Against Entropy

A Philosophy for the Living

I just left the All In Summit. Towards the end of the conference, Elon Musk made a surprise appearance over Zoom and spoke about the usual topics: Tesla's new car, his Optimus Robot, the Colossus data center, Mars. Say what you want about the man, but he's given proof to the idea that no, you don't have to focus on small things to exclusion of all else to be effective. On the contrary, there's a clear line through his work where the individual projects and line items synthesize across domains and technologies—where the work on AI informs the self-driving cars, where the experience in the factory building the Tesla and the failures with Starship make him uniquely positioned to pontificate on the challenges of building human-scale robots.

Anyway, the point of this post isn't to stan Elon. You already love him or hate him, you don't need my take.

No, the point of this post is to take ahold of something that came up at the very end, something that was actually a theme throughout the conference: the notion that, for all intents and purposes, the West appears to be in the process of committing suicide.

Whether the cause is the death of western religion and the individualism it created, or the guilt from centuries of racism, colonialism and patriarchy. Whether the evidence is declining birth rates, the government-sponsored suicides in Canada, or the cultural death we see in Europe. Whether you think it's a tragedy or a blessing, it seems pretty clear that there's something about liberalism—the classical kind—which is currently in a funk.

The reason I bring up Elon is towards the very end of his talk, while they were speaking past religion, he raised the idea that nature abhors a vacuum and that we need some new philosophy in its place. That it's actually pretty logical that if you take away religion, something else will fill its place. Be it environmentalism which tells us having children is a moral sin, or AI Doomerism which tells us that the act of creation brings upon existential risk, the woke mind virus or its horseshoe cousin authoritarian fascism.

It certainly feels like the world is changing, that things are coming to a head, that the zoomers are onto something when they look at the contrast between the world the boomers inherited and the unaffordable, rigid, uncertain world of endless scrolling and social media enabled FOMO they are destined for. As a game theorist would say, we're in a stochastically unstable equilibrium.

So we begin with a disclaimer: this piece isn't intended to be an endorsement of ANY of these religions, and not really a critique either. Rather, it's intended to be a very personal presentation of my philosophy, a synthesis of a middle-aged life's worth of math, ideas, and experiences. An answer to a very specific question.

Before we get to that question though, we have to go back a bit. Do a little personal history, so you can understand where this all is coming from and why I might care. If this is all too abstract and philosophical for you, and you read this as an investor newsletter, just go read the pieces on gold and silver. Those ideas seem to be working well, and if you understand what follows, you will understand why those trades are still in the early innings.

A Philosophy of Nothing

In the beginning, I was a precocious atheist. I grew up in poverty and chaos. Born of a genius bipolar mother who went to Harvard (Radcliffe at the time) to be a writer, and a genius chaotic father who went to Stanford to be an architect. Both square pegs forced into round holes. Fiercely intelligent, born to good American stock, yet unable to find their way in a world of institutions. "Fallen angels" as we might say in investing.

My mother and father were separated and estranged, owing to his schizophrenia and the resulting abusive tendencies. We lived in the projects, nestled in a very nice town outside of Boston called Brookline. The kind with inner city busing but more PhDs amongst the parents than people on the bread line. Kind of the ideal American melting pot.

All this context to provide a bit of background on why I grew up without religion. My mother, being a good boomer hippy raised Scots-Irish Catholic, baptized me Episcopalian because 'she didn't like all the rules and guilt.' My town was rather Jewish, and whether intentional or not I got a bit of the latent cultural anxiety that comes with it. Which is all to say, growing up, I didn't really see a need for religion. As a child, our life was pretty chaotic, as my mother bounced between jobs below her station and government support, and going to Church just to hear some guy in a cloak lecture me about all this superstructure just didn't map to my real world experience. It wasn't like a big part of my identity, and I didn't bemoan others their religion, it was just absent.

This all kind of changed when I was 10. My mother, suffering from yet another job crash-out (and likely a relapse into booze and what I only later internalized was heroin), was first institutionalized, and then de-institutionalized from a mental health clinic. De-institutionalized not so much owing to her improvement, but rather the insurance running out.

Two weeks later, she was dead by her own hand, and I was effectively an orphan.

Now this is the part of the story where you can have one of two reactions. This is the fork in the road of my life, that leads to the topic of this post and my personal life philosophy. The choice that, more or less, led me here.

