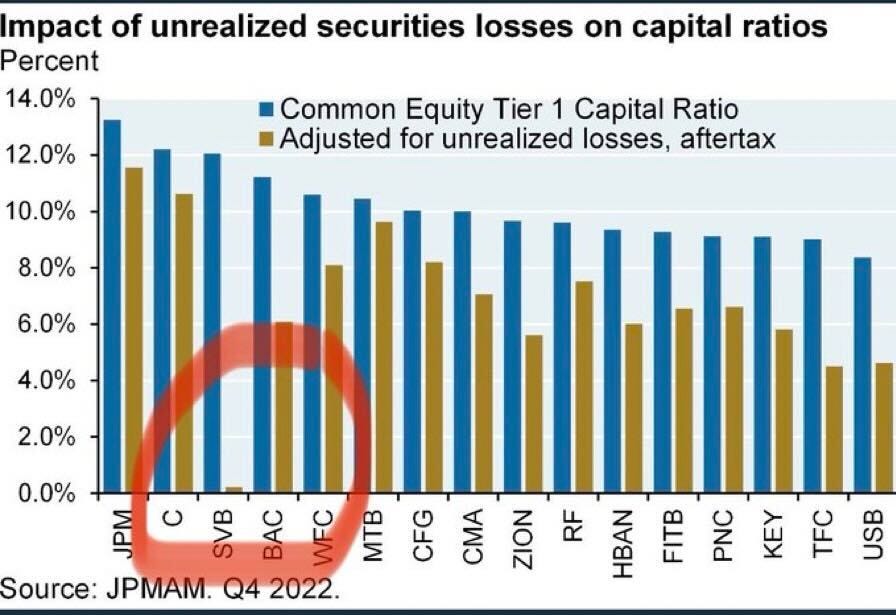

One way to measure the overall risk of the US banking system given these losses is to look at leverage and how well capitalized they are. Looking at data on listed companies reveals around $1.5 trillion of publicly traded bank equity, and about $2tr of book equity (assets - liabilities) across the total US commercial banking system.

Meaning $500bn of losses would represent a hit to bank capital of around 1/3 to 1/4 of their total equity. Regulators prefer to use “Common Tier 1 Equity” (TCE) capital as a representation of loss-absorbing capacity in a bank, which includes other funding instruments, and that $500bn number is likely an over-estimate. We will see in the coming days.

By some measures, US banks are coming into this potential crisis in a strong position.

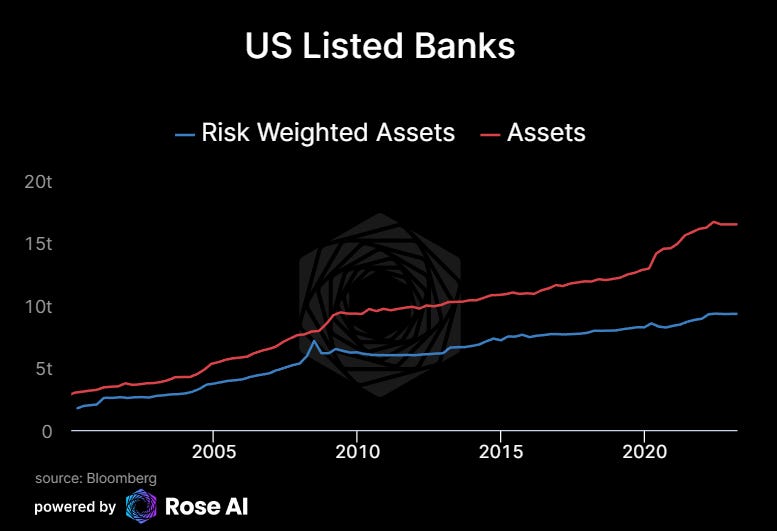

However, focusing on “Risk Weighted Assets” (RWAs) may be burying the lede.

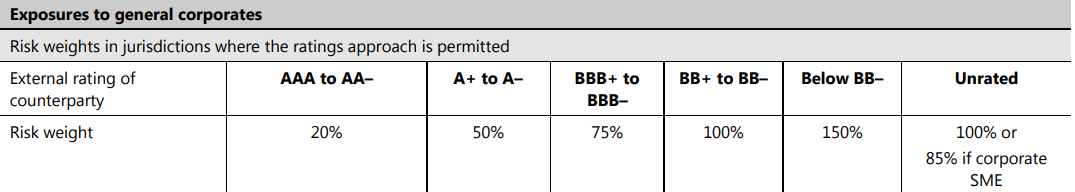

In the wake of the global financial crisis, banking regulators pushed out a new regulatory framework called “Basel III.”

If Generals always fight the last war, then Regulators always fight the last crisis.

Resultingly, Basel III put in place ‘risk weights’ designed to punish many of the complex, esoteric and bespoke derivatives that led to chaos in 2008.

Some of these were a good idea, like weighting exposures to banks, real estate, and corporate bonds according to riskiness.

Perhaps non-surprisingly, when asked to put risk weights on the debt of the very sovereign governments approving Basel III, regulators were a bit more lenient.

On average, bank’s risk weight for central government exposures…is currently around 3% (2016)

What does that mean in practice?

Well, it means that relative to mortgages, bonds, and other forms of credit, the cost of carrying government bonds (from a regulatory perspective) is effectively ZERO.

As you would expect, the American banking system responded to these incentives, and spent the last 10 years gobbling down US Treasury debt. In the process opening up a $7tr gap between balance sheet assets and RWAs.

Meaning, when you compare the loss absorbing capacity in the banking system (as proxied by the equity market capitalization of the listed banking system) to it’s total assets, rather than RWAs, the system as a whole is more levered than before the 2008 or COVID crises.

Where do we go from here?

If it’s not obvious from the tone of this piece, we think the problems unveiled by the failure of SVB are more entrenched and systemic than many analysts assume.

We don’t currently know how many banks are mis-hedged.

We don’t currently now how big the losses caused by Fed policy are.

We don’t know what will happen to SVB tomorrow.

We don’t know what will happen to the unsecured deposits of other regional banks (though they look to be running…)

With all that we don’t know, there are a handful of immediate policy recommendations (based, as you might expect, on the above framework).

First, and most obvious, stem the contagion by raising the FDIC ceiling. It seems Yellen and co decided to take a shortcut here late Sunday by guaranteeing SVB’s deposits.

Second, accelerate the orderly wind-down of SVB and any other bank found too far over it’s skis.

Third, push banks and brokers alike to provide greater transparency and accountability on their duration risk, by reporting their actual net swap positions.

Fourth, make the and having smaller, regional banks undergo the same stress tests that Globally Systemically Important Banks.

Fifth, make the Fed stress test actually stress against monetary tightening. Interestingly enough, the actual Fed stress test only applied a roughly 100bps widening in the credit spreads of the Agency mortgages.

Which seems a bit *light* given we’ve seen a ~400bp rise in mortgage yields in the last 12 months since Powell started tightening.

In the meantime, we look forward to the open of business tomorrow, with hope that the last minute bailout of SVBs depositors will be enough to turn the tide.

Disclaimers