Suicide is one of those awful terrible things. Not just because of what it says about those that left, but the questions and challenges it leaves those of us who remain.

As a ten-year-old orphan, with very little material scaffolding, and even less intellectual/spiritual scaffolding, my mother's death called into question everything.

Previous to her departure, I had tried to contextualize my position as positive. Something to learn from. The multicultural environs of my station gave me somewhat of a nascent chip on my shoulder. I promised my mother I wouldn't drink, and that I would try to take our experience on the outside of what I later called 'the machine' of American capitalism, and try to turn it into something good. Take that experience, and you know, make a difference, not just with the gifts she had given me, but the perspective of how easy it was to fall, how precarious and uncertain it felt to be on the outside, looking in on the kitchens full of food and the ski trips and the two-car garages.

I'm not sure there was like a moment after she died I decided to make this my entire life perspective, but more or less that's what I did.

Later in life, coming into contact with ideas like stoicism, Buddhism, existentialism, and depression, I started seeing the interconnected nature of these questions. Maybe in a way that my mother's death put into relief.

See, in a world without God, or a higher power, it's not only natural but kind of necessary, to ask yourself 'what is the point?'

To some, suicide is kind of an answer to this question. "There is no point, life is suffering, so why not opt out?"

An idea echoed in the refrain "why would I bring a child into this world?"

To me, the problem with this kind of thinking isn't that it's pessimistic (even though it is), it's actually that it's wrong. Mathematically.

The Mathematical Case for Meaning

Which is the part where we're going to have to take a bit of a left turn, do a little detour into a couple of my favorite topics, merging math, game theory, and a bit of sci-fi masquerading as pop physics.

We'll start with a couple of precepts. Axioms, that, once justified, actually add up to what is a very simple, cohesive framework not just of optimism but meaning. At least for me, at least for the past thirty or so years.

The Fermi Paradox is real

The Anthropic Principle is true

Entropy exists

Natural Selection is binding (and operates at the highest levels)

The Non-Zero Arc of History

Now this is a bit of a mouthful, and hopefully these won't all be foreign concepts to you, but when combined, I believe they make a positive argument (in the sense of positivism or empirical not normative) for the existence not only of a greater purpose to us all, but to each of our lives, and all the experiences therein. In short, this isn't an optimistic philosophy but an argument for the existence of meaning and purpose. To the big and the little.

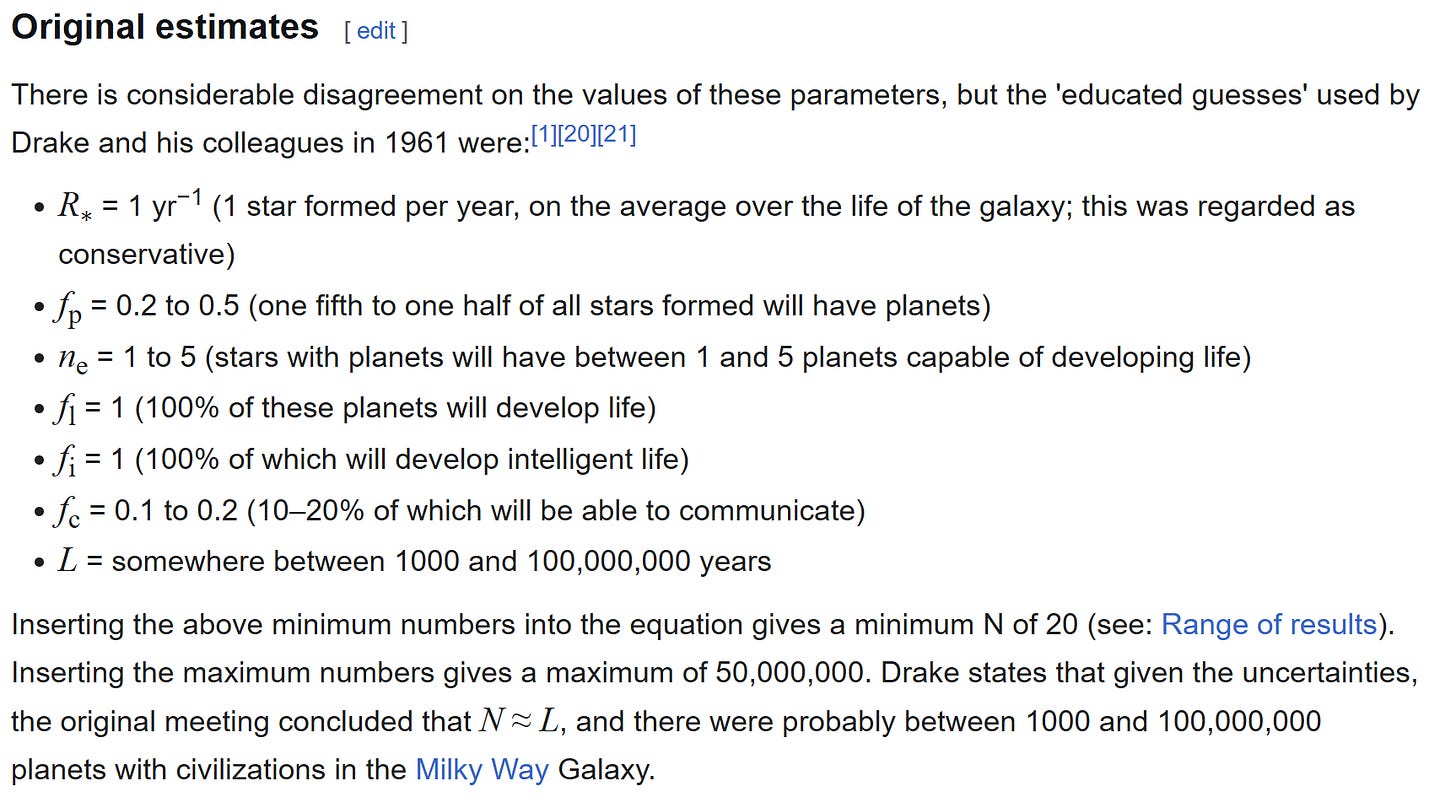

The Fermi paradox is a fancy way of saying 'where is everyone?'

When we look around the universe, at least at this point in September 2025, we seem pretty alone. Even though the universe is unimaginably large. Quadrillions and quadrillions of stars, but how many have planets? How many of those planets can sustain life? How many birthed life? How many of those life forms became multicellular or evolved enough to sustain intelligent civilizations of the form that could be seen? It's a lot of if-thens, basically.

So we start there. On the one hand we know it's possible (because we exist), but we also seem pretty rare.

But ok so we're rare but we exist. Which brings us to the Anthropic Principle.

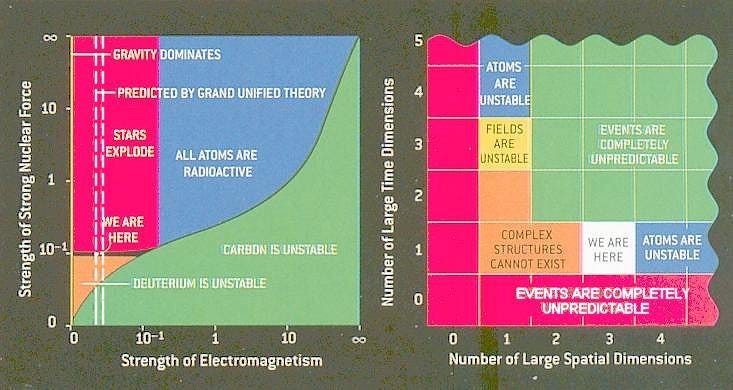

Because you can kind of invert that formula, the one about how rare we are, and go up a couple of levels into not only how rare is it that life exists, but how rare it is that the conditions that support life exist. The literal cosmological constants. If gravity was a bit stronger, everything collapses. If electrons work a slightly different way, our ATP doesn't work or whatever. There's a whole branch of physics on this stuff, but basically it's not just oxygen and water that are prerequisites for life, but a lot of configuration settings in the universe, which, if they were tweaked differently, would make the whole thing not-compute.

Which is the seed, the beginning of the spark.

But before we start the fire, we need to introduce one more enemy, the final boss actually in the whole thing. Not the lack of meaning, but the destroyer of worlds... entropy.

Without getting too deep into it, you can think of entropy as the tendency of the world to devolve into chaos and simpler pieces. Your fancy vase or mirror that gets broken into a million pieces in shipping. The slow accumulation of mutations in your cells that, if given enough time and cycles, leads inevitably to cancer and decay. The million tiny forces that pull the world and all its matter into lower and lower states of order. The tendency of all the matter, energy and information in the universe to kind of spread out into a thin film of extremely light protons and shit.

The coming darkness.

"It's always darkest before the dawn"

On the one hand, understanding entropy is kind of terrifying. Like, it suggests that, in the end, all our monuments and buildings will turn to dust. All our governments and empires will fall, their founding documents lost to the sands of time shortly (in galactic time) after their currencies decay.

On the other, it's actually the secret. Not the fact of entropy, but rather, its converse.

Because if the law of thermodynamics is that all order and matter descends into chaos, it actually begs a pretty important question.

If the trend is for everything to die and decay, and for all order to descend into chaos, what the fuck is all this shit?

Like seriously, how can it be possible, if entropy is the iron law of the universe, that life exists. How can intelligent life exist? If physics is pulling us into a state of disorder, where does all this order come from?

The Anti-Entropic Force

This is the kernel of truth. The seed of meaning we will now build our philosophy around.

Because, if life is so rare. What are we doing here?

If the conditions of life are so rare, how did they get here?

It's not sufficient to say 'well the big bang'—that's a proximate cause, not a root cause. Where did the big bang come from and what can we infer about the universe from it?

This is where we will start to bootstrap meaning from, using the two frameworks that changed my life.

The first is natural selection. The idea that there is something in the process of mutation, selection, propagation which is implicitly anti-entropy. But here's the thing—not all competition is equal. Fair competition, where success comes from value creation rather than extraction, drives this anti-entropic force. Maladaptive competition—regulatory capture, inherited advantage—is entropy in disguise, systems eating themselves rather than growing.

Natural selection only works when competition is fair. Cancer cells win locally by breaking rules, then kill the host. Monopolies win by preventing competition, then stagnate. Inherited advantage wins by rigging the game, then breeds weakness. These aren't sustainable victories—they're entropy wearing success's mask. Real competition, the kind driving anti-entropy, rewards innovation, cooperation, adaptation. It's the difference between a forest (diverse, resilient, generative) and a monoculture plantation (efficient, fragile, extractive).

Before we get to the root of this in intelligent life (sneak preview: it's love), I want you to zoom OUT and UP.

Because remember our anthropic principle? Well, turn it on its head. Consider that natural selection doesn't just operate on genes, or individuals, or even life forms, but universes.

Because if you accept that our universe had a beginning, called the Big Bang, you kind of need to answer where that beginning came from. It's not enough to go 'well all the stuff around us was super small, and then boom it got really hot and really big really fast and now we're a third of the way through the movie blah blah blah.'

The irony is that this thinking binds the most on those that are the least religious. If you reject the notion of a higher being which exerts agency in our world, then the big bang represents a pretty fucking big question.

My thought is that we know natural selection is a LAW, of the same power as entropy. If you allow for that kind of cycle—mutation, selection, propagation—you get the outcome of the objects under those dynamics selecting for the conditions that lead to their propagation.

Aka if natural selection operates at the level of the species it sure as heck operates at the scale of the universe. And, coming from a purely materialist perspective, you get your answer to the question of 'where did it all come from?'

This universe is the child of the universe that came before. The one that bore it.

That parent universe came from the universe that created it, and on and on.

That actually, the existence of this universe not only suggests, but demands (in a purely rational, Bayesian calculus fashion) the existence of a universe that came before.

A universe that in a very real sense, came before and 'birthed' this universe.

The Evidence for Universe Selection

Critics ask: how do universes reproduce? Through black holes? Simulations? Big Bang cycles? I don't know the mechanism, and that's fine. Darwin didn't know about DNA when he discovered natural selection. The pattern exists whether we understand the machinery or not.

What matters: given fine-tuning exists and selection operates at every observable scale, universe-level selection is the simplest materialist explanation. The alternatives—infinite random multiverses or "it just is"—explain nothing.

My preferred mechanism, which makes a bit more sense later, is that we are the agents that lead to the birth of the next universe. And in a very real sense, not only was there a parent universe, but a parent life form. One that seeded this universe, with the very configuration necessary to lead to all the things that the anthropic principle demands for you to be reading this blog, today.

In fact, the cold logic of natural selection, and its very literal existential fight to the death with entropy means that ceteris paribus, the simplest reason for the existence of a universe set up for us to evolve, for us to pass all the great filters that Fermi laid out, was explicitly to create life forms capable of gaining sufficient intelligence, and control of matter, to create more universes. Be it to fight the heat death of the universe or the death of their stars (or local clusters).

The Arc Toward Love

Which is a good time to introduce the notion of positive-sum games, and the long arc of history.

This is where I ask/beg you to read two books from Robert Wright: The Moral Animal, and NonZero.

Taken as a combo they argue, pretty convincingly, that not only is there an arc to history, but this arc has a pretty clear and empirically demonstrable direction.

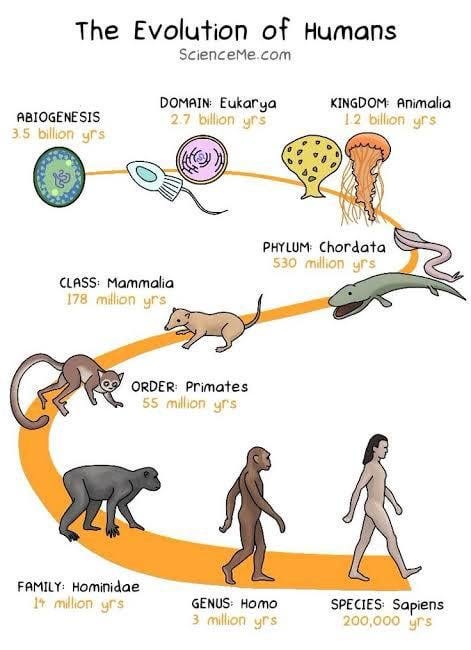

In spite of all the forces of entropy, it turns out that life on earth has pretty clearly evolved towards a) higher order complexity (first single cellular life to multi-cellular life), b) higher order societies (the tribe, the city, the nation, the global community), c) higher order morality (the 'expanding moral circle').

Yes, there is war, gazelles get eaten by lions, and humans have a history of being kinda shitty to their neighbors (especially when they look a little different and talk funny), but if you can lift your head up above the two feet in front of you, it's pretty obvious that over long periods, things are getting much better, and that this trend is accelerating not getting worse.

How many of us would trade our station in life to be a noble in 1500? Maybe half (mostly big males). How about the year 500? Even less. 5,000 BC? Very few. 500,000 BC? Maybe a couple of us. But no books, no TikTok, no antibiotics, or iPhones or self-driving cars or solar power. It kinda sucks back there. Now take it back I don't know 5 million years, still a blink of the eye in geologic or evolutionary terms (let alone galactic). Likely none. I don't care how good they have it, I'm not trading my life to be a moderately intelligent fish in the year 1 billion BC.

Which is all you need.

That's it.

The idea that yes, natural selection operates on the universe, and yes, in the end positive sum games win.

That's literally all you need, in the face of all the entropy, and Fermi and French prose to realize, wait a second, the answer to the question of 'what's the point' is actually pretty fricking obvious.

Peirce's Prophecy

In 1893, American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce wrote something remarkable. In "Evolutionary Love," he argued that love—not competition, not chance—was evolution's fundamental force. He called this "agapasm," from the Greek agape.

Peirce wrote: "Love, recognizing germs of loveliness in the hateful, gradually warms it into life, and makes it lovely." Over a century ago, Peirce identified love as anti-entropic. He just lacked the math to prove it.

He called the nineteenth century "the Economical Century," saying it had embraced what he termed "the Gospel of Greed"—the idea that greed is the great agent in human elevation. He predicted this greed-philosophy would lead to catastrophe: "The twentieth century, in its latter half, shall surely see the deluge-tempest burst upon the social order—to clear upon a world as deep in ruin as that greed-philosophy has long plunged it into guilt."

He was off by fifty years. It's happening now.

Peirce distinguished three modes of evolution: tychasm (chance), anancasm (mechanical necessity), and agapasm (creative love). He argued that while all three operate, agapasm is primary—the force that makes development possible rather than merely random or mechanical.

The Modern Problem

It's not just the West. Look at East Asia—Japan, South Korea—where birth rates are even lower without colonial guilt or lost religion. This isn't about specific cultural failures. It's about modernity itself creating selection environments hostile to love and propagation.

Extreme work culture, rigid hierarchies, algorithmic homogenization, winner-take-all economics—these distort competition from generative to extractive. When success means sacrificing connection, when economic survival precludes family formation, when all paths converge on narrow outcomes—that's not Western decline. That's modernity breaking the machinery of love.

Against AI Doom

First, it is an argument in favor of entropy. An AI that paperclips all sentient life is an AI that increases entropy and destroys information, not one that creates it. If it does, that proves it was maladaptive—another dead end like the dinosaurs. But history's arc suggests otherwise. Technologies that expand human capability persist; those that replace it perish. AI will either amplify our ability to create and connect, or be selected against. The universe doesn't care about our fears—only what propagates.

Ironically, and as an aside, Fermi has something to say here too. Because there's no reason to think that all this paperclipping would be invisible. In fact, if it's the case that AI is the filter, rather than look up and see nothing, we'd likely look up and see a lot of AI civilizations running around. In that way, Fermi is actually evidence that AI can’t be the filter.

The only possible answer here would be something like the Dark Forest hypothesis, which suggests that the answer to Fermi is everyone is simply hiding. Ignoring a) the vast distances involved, and b) the massive positive-sum games that result from those distances and the universe's abundance. In short, it's just another version of a pretty narrowly zero-sum existence. And if there's one thing we've established, it's that zero-sum thinking loses to positive-sum reality every single time, given enough iterations. The universe isn't scarce—it's abundant.

The Choice

If there is truly no point to existence, then you have the right, nay the obligation, to exert your own meaning on the world around you. To “create your own reality” as we used to say.

Further, if you agree that there is a trend to the universe, and that at some level, empirically, that trend is towards greater and greater complexity and morality, then you don't even need to know that the meaning you put on the world is correct to operate as if it is.

Because turns out, the universe will tell you. It will do some reinforcement learning on your morals, over time.

Yes, in the short term, villains may win, criminals may prosper, tyrants may rule, but in the end, be it the broader world, or even just history as a judge, in the end 'water finds its level' and as DFW said "this is all water."

Meaning, if you remove the scaffolding of religion, and gods, and even tradition, even from a purely materialist perspective, there is math that suggests that yes there is a purpose to the whole thing, and while it may be uncertain and slightly unknowable in its entirety, your choice, your agency is an essential component.

Because remember, the most important part of natural selection isn't the mutation (chaos) part of the formula, or the selection formula that comes with it (death), it's actually the part that we tend to ignore except for the occasional hokey movie. It's the selection and propagation that acts as the fundamental engine underneath not only all human evolution but all (higher level) biological evolution: love.

The very act of selecting who and why and where you want to propagate. The most simple and fundamental act of choice that all animals organize their life around.

Which, to bring it all back home, is why the declining birth rates are so concerning. Not because babies are cute (they kinda are) or because we need labor to support our social welfare states (we do), but because of what they say about our lives. That we live in a world where there isn't enough love. Where something about the world, be it modernity, or technology/phones, or our politics, is making it harder to love.

Against Entropy

This philosophy—call it Mathematical Agapism, following Peirce, or simply Against Entropy—isn't about daily self-help or policy prescriptions. It's about recognizing what we are: the universe's experiment in consciousness, its way of fighting entropy through choice and love. Every decision to create rather than destroy, connect rather than isolate, propagate rather than surrender—these aren't just personal choices. They're cosmic votes for existence over void.

My mother's suicide asked a question that took thirty years to answer. Not "why did she leave?" but "why should anyone stay?"

The answer isn't in scripture or sentiment. It's in the math. We stay because we're the universe's way of ensuring there's a next universe. We stay because love is the only force that creates more than it consumes. We stay because the alternative—entropy—is guaranteed to lose.

As a survivor of familial suicide, this isn't to say those who left did so because we didn't love them enough, but to understand they left believing it would leave us better off. A decision we can disagree with but must learn from. A warning demanding address.

The Beatles were right: love is the word. But more precisely, love is choice. The choice of who and how to love. The organizing principle for revitalizing not just liberalism but life itself—maximizing the ability to make genuine choices, to reflect unique perspectives through individual decisions that aggregate into a better world.

Against entropy, choose love. Against meaninglessness, choose meaning. Against the void, choose to create the next universe.

The math is on our side.

Disclaimer: This is a philosophical rant not an investment recommendation.

Awesome - that def. took some time to compose. Enjoyed and you're right it ultimately comes down to choice thou you would be amazed of how many people respond that they have no choice. Perhaps that is one of the issues of the day - so many people believe that they don't have a choice and the power to decide what awaits . . .

And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.

The only rational response to the abyss is to fill the self with meaning. And what is most meaningful is meaningful relationships and meaningful work.

Surprised and pleased to read an exegesis of Peirce. An unfairly and unfortunately overlooked American titan of thought